Inside

Korean Documentary Heritage Enters the Global Memory

By the World Heritage Team

The two World Wars caused damage in diverse forms and of varying severity to documentary heritage across the globe. Korea was not excluded. As part of the efforts to preserve the surviving documentary heritage, the Korean government is participating in UNESCO’s Memory of the World program by listing the country’s documents on this register. Late last year, three more items of Korean documentary heritage were inscribed on the Memory of the World register, expanding the number of Korean entries to sixteen, the highest in the Asia and Pacific region and the fourth in the world. Below, the significance of the three Memory of the World entries that have become part of this record of global meaning are explored.

Documents on Joseon’s Diplomatic Missions to Japan

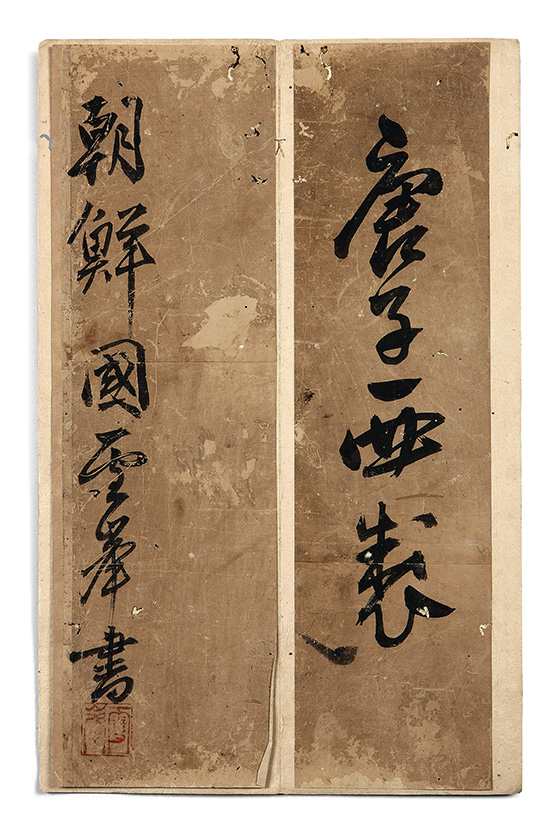

A calligraphic artwork by the 17th-century literary official Kim Ui-sin, currently housed in Japan

Shrouded in mystery and sanctity, Geumgangsan has long topped Koreans’ travel wish lists. Geumgangsan, or the “Diamond Mountains,” offers both spectacular mountain landscapes and stunning ocean panoramas along the east coast of the Korean Peninsula. The gorgeous mountain scenery has served as a major source of artistic inspiration since beyond the limits of time. Geumgangsan held a central position as a motif for “true-view” (jingyeong) landscape painting, an artistic style that came into vogue toward the later Joseon period (1392–1910). The area was also depicted by court painters of the era. While not used for decorative purposes, royal paintings of Geumgangsan shared much in common with royal decorative paintings on such themes as five peaks with a sun and a moon (irwolobongdo), ten symbols of longevity, peony blossoms, and flowers and birds. This was especially true in terms of the use of deep colors, stylized expressions, and adoption of mysterious symbols.

In this regard, the two Geumgangsan paintings decorating the walls of Huijeongdang Hall in Changdeok -gung Palace are quite unique: they differ not only from traditional Geumgangsan paintings, but also from other royal paintings intended for decoration. They are known as Chongseokjeong jeolgyeongdo (Superb Landscape of Chongseokjeong Pavilion) and Geumgangsan manmulcho seunggyeongdo (Picturesque Landscape of the Myriad Things on Geumgangsan Mountain) and were created by the early modern painter and calligrapher Kim Gyu-jin (1868–1933). Each of the two paintings shows the remarkable scenery of Geumgangsan on an 884-by-195-centimeter surface made from seven pieces of connected silk cloth.

A Comprehensive Collection of Royal Seals and Books from Joseon

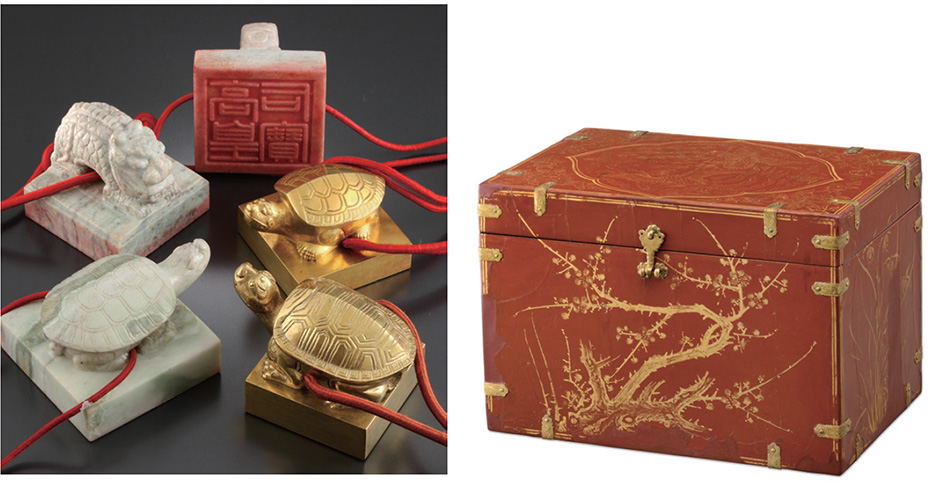

Left_Ceremonial seals created for an investiture or the offering of honorary titles, Right_A container for a jade book

Another item recognized by the Memory of the World is a collection of royal seals and books from the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). Throughout the Joseon era, royal seals and ceremonial books were crafted for the heirs or holders of the throne and their spouses on such occasions as investiture, enthronement, and the endowment of honorary titles. These ceremonial objects represented the legitimacy and sovereignty of the dynasty. The surviving royal seals and books serve as a carrier of this symbolism for the Republic of Korea, the political successor to the Joseon Dynasty.

The inscribed seals and books, respectively inscribed with the title to be bestowed on the seal bearer and featuring annotations on the meaning of the title, come in diverse materials pertaining to the position of the bearer. Seals for kings and queens were made of gold or jade, and distinctively known as bo, or “treasures.” For crown princes and their spouses, seals of silver or jade addressed as in, or “stamps,” were provided. As for royal books, jade was used for kings and queens, and bamboo was reserved for crown princes and princesses. These royal seals and books conferred on a king served as a signifier of his authority as the legitimate successor of the dynastic rule during his lifetime and after his death, and came to possess divine meaning to serve as sacred objects unto themselves.

The practice of offering ceremonial seals and books to sovereign members of the royal family continued throughout the dynastic period for about 570 years from the dynastic founder Taejo to the final monarch, King Sungjong. This enduring tradition of producing ceremonial seals and books for royal members has no parallel in other countries within the overall cultural sphere, including China, Japan, and Vietnam. There are cases in China and Vietnam of the creation of these ceremonial objects, but only for a scattered selection of royal family members. The inscribed seals and books from the Joseon Dynasty make up a rare collection of royal objects that spans the entire period of dynastic rule. The inscribed heritage consists of 669 royal objects in five categories: 331 seals, thirty-two edicts in silk, 258 jade books, forty-one bamboo books, and seven gold books. The 338 ceremonial books, which were composed by the leading practitioners and calligraphers of the given time, feature an immense number of Chinese characters (128,618).

The royal seals and ceremonial books of the Joseon Dynasty offered sovereign legitimacy to kings while on the throne and unquestioned sanctity after death, contributing greatly to the political stability of their rule. This unique cultural phenomenon is eloquently testified to by the inscribed heritage, granting it sufficient significance for the Memory of the World.

Archives of the Nationwide Debt Repayment Campaign

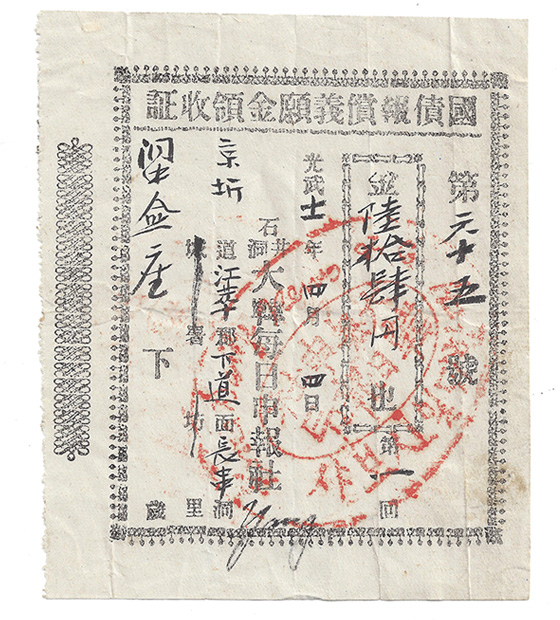

A receipt for a donation to the National Debt Redemption Movement

Also inscribed were the archives on the National Debt Redemption Movement, a voluntary public campaign conducted from 1907 to 1910 to repay the sovereign debts owed to Japan.

In the early 20th century, Japan imposed massive loans of thirteen million KRW on Korea as a means to strengthen colonial control over its protectorate. Unable to repay this enormous debt, nearly equivalent to the country’s annual budget, the Korean government stood at risk of national default. Facing this national crisis, the country rose to the challenge. Campaigns to pay back this sovereign debt voluntarily emerged across the territory. People from all walks of life, of both genders, and all ages donated: men by cutting back on smoking and drinking, women by selling their jewelry, people with no other financial means by making straw shoes, studvents by saving their allowances, and children by running errands. Normally less-active social groups, such as female entertainers (gisaeng), beggars, and thieves, participated as well. It was an energetic exercise of civic responsibility that took place nationwide under the lofty cause of repaying the national debt.

Media coverage of the national campaign was extensive, particularly over the participation of female members of society. Newspaper and magazine articles from the time noted surprise at the level of participation by women in general, and in particular by female entertainers and widows. They reported that the debt redemption movement started as a non-smoking campaign spearheaded by men, but within a few days came to involve women when a group in Daegu began a drive eliciting donations from women.

In this regard, the National Debt Redemption Movement epitomizes the spirit of civic responsibility that was voluntarily mobilized in the face of a national crisis. It is also an example of the first media campaign to take place in Korea. It is this unique combination of civic participation and active journalism under the cause of national debt repayment that provides the significance of the National Debt Redemption Movement. Since the National Debt Redemption Movement was a powerful civil campaign involving as much as around 25 percent of the population and also served as a model for similar campaigns in the former colonies of imperial powers, the nominated heritage chronicling the full process of the movement from diverse perspectives was inscribed on the Memory of the World register.

These three items of Korean documentary heritage inscribed in 2017 join the previous thirteen: Hunmin jeongeum (1997), The Annals of the Joseon Dynasty (1997), the Second Volume of “Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests’ Zen Teachings” (2001), Seungjeongwon ilgi (2001), Uigwe (2007), Painting Woodblocks for the Tripitaka Koreana and Miscellaneous Buddhist Scriptures (2007), Donguibogam (2009), Ilseongnok (2011), Archives for the May 18th Democratic Uprising against the Military Regime in Gwangju (2011), Nanjung ilgi (2013), Archives of Saemaul Undong (2013), Confucian Printing Woodblocks (2015), and Archives of the KBS Special Live Broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families” (2015). With these sixteen items listed on this global record, efforts will continue to identify further documentary heritage of global significance and disseminate its value through the Memory of the World program.

Text by the World Heritage Team, Cultural Heritage Administration

「조선통신사 기록물」「조선왕실 어보와 어책」「국채보상운동 기록물」

세계가 인정하는 기록 되다

인류가 두 차례의 세계 대전의 참화를 겪으며 전 세계의 중요한 기록물은 다양한 어려움을 겪어왔다. 대한민국도 예외는 아니라서 보존을 위해 중요한 기록물은 세계기록유산으로 등재하기 위해 노력을 아끼지 않았다. 지난해 「조선통신사 기록물」, 「조선왕실 어보(御寶)와 어책(御冊)」, 「국채보상운동 기록물」이 동시 등재되면서 한국의 세계기록유산은 총 16건이 되었다. 이는 세계에서 네 번째, 아태지역에서는 첫 번째로 많다. 인류가 기억해야 할 유산으로 새롭게 등재된 세 건의 기록물이 지닌 의미와 가치를 살펴보자.

조선통신사 기록, 양국의 성공적인 공동 등재

먼저 조선통신사 기록에 대해 살펴보면, 1607년부터 1811년까지, 일본 에도막부의 초청으로 12회에 걸쳐, 조선국에서 일본국으로 파견되었던 외교사절단에 관한 자료를 말한다. 조선통신사에 관한 기록물은 양국의 정부 및 지역의 행정기관ㆍ박물관 혹은 대학 등에 보존되어 왔다. 세계기록유산 등재추진 주체는 한국의 재단 법인 부산문화재단과 일본의 NPO법인 조선통신사연지(緣地)연락협의회이다. 두 단체는 조선통신사의 역사적·세계적 의의를 더욱 널리 확산하기 위해 유네스코 기록유산으로 등재할 필요가 있다는데 인식을 같이해왔다. 이에 두 나라에서 각각 추진위원회를 발족하고, 산하에 학술위원회를 구성하여 조선통신사에 관한 기록의 조사ㆍ정리 및 연구와 토론을 진행하였다. 조선통신사가 추구한 평화 교류의 의의를 널리 알리려는 목적에서 공동 등재 신청의 주체가 된 것이다. 이는 양국이 힘을 합쳐 성공한 첫 사례로 그 의미가 더욱 뜻 깊게 다가온다.

조선통신사는 16세기 말 일본에서 조선을 침략한 이후 단절된 국교를 회복하고, 양국의 평화적인 관계구축 및 유지에 크게 공헌했다. 조선통신사가 왕래했던 17~19세기에는 유럽의 여러 나라가 전쟁을 반복하여 침략과 정복을 동반한 폭력적인 지배를 확대했다. 당시, 동아시아에서 가장 명확하게 평화적 교류를 목적으로 두 나라가 교류를 전개한 사례가 조선과 일본 간을 왕래한 조선통신사다. 조선통신사에 관한 기록은 세계역사상 전쟁과 폭력이 횡행하던 시대에 외교를 통해 평화구축과 상호이해를 촉진시킨 귀중한 유산이라고 할 수 있다. 조선통신사에 관한 기록은 오랜 기간 평화체제 구축을 목적으로 행하여진 외교적 실천의 결과물이라는 점에서 세계적인 중요성을 가지고 있다. 이 점에서 조선통신사에 관한 기록은 17세기~19세기의 동아시아뿐만이 아니라, 오늘날에 있어서도 전쟁과 갈등을 뛰어넘어 인류의 평화적인 공존을 추구하기 위한 모범적인 교과서라고 할 수 있다.

외교기록은 조선과 일본의 국가기관에서 작성된 공식기록과 외교문서로, 조선통신사 파견과 관련된 전반적인 내용을 포함하는 통신사등록 등 조선왕조가 편찬한 기록, 조선국왕이 일본의 에도 막부의 장군에게 보낸 조선국서 등이 포함된다. 문서에는 양국 통치자가 선린우호를 구축하고 그것이 지속되기를 바라는 의사가 반영되어 있으며, 더불어 통신(通信)의 원칙과 방법이 빠짐없이 기재되어 있다. 여정의 기록은 조선의 수도인 한양(서울)에서 일본의 에도(도쿄)까지 왕복 4,500km에 달하는 대장정의 노정에서 생긴 일들을 적었다. 또한 견문에 대해 언론 담당인 삼사 및 외교 사절인 사행원이 구체적으로 기록한 통신사행록, 일본 각지의 응접 책임자가 기록한 향응기록, 그리고 노정 곳곳에서 사행의 행렬과 현지의 풍경을 생생하게 그린 기록화와 감상화 등을 포함한다. 문화교류의 기록은 조선통신사의 왕래로 다양한 분야에서 활발한 교류가 이루어지면서 대량으로 제작된 필담창화집, 시문, 서화를 말한다.

이렇듯 조선통신사의 왕래로 두 나라의 국민은 증오와 오해를 풀고 상호이해를 넓혀 외교뿐만 아니라 학술, 예술, 산업, 문화 등의 다양한 분야에서 활발한 교류의 성과를 낼 수 있었다. 또한 조선통신사에 관한 기록은 조선통신사의 모든 외교, 여정, 문화교류가 담겨있는 종합기록으로서 12차례나 되는 외교사절을 한 차례도 소홀함이 없이 완전하게 기록되었기 때문에 세계기록유산으로서 가치를 인정받았다.

정통성을 상징하는 어보, 신성성을 부여하는 어책

어보와 어책은 조선왕조의 영속성을 상징하고 국가의 번창을 기원하기 위해 만들어졌다. 현재 남아있는 어보의 의미는 대한민국의 정통성을 주장할 수 있는 국가의 상징적이고 신성한 기물로서의 위상을 차지하고 있다.

금·은·옥·죽(대나무)·오색 비단 등에 글씨를 쓰거나 새긴 어보와 어책은 기록유산으로서의 다양한 형태를 보여주고 있다. 어보의 경우 왕과 왕비는 금이나 옥으로 만든 보(寶)를 받고, 세자와 세자빈은 은이나 옥으로 만든 인(印)를 받았다. 어책의 경우에도 왕과 왕비는 옥, 세자와 세자빈은 죽(대나무)에 글자를 새겨 구분하였다. 생전에는 주로 정통성을 표출하였지만, 죽은 뒤에는 죽은 자의 권위를 보장하고 여기에 신성성이 가미되어 어보와 어책 자체가 신물(神物)로서의 상징성을 부여하였다.

어보와 어책은 조선을 개국한 태조부터 마지막 황태자인 순종까지 왕과 왕비, 세자와 세자빈을 비롯하여 후궁까지 포함하여 570여 년 동안 지속적으로 제작․봉헌되었으며, 조선왕실 컬렉션의 성격을 띠고 있다. 이러한 컬렉션은 중국과 베트남, 일본 등의 문화권에도 그 예를 찾을 수 없다. 중국과 베트남에서는 간혹 한 두 사람의 어보와 어책은 존재했지만, 왕실 또는 황실 구성원 전체의 컬렉션은 조선왕실만이 갖고 있어 희귀성이 지대하다.

어보의 보문을 제외한 어책에 수록된 글은 대제학(大提學)을 비롯한 당대의 최고 문장가가 짓고, 글씨는 최고의 명필이 서사관으로 참여해 썼다. 이렇게 작성된 분량은 매우 방대하여 4종 334점에 이른다. 어책에 적힌 글자 숫자만 해도 교명문이 32점에 9,062자, 옥책문이 258점에 105,286자, 죽책문이 41점에 12,984자, 금책문이 7점에 1,286자로 모두 338건 128,618자가 수록되어 있다.

왕조의 영원한 지속성을 상징하는 어보와 그것을 주석(annotation)한 어책은 현재의 왕에게는 정통성을, 사후에는 권위를 보장하는 신성성을 부여함으로서 성물(聖物)로 숭배되었다. 이런 면에서 볼 때 책보는 왕실의 정치적 안정성을 확립하는데 크게 기여하였음을 알 수 있다. 이것은 인류문화사에서 볼 때 매우 독특한(unique) 문화양상을 표출하였다는 점에서 그 가치가 매우 높은 기록문화 유산이라 할 수 있다.

대한민국 최초의 언론캠페인 국채보상운동

국채보상운동 기록물은 국가가 진 빚을 국민이 갚기 위해 한국에서 1907년부터 1910년까지 일어난 국채보상운동의 전 과정을 보여주는 기록물이다.

20세기 초, 일본이 한국에 대한 식민지화 정책의 일환으로 국가 1년 예산에 맞먹는 1,300만 원이라는 거액의 차관을 강제로 제공했다. 그러나 한국 정부는 이 외채와 고리대를 갚을 수 없게 됨으로 외채로 인한 망국의 위기에 빠지게 되었다. 이때 전국적 외채 갚기 운동이 자발적으로 일어났다. 남성은 술과 담배를 끊은 돈으로, 여성은 반지와 비녀 등 패물로, 가난한 서민들은 짚신을 삼고 나무를 해서 판 돈으로, 학생은 용돈으로, 아이는 심부름 돈으로 이 운동에 참여했으며, 기생과 걸인, 심지어 도적까지도 의연금을 내는 등 전 국민이 국채보상운동에 적극적으로 참여하였다. 따라서 당시 한국 사람들은 전국적 기부운동을 통해 국가가 진 외채를 갚음으로써 그 국민으로서의 책임을 다 하려 하였다.

특히 언론 기록물은 여성참여를 매우 적극적으로 보도했다. 여성 중에도 특히 기생, 과부의 참여가 많았음을 기록하고 있다. 국채보상운동이 남성중심의 금연운동으로 시작되었지만, 이 운동이 시작된 지 이틀 만에 대구지역 여성이 ‘나라 사랑에는 남녀 구분이 없다’고 선언하면서 단체를 결성하여 자신이 몸에 지니고 있던 패물을 기부하는 등의 여성단체 기부운동을 시작하였음을 보도하고 있다.

이런 점에서 한국의 국채보상운동 기록물은 국가적 위기에 자발적으로 대응하는 시민적 「책임」의 진면목을 보여주는 역사적 기록물이다. 뿐만 아니라 국채보상운동 언론캠페인은 한국 최초의 언론캠페인일 뿐만 아니라 악성 외채를 갚기 위해 공동체적 기부운동과 저널리즘이 결합한 사례는 세계적으로 유례가 없다. 전 국민의 약 25%가 외채를 갚아 국민으로서 책임을 다하려 한 국민적 기부운동이었다는 점과 이후 제국주의 침략을 받은 여러 국가에서 유사한 방식으로 국채보상운동이 연이어 일어난 점 등으로 세계적 중요성을 인정받았다.

Text by 세계유산팀