Interview

My 30 Years with the Seong Geumyeon School of Gayageum Sanjo

By Jocelyn Clark | Assistant Professor (Ju Sigyeong College of Liberal Arts, East Asian Studies), Pai Chai University

Jocelyn Clark | Assistant Professor (Ju Sigyeong College of Liberal Arts, East Asian Studies), Pai Chai University Jocelyn Clark has spent the last 35 years in and out of Japan, China, and Korea studying music supported by such organizations as the National Gukak Center, the Fulbright Foundation, the Seonam Foundation, the Korea Center at Harvard University, the Korea Foundation, and Taechang Steel's Saya Institute. Jocelyn has a B.A. from Wesleyan University and a Ph. D. from Harvard University in East Asian Languages and Civilizations, including a field in Ethnomusicology. She is also an official jeonsuja under North Jeolla Province Intangible Cultural Property No. 40: Gayageum Sanjo and S. Korean National Intangible Cultural Property No. 23: Gayageum Sanjo and Byeongchang. Currently, she is a professor at Pai Chai University. Photos by Jocelyn Clark, Ryu Ijun, Beondi, Kim Bogyung, Earl Noble, Shuvra Mondal * This article was originally provided in English.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Seong Geumyeon (成錦鳶, 1923- 1983), the founder of the “school” (流派, 유파) of gayageum sanjo that I study. It is also the 30 th anniversary of my arrival in South Korea to begin to learn the gayageum. Most Sundays, I drive 80 km south from Daejeon, where I live and teach at Pai Chai University, to Jeonju’s Hanok Village, where I study sanjo with Seong Geumyeon’s eldest daughter, Ji Seongja (池 成子, 1945-). Seong Geumyeon was born in Korea’s southwest Jeolla region, also the birthplace of sanjo, pansori, and Jeolla-style sinawi. She married the acclaimed multi-instrumentalist and founder of the Gugak orchestra, Ji Yeonghui (池瑛熙, 1909-1980), who grew up just south of Seoul in Gyeonggi Province, an area known for its own musical style, distinct from Seong’s Jeolla style. During her formative years, as she disclosed later in her life, her most influential teacher was An Kiok (安基玉, 1894-1974), a student of Kim Changjo (金昌祖, 1865-1919), the musician usually credited with having started the sanjo genre. When the Korean War broke out in 1950, An moved to North Korea, and, because it was taboo in the South to acknowledge those who went North, Seong did not mention An for many

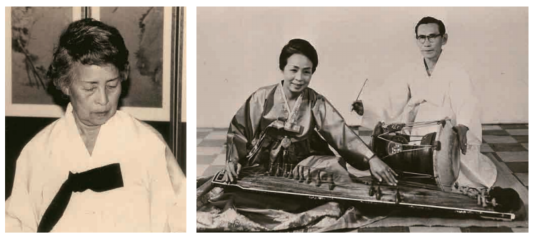

Left Seong Geum’yeon, Important Intangible Cultural Asset for Gayageum Sanjo pictured in Japan in May 1986 at

the Tokyo Korean Culture Center.

Right Seong Geum’yeon with her husband Ji Yeonghui, renowned haegeum player and founder of the first Korean

traditional orchestra and Important Intangible Cultural Asset for sinawi.

years. Before the war she had worked on the jungjungmori rhythmic section of sanjo with PAK Sanggeun (朴相根, 1905-1949), a colleague of her husband’s. She would eventually incorporate a version of this jungjungmori section into her own sanjo and, at times during the years she could not publicly affiliate herself with An, would name Pak as her teacher when asked. During and after the war years, Seong developed her own sanjo in earnest, always accompanied by her husband Ji Yeonghi, and, in 1968, she was designated one of the two first “Important Intangible Cultural Assets” for gayageum sanjo. Seong’s sanjo, one of the most popular of her day, has been described as having “sorrowful but not excessive feminine beauty,” incorporating the “lightness and sophisticated metaphor” of her husband’s Gyeonggi Province sound (“gyeongtori”). Her short sanjo, first created for short-format broadcast, were considered foundational and eventually incorporated into most South Korean music textbooks, thus becoming part of every gayageum student’s repertoire. This was my personal entry into the Seong Geumyeon School back in 1992. Seong performed in the first Korean concert at Carnegie Hall in 1972, along with her husband Ji Yeonghui, pansori singer Kim Sohee (金素姬, 1917-1995), and fellow class of 1968 gayageum sanjo “national treasure” Kim Yundeok (金允德, 1918-1978). Up until her death in 1983, Seong continued to refine her sanjo with the help of her daughters, most prominently my teacher, Ji Seongja. To this day, Ji continues to perform her mother’s 72-minute sanjo, and this is the sanjo she is transmitting to her daughter, Kim Bokyung, her granddaughters, and her students, including me.

What is Sanjo?

Descended from sinawi and pansori (solo story-singing), sanjo remains at the heart of the repertoire for Korean solo instrumental music (“solo” here includes drum accompaniment, usually on a janggu (hourglass-shaped drum) and sometimes on a sori buk (barrel drum)). Sanjo was developed on stringed instruments, starting with the gayageum, followed by geomungo, and then by the “wind” instruments daegeum, and haegeum (which passes for a wind instrument at times) in the late 19th century, and, in the 1950s, by the bowed zither, the ajaeng. All are expressive instruments capable of producing large bends and wide vibrato.

Ji Seongja, daughter of Seong Geum’yeon. Current Important Intangible Cultural Asset for Gayageum Sanjo for North Jeolla Province.

Sanjo has a specific “movement” structure based on a progression of rhythmic cycles, called jangdan (長短, lit. “long and short”), which gradually increase in density and pulse as the sanjo progresses. Melodic modes called jo express various emotional aesthetics, including ujo (羽調, strength), pyeongjo (平調, peace), and gyemyeonjo (界面調, sorrow), among others. Sanjo has been designated National Important Intangible Cultural Heritage numbers 16, 23, and 45, each associated with a different instrument: geomungo sanjo, gayageum sanjo, and daegeum sanjo, respectively. It also appears in regional, provincial, and city lists of intangible heritage. In Korea, sanjo remains a prerequisite for all instrumental majors in high school and college. Today, many younger musicians have started composing their own “schools” of sanjo, based on their teachers’ melodies or sometimes simply composed from scratch, including on instruments traditionally considered ill-suited for sanjo due to their lack of ability to bend notes or produce the wide vibrato that gives the genre its emotional range. These innovations are affecting how the public views sanjo and its aesthetics in the 21st century.

From Folk Music to Art Music

When I first started studying Korean music, sanjo was listed as “folk music,” as distinct from “court” or “aristocratic” music—translated literally, “correct” music (jeong’ak, 正樂). Early in my studies, I learned that Korean court musicians had coined the somewhat pejorative term hoteun garak, meaning “scattered melodies,” to describe the improvisational “scattered”-sounding solo music coming out of the southwest provinces. Eventually, sanjo would be ascribed its Sino-Korean characters (散調) as it became an established genre.

Jocelyn Clark introducing the gayageum to Korean elementary students in Daejeon.

A few years ago, my teacher’s daughter, Kim Bokyung, gave a special lecture on Korean music genres to my university class in which she referred to sanjo as “art music.” I was surprised and interested to find out how what I had been taught was “folk music” had become “art music.” Wikipedia defines “art music” as “classical,” “cultivated,” “serious,” “canonic” music— music considered to be of high phono-aesthetic value. The term typically implies advanced structural and theoretical considerations and is often associated with written musical traditions. In this context, the terms “serious” or “cultivated” are frequently used to distinguish a form from ordinary, everyday music. My teacher, Ji Seongja, currently North Jeolla Province Important Human Cultural Asset No. 40 for Gayageum Sanjo, traces the emergence of the term “art music,” which she has come to embrace, to the founding of the Cultural Asset System. As designated lineage holders in this system, today’s masters are expected to transmit their compositions in perpetuity. So, while someone’s sanjo may start off as truly improvised “scattered melodies,” once it is designated a protected “school” within the system, the more patterned and distilled it becomes through organization and repetitive teaching. Taking Seong Geumyeon’s own work as a case in point, we see how her daughter(s) collected all the different bits and pieces she composed over her lifetime and began to fit them together in a certain order, dropping some melodies and adding new connectors, until the sanjo went from 30 minutes to over 70. This is the moment in sanjo’s history where I came onto the scene. Ji has been teaching me her 70+minute sanjo for many years now, and I still have 15 minutes of it I have not yet even begun to practice.

The External Cultural Environment and The Internal Life of the Foreign Student

Up through the first half of the 21st century, ethnomusicologists globally exhibited strong interest in sanjo, with some writing about it in English. Then the Korean Wave washed sanjo up the beach and hid it in the tall cultural grass of popular music, where it would be further buried under K-pop’s driftwood. Largely as a result of the international success of the country’s popular genres, over the past few decades a series of social, aesthetic, and legal shifts have occurred in Korean society that have altered the chemistry and volume of the “traditional” waters in which sanjo once swam. Musical meaning is normally derived from the ways in which pieces, genres, and performances relate to both physical landscape (e.g., urban vs. rural) and musical landscape (e.g., other pieces, genres, performances, and audiences). Here in 21st- century South Korea, both landscapes have changed and continue to change dramatically. Amid these environmental shifts, I too have changed. After 30 years, I am finally starting to feel the weight of each note and hear the minute details of ornament and rhythm that punctuate sanjo’s melodic and rhythmic modes. This heightened awareness is not only affecting how I play and how I feel when I am playing, but I find myself thinking about, and writing about, sanjo’s history, musical elements, and meaning in a much more nuanced way. Only now am I beginning to internalize on a deep level what my teachers have been saying to me all these years. It takes a long time to get rid of one’s “Western music accent.” An accent is often something we cannot recognize in ourselves. If we could, and we knew how, we might try to fix it on our own. Thankfully, in this regard, I have excellent guidance. While, in the case of gayageum sanjo, my Western music accent lives in the muscles of my fingers and lingers in my ear, it does so less and less prominently as time goes on. A long road remains before me, but from my current vantage I am beginning to see the way ahead more clearly.

Jocelyn Clark performing sanjo in Jeonju.