Feature

Gojong, a Misfortunate Monarch

By Kim Jae-eun

In the context of the lengthy history of Korea, the early-modern period of about thirty years from the opening of ports in 1876 to the forceful annexation by Japan in 1910 represents just a split-second. However, this brief period holds disproportionate significance since it shifted the historical course of the country toward modernization. This did not mean simply replacing oil lamps with electric lights or traditional costumes with Western suits: it was a make-or-break effort in a desperate pursuit of national independence in the face of a rapidly shifting international order. The last king of the Joseon Dynasty and the first ruler of the Korean Empire, Emperor Gojong was at the forefront of this momentous endeavor, experiencing first-hand the brunt of the era’s historical turbulence.

Opening to the West

A portrait of Gojong wearing yellow, a color reserved for emperor.

Photo courtesy of the Natinal Museum of Korea

Pitched into the international diplomatic system upon the signing of the Treaty of Ganghwa with Japan in 1876, Joseon concluded its first agreement with a Western state in 1882 prosperity with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States. This commercial understanding was forged at a time when Confucian perceptions still dominated the Korean consciousness and Westerners were treated as “barbarians.” It was a strong show of the staunch commitment of the Joseon court to seek opportunities for national prosperity through the introduction of advanced material culture from the West.

Gojong’s unwavering belief in the benefits of modernization found expression in a royal message released after the Military Mutiny of 1882. In this communication, the Joseon monarch called attention to the shifting global order in which the West was taking the lead in advancing material culture and to the superb capability of their technology and machinery. He admired how Western states were conducting active exchanges in products and techniques and then feeding the results into economic growth and military might. Gojong stressed that it was only natural for Joseon to step back from its isolationist ways and open itself to the fruits of Western material development for the sake of national prosperity. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the United States speaks volumes about the survival strategy that Gojong and his court pursued in the face of the emerging world order.

With the completion of the treaty in 1882, the United States dispatched a minister and installed an American legation in Seoul. The Joseon court allowed the entrance of American soldiers, teachers, and missionaries into Korean territory, and issued permits for their educational and medical programs. These American residents played a critical role in introducing Western culture and products into Joseon society. In return for the dispatch of a minister from the United States, Gojong authorized a friendly mission led by Min Yeong-ik. Once in the United States, the Joseon embassy had an audience with then-U.S. President Chester Arthur. They spent roughly forty days touring a range of modern institutions, including trade fairs, textile factories, farms, newspapers, fire stations, and post offices. Upon their return to Joseon, their experiences provided a foundation for government modernization enterprises.

Ascending to Emperor Status

A robe with an embroidered dragon for the emperor.Photo courtesy of Sejong University Museum

The modernization programs initiated by Gojong and his government were not universally successful. Many of them floundered in the face of powerful resistance from internal conservative forces or upon obstruction stemming from the fierce rivalry over the Korean Peninsula among imperialist powers. Joseon found itself in a catch-22 where it required social modernization as a precursor for national independence but it could not push ahead with modernization programs without the sovereign rights of an independent country. After weathering a series of unsettling events—the Coup of 1884, the Uprising of the Donghak Peasant Army in 1894, and the Sino-Japanese War in 1894–5—Gojong inaugurated the “Great Han Empire,” or the Korean Empire, in 1897. He assumed emperor status in an attempt to provide a turning point in the historical impasse in which he found himself.

The cover of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Joseon and

the United States that laid a foundation for Korean modernization.

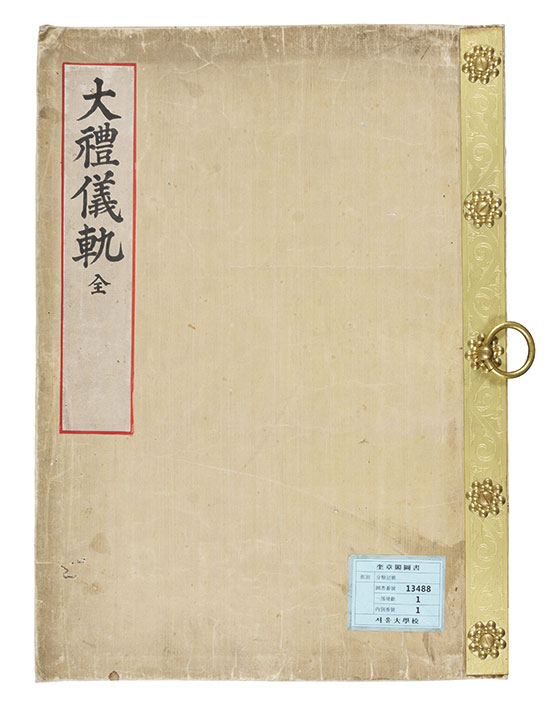

The cover of The Protocols of the Enthronement of Gojong (Gojong daerye uigwe),

a compilation on the process of Gojong ascending to emperor status

Behind Gojong’s decision to promote himself to emperor was a strong need for Joseon to place itself on an equal footing with Qing China, which had long claimed suzerainty over the Korean Peninsula. This was a precursor for securing international recognition as an independent state. Ritual preparations for the imperial inauguration and the enthronement ceremony are recorded in detail in The Protocols of the Enthronement of Gojong (Gojong daerye uigwe). During the ceremony, traditional symbols generally reserved for Chinese emperors, such as the color yellow and dragon motifs, were actively adopted as a means to highlight the elevation of the Korean ruler. A pictorial description in the Protocols shows a golden palanquin carrying the emperor’s seal amid an imperial procession to the Altar of Heaven (Hwangudan), where Gojong’s enthronement as emperor was announced to the heavens. Wearing a yellow robe and seated in a gold-colored chair decorated with dragon designs, Gojong was granted at the Altar of Heaven an imperial seal with a dragon-shaped handle. The Protocols provides a detailed explanation and description of these ritual objects symbolizing the emperor’s authority.

Economy and Military Development

Gojong wearing a military costume

as the Commander in Chief. Gojong established

the Wonsubu (Supreme Military Council)

and became the leader of the military as a means to

strengthen its power.

Photo courtesy of the National Palace Museum of Korea

Once on the imperial throne, Gojong redoubled his quest for economic prosperity and military strength. In the years surrounding the inauguration of the Korean Empire, the material condition of Seoul was transformed with the refurbishment of road networks, installation of electric lighting and telephone service, and operation of streetcars. A railway from Seoul to Kaesong was laid in 1902. Major infrastructure facilities, such as a mint, printing office, office for the standards of weights and measures, sericulture office, and the Hanseong Electric Company, were all instituted under the Council of the Royal Household so that they could benefit from government support. A bank, one of the most fundamental institutions for industrial development, was established as well.

Along with this industrial stimulus, decisive measures for strengthening the national defense were carried out. Emperor Gojong instituted the Wonsubu (Supreme Military Council) as the highest military authority and invested himself as its Commander in Chief. This clearly signaled his adamant commitment to restoring military power. A photo from the time presents Gojong in a military uniform and helmet modeled after those worn in Japan, France, and Prussia, conveying the emperor’s dedicated efforts to safeguard Korean autonomy.

A Last-ditch Effort for the Future

The seal Emperor Gojong used for clandestine diplomatic activities. It is rendered in a surreptitious size 5.2 centimeters wide, 6.6 centimeters long, and 4.9 centimeters high. Photo courtesy of the National Palace Museum of Korea

The strenuous efforts of Emperor Gojong and his court to salvage sovereignty fell short of saving the country from its waning historical fortunes. Claiming a dominant interest in the Korean Peninsula after victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904, Japan forced a series of treaties on Korea —the Japan-Korea Protocol of 1904, the Protectorate Treaty in 1905 and the Treaty of 1907—that gradually encroached upon its autonomy. Even after the diplomatic discretion allowed the Joseon ruler was severely limited by the Protectorate Treaty, Emperor Gojong did not abandon himself to his fate. He dispatched a secret mission to the Second Hague Peace Conference in the Netherlands in an attempt to appeal to the international community against Japanese aggression and enlist their support in restoring Korean sovereignty.

A special seal inscribed with four Chinese characters meaning “Seal of the Emperor” (nationally designated as Treasure No. 1618) was used by the emperor for his clandestine diplomatic activities. This stamp is not recorded in The Totality of Seals and Marks (Boin busin chongsu), an illustrated compilation of the stamps and administrative tokens used during the Korean Empire period. Gojong kept this seal out of the official management system and used it secretly for clandestine diplomacy. Rendered smaller than is considered normal for a royal seal, this imperial stamp must have been handy to keep stashed away. Although the diplomatic enterprises the seal was dedicated to did not succeed, it provides eloquent testimony on Gojong’s desperate efforts to protect the sovereignty of his country up until the final moments of his imperial rule.

In the travel journals and geographies compiled by Westerners following the opening of Korean ports, the country was predominantly described as the Land of Morning Calm. This representation of Korea, widely diffused in the West, denotes the rustic and peaceful atmosphere of the country. On the flip-side of this peaceful image, however, was an imperialistic gaze that perceived Joseon as passive and incapable, and therefore justified its absorption. Gojong may have come across as an incompetent and powerless monarch who could not devise an appropriate response to the threat to his sovereign rights. However, the anecdotes and objects associated with Gojong and his rule that have been briefly related above tell a somewhat different story. The early-modern period in Korea was neither peaceful nor calm. Emperor Gojong was caught in a whirlwind of tumultuous events and did his utmost untipl the very last moment to save his country from the forces of history.

Text by Kim Jae-eun, Deoksugung Management Office

Photos by the Kyujanggak Institute for Korean Studies at Seoul National University, Sejong University Museum, National Museum of Korea, and National Palace Museum of Korea

고종. 격동의 시대, 비운의 군주

한국의 유구한 역사 가운데 개항 이후부터 한일 강제 병합까지는 아주 짧은 시기에 불과하지만, 한국 사회가 근대사회로의 전환을 이루는 첫머리에 위치하였다는 점에서 그 무게감은 결코 가볍지 않다. 이 시기 서구 문물의 수용을 통한 근대화를 위한 노력은 단순히 호롱불 대신 전깃불을 사용하고, 한복 대신 양복을 착용하는 변화를 넘어 제국주의가 지배하는 세계질서 속에서 한국이 과연 독립국가로 존속할 수 있을 것인지를 가늠하는 절체절명의 선택이기도 하였다. 조선의 마지막 왕이자, 대한제국의 초대 황제였던 고종은 이와 같은 시기를 가장 첨예하게 겪어내고 있던 사람이었다고 할 수 있을 것이다.

서구에 문을 열다

1876년 일본과 수호 조규를 체결함에 따라 근대적인 외교 질서에 편입된 조선은, 1882년 서양 국가 중 최초로 미국과 조약을 체결하였다. 유교적인 세계관 속에서 서양을 야만으로 간주하는 인식이 팽배했던 속에서도 서구의 발전한 문물을 받아들여 나라의 부강을 추구한다는 방침을 명확히 한 것이었다.

서구 문물 수용에 대한 고종의 인식은 임오군란(1882) 이후 발표한 윤음(綸音)에서 명확하게 드러난다. 고종은 서구가 물질문명의 발전을 선도해 가고 있었던 세계정세의 변화를 직시하였다. 서구의 여러 나라가 가지고 있는 기술과 기계의 우수성에 주목하면서, 이들이 정교하고 이로운 여러 기계를 바탕으로 나라를 부강하게 하고 서로 교류하는 모습은 과거 유교적 지식인들이 이상적으로 여겼던 춘추시대를 방불케 한다고까지 했다. 따라서 조선 또한 고립되어 살아갈 수 없으며, 그들의 발전된 문물을 받아들여 부강하도록 하는 것은 당연한 것이라고 했다. 미국과 맺은 이 조약은 세계 질서 속에서 조선 정부와 고종이 어떠한 생존전략을 채택하였는지를 상징적으로 보여주는 것이었다.

조약 체결 이후 미국에서는 공사를 파견하고 서울에 공사관을 설치하였다. 조선 정부에서는 미국인 교사와 군인을 초빙하고 선교사의 의료와 교육 사업을 허락함으로써 이들을 통해 본격적으로 서구 문물과 제도가 소개되었다. 또한 미국의 공사 파견 이후 조선 정부에서 파견한 민영익을 정사로 하는 보빙사 일행은 미국에 도착하여 체스터 A. 아서 미국 대통령을 접견하고 40여 일 동안 박람회, 방적 공장, 농장, 신문사, 소방서, 우체국 등 미국의 각종 시설을 시찰하였다. 이들의 경험은 이후 조선 정부가 추진하는 근대화 사업에 밑거름으로 작용하였다.

황제의 자리에 나아가다

고종과 조선 정부가 추진한 근대화 사업은 순조롭지만은 않았다. 조선 사회를 지탱해 온 전통을 고수하려고 하는 조선 사회 내부의 사회적 저항은 물론, 조선을 둘러싼 열강의 대립 속에 각종 근대화 사업은 좌초되었다. 근대적 제도를 도입하여 사회를 근대화함으로써 나라의 독립을 유지해야 했으나 나라의 독립이 보장되지 않는 한 근대국가로의 체질 변환 역시 기약할 수 없는 역설적인 상황이었다. 고종은 갑신정변(1884), 동학농민운동(1894), 청일전쟁(1894~5) 등을 연이어 겪으며 나라의 독립을 확고히 하고 주권을 다시 세워야만 하는 상황에 직면했고, 1897년 대한제국을 선포한 뒤 황제의 자리에 오름으로써 해결의 실마리를 마련하고자 했다.

'대례의궤'는 당시 고종이 황제에 자리에 나아가기 위한 준비 상황과 그 절차들을 기록하고 있다. 세계 각국과 동일한 독립국가로 인정받으려면 우선 청나라와 동등한 독립국가임을 내세울 필요가 있었고, 이를 위해 고종이 중국의 황제와 다름없는 황제의 지위에 오름으로써 그 위상을 다시 세워보고자 한 것이다. 전통적으로 중국의 황제가 사용하였던 황색과 용 문양 등을 의식적으로 활용하면서 변화된 위상을 드러내고자 했다. 대례의궤 속에는 황제의 지위에 올랐음을 하늘에 고하기 위해 환구단으로 향하는 황제의 행렬이 묘사되어 있는데, 황제 즉위식에 필요한 황제의 어새를 싣고 가는 황금색 가마가 선명히 보인다. 고종은 황제를 상징하는 황색 곤룡포를 입고, 금색 용교의에 앉아 용 모양의 손잡이로 제작된 국새를 받았다. 황제의 권위를 나타내기 위한 이와 같은 의장물들은 대례의궤 속에 상세히 기록되어 있다.

부국강병을 추구한 대원수

황제의 자리에 나아간 고종은 보다 적극적으로 이른바 ‘부국강병’을 추구해 갔다. 대한제국 선포를 전후하여 서울 곳곳의 도로가 정비되고 전등과 전화가 가설되는 한편, 전차가 다니기 시작하면서 서울의 모습은 크게 달라졌다. 1902년에는 마포~개성 구간 철도 부설이 시작되었다. 궁내부 산하 각 관서에 전환국, 인쇄국, 평식원, 도량형 제작소, 양잠소, 한성전기회사 발전소 등을 설립하여 정부 주도로 각종 산업시설을 육성해 갔다. 또한 은행을 설립하여 산업발전의 근간으로 삼고자 했다.

이와 같은 산업 육성 정책과 더불어 자주독립국가의 지위를 보장하기 위한 ‘강병’ 정책도 추진해 갔다. 원수부를 설치하여 군사 조직의 정점에 두고 황제 자신이 대원수가 되었던 것은 황제가 중심이 되어 병력 강화를 추진하고자 한 고종의 뜻을 단적으로 보여준다. 프랑스와 일본, 프로이센의 제도를 참작하여 만든 대원수복과 투구를 착용한 고종의 모습은 ‘부국강병’을 통해 대한제국을 근대적으로 변모시키고 이를 통해 나라의 주권을 수호하고자 했던 고종의 의지를 상징적으로 보여주고 있다.

희망을 되살리기 위한 마지막 노력

13년이라는 대한제국의 역사 속에 응축된 근대화와 자주독립을 위한 노력에도 불구하고 1905년 을사늑약을 고비로 대한제국의 국권은 차츰 기울어갔다. 1904년 러일전쟁의 승리로 한반도를 둘러싼 열강의 대결에서 거의 독점적 권한을 갖게 된 일본은 한일의정서(1904), 을사늑약(1905), 정미조약(1907) 등 대한제국에 차례로 조약을 강제하여 대한제국의 주권을 잠식해 갔다. 이러한 상황에서 고종은 각국 원수에게 친서를 보내 대한제국의 독립권을 보장받고자 하였다. 특히 을사늑약 체결 이후 외교 활동이 크게 제약된 상황 속에서 고종은 비밀리에 친서를 보내 대한제국의 상황을 각국에 알리고 일본에 박탈당한 외교권을 되찾을 수 있도록 지지를 호소하였다.

인면에 ‘황제어새(皇帝御璽)’라는 네 글자가 양각된 〈대한제국 고종 황제어새〉는 일본의 감시 속에 펼쳐진 고종의 비밀 외교에 활용된 어새이다. 이 어새는 대한제국 황실의 각종 인장에 대해 기록한 〈보인부신총수〉에 조차 실려 있지 않다. 이는 고종이 비밀 외교를 위하여 이 어새를 국새를 관장하는 직제를 통하지 않고 비공개적으로 사용하였기 때문이다. 〈황제어새〉가 대한제국 시기의 일반적인 국새보다 작은 크기로 만들어져 몰래 간직하기 적합하게 제작되었던 것도 그 때문이었다. 이 작은 어새에서 대한제국의 화려한 출발과 위용을 찾을 수는 없지만, 힘든 상황 속에서도 대한제국의 독립을 지켜나가고자 했던 고종의 마지막 노력이 오롯이 담겨 있다.

개항을 전후로 서양에서 유통된 한국에 대한 여행기, 지리지 등에서는 ‘고요한 아침의 나라’라는 이미지가 널리 회자되었다. 한적하고 평화로운 나라라는 느낌을 주는 이러한 수식어 이면에는 스스로 발전을 이루어낼 동력이 없어 다른 나라의 지배를 받는 것을 정당화하는 제국주의적인 시선이 전제되어 있다. 고종 역시 무능하고 무기력한, 그래서 주권이 강탈당하는 상황 속에서도 아무런 대응을 하지 못한 왕이라는 이미지가 덧입혀져 있었다. 그러나 비록 단편적으로 살펴보았을 뿐이지만 위에서 언급한 고종과 관련된 몇 가지 유물들은 이 시기 한국 사회가 겪어야 했던 역사적 경험들이 결코 평화롭지도, 고요하지도 않았으며, 고종은 그와 같은 위기 속에서 치열하게 자기 변화를 모색하고 있었음을 알게 해 준다.

글 김재은(문화재청 덕수궁관리소 학예연구사)

사진서울대학교 규장각, 세종대학교 박물관, 국립중앙박물관, 국립고궁박물관