Feature

Buchae: Traditional Fans Stir the Air with Dignity

By Geum Bok-hyun

Since time immemorial, people have employed a range of devices to respond to seasonal changes. One example is fans, which were used to provide a cooling breeze in the sweltering summer heat. Originally, large, durable leaves were used to move the air, but the form evolved continuously with the adoption of new materials such as feathers, silk, and paper. In Korea, handheld fans signified the dignity and tastes of their users and formed an intrinsic component of a number of customs. Koreans of the past would beat out a rhythm with their fans as they recited poetry, and they took pleasure in exchanging them as gifts. Traditional fans were much more than simple cooling devices for Koreans.

History of Traditional Fans

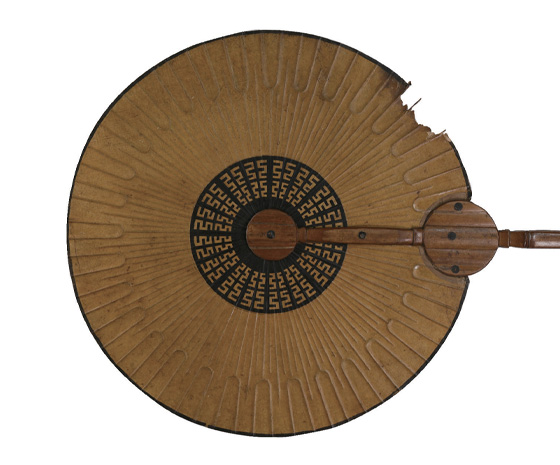

A fan featuring warped ribs, the rendering of which requires a high degree of dexterity

The world’s oldest fans are those discovered in the tomb of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun from the fourteenth century B.C. The first known evidence of a fan in the East is a lacquered fan handle excavated from a tomb in Dahori in southeastern Korea. Originally made with feathers, only the handle of the Dahori fan relic has survived. It is purported to have been made before the three ancient kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla came to dominate the Korean Peninsula during the Three Kingdoms period at the start of the Common Era. Fans are also found among relics from Goguryeo (37 B.C.–A.D. 668). The Goguryeo-era Anak Tomb No. 3 in Hwanghae Province in present-day North Korea features murals showing human figures holding fans. Murals at the Takamatsuzuka Tomb in Japan also depict female attendants holding round, rigid fans with long handles following behind a main figure who appears to hail from Goguryeo.

Among the surviving relics from the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) is a handheld fan exhibited in the Treasures Hall of Taesamyo Shrine in Andong, Korea, which is dedicated to the spirit tablets of three meritorious officials who made critical contributions to the foundation of Goryeo. This handheld fan with a lacquered wood mount and handle are believed to have belonged to Princess Noguk, the wife of Goryeo’s thirty-first ruler Gongmin (r. 1351–74). When the royal couple visited the shrine to pay tribute to the dynastic founders, the princess happened to leave her fan behind. This royal accouterment has been maintained at the shrine ever since.

The earliest textual evidence of a fan comes from the twelfth-century Korean history Samguk sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms). It is recorded that when Wanggeon (r. 918–43), the founder of Goryeo, ascended to the throne, the leader of the Later Baekje Kingdom, Gyeonhwon, sent him a handheld fan trimmed with peacock feathers as a congratulatory gift. Wanggeon held this fan at his enthronement ceremony, but not as a means to move the air. It was intended to express his commitment to protect the dynasty from wind, which symbolized war or misfortune at the time and was understood as a harbinger of pending disaster.

The Many Varieties of Korean Handheld Fans

Left _ A rigid handheld fan for weddings, lavishly embroidered with peony flowers

Center _ A court lady’s fan made from embroidered silk

Right _ A painted fan rendered in the shape of a banana leaf

The Chinese character seon (扇) meaning “a handheld fan” is comprised of two components (戶 and 羽) meaning “a house” and “feathers.” Together they denote “feathers inside the house.” Its Korean equivalent buchae is a pure Korean word, consisting of bu meaning “move air” and chae meaning “a tool.”

Traditional Korean handheld fans come in more than one hundred variations depending on the materials involved, inclusions of embroidery, and the intended occasions for its use. Plumage fans can be divided into different types according to the kind of a bird and the color of the feathers, like fans made from the tail feathers of male pheasants, their body feathers, or those of owls or peacocks. Hemp or silk can be used with fabric fans, and silk fans are categorized into those with and without embroidery. There were distinctive fans serving as a regal accessory, and others as a ritual object at a wedding for royalty or nobility.

The development of Korean paper in the eighth century during the Unified Silla period (676–935) provided a critical boost for the development of diverse types of handheld fans. Made from the inner bark of mulberry trees, Korean paper is both light and durable, providing an ideal material for handheld fans. Diverse kinds of paper fans were crafted, such as those painted with a taegeuk (supreme ultimate) symbol, inscribed with a poem, or decorated in a flower and butterfly motif. Others resembled the form of the tail of a carp, while still others featured warped ribs for decorative purposes. There were lacquered fans as well.

Traditional Korean handheld fans boast a simple but delicate aesthetic. One of its outlets is the decoration on the head of the handles of rigid fans where the component ribs are gathered. Rendered thick and sturdy, the head of the fan handle is commonly ornamented with one of a diverse range of motifs, a distinctive characteristic unique to traditional Korean fans.

One of the definitive Korean hand-fan forms is the hapjukseon, meaning “a handheld fan with the ribs individually made by attaching two bamboo strips.” A folding type of fan, one variation of hapjukseon has as many as fifty ribs and one hundred folds. The lightness and durability of Korean paper allows the creation of this type of fan.

Folding Handheld Fans for Style and Dignity

Left _ folding fan coated in lacquer, which creates a brilliant and waterproof surface

Right _ A hapjukseon folding fan made with thin bamboo strips as its ribs

The Chinese travelogue Xuanhe fengshi gaoli tujing, an account of a diplomatic mission to Korea written by the Chinese emissary Xu Jing during the Song dynasty (960–1279) records that “People in Goryeo carry with them handheld fans even in winter. These fans are of an interesting variety, which is folded and unfolded and therefore convenient.” From this, it is inferred that folding handheld fans, called jeopseon, had already come into wide public use by the Goryeo public even before they were known in China.

A folding handheld fan from the Goryeo era that demonstrates a great level of dexterity and dignity was excavated in Hwanghae Province. Guarded by a thick metal rib at either end that was ornamented using the silver inlay technique, the wooden slips are clutched together by a silver rivet at the base decorated with a fish motif coated in gold. Suspended from the rivet are a chain and a pendant that are also covered in silver. Its exquisite crafting matches that of fans used exclusively by kings.

After its invention, the folding fan quickly became a necessary part of the paraphernalia of the literati class for their outings. It was a customary practice in Goryeo for aristocrats to always carry a folding fan, regardless of season. They used the fan in the hand to create a cooling breeze in summer and to buffer the freezing wind in winter. They could also avoid people or things they did not wish to encounter by covering their faces with the fans. While reciting a poem, their handheld fans served as batons to mark the rhythm.

Fans Offered as Gifts

Handheld fans were given as diplomatic gifts throughout the Goryeo era, and in the following dynasty of Joseon (1392–1910) as well. Goryeosa (History of Goryeo), a fifteenth-century Korean history, recounts that painted fans were sent to the Yuan Dynasty in 1232 on a diplomatic mission from Goryeo to this Mongol dynastic rule established in China. Examples of hand fans adopted as political gifts during the Joseon period include an offering to the Ming Dynasty of ten rigid and eighty-eight folding fans in 1426 during the reign of King Sejong and of fifty folding fans presented in 1452 during the reign of King Danjong, both through visiting Chinese emissaries. Tongmungwanji, an eighteenth-century compilation on foreign relations with China and Japan, relates that handheld fans were also part of the Joseon diplomatic offerings by the embassies to Japan.

Left _ A fan showing a taegeuk symbol in the center

Right _ A fan embodying a taegeuk (supreme ultimate) symbol and embroidered with a flower and butterfly motif

Fans were presented as royal gifts as well. Emperor Shun, a legendary leader of ancient China, fashioned special fans called wumingshan and offered them as gifts to those who performed good acts or recommended good candidates for employment as a way of hiring people of talent and wisdom. In Goryeo as well, kings would celebrate Dano, a seasonal holiday falling on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month signifying the beginning of summer, by awarding people fans for their benevolent acts. Those recognized for even greater goodness received multiple fans, and they would pass them along as gifts to those senior in age or to whom they felt grateful. These fans endowed by a king sustained their holders through the summer. The practice of exchanging fans as gifts on Dano took hold among the Korean people and has been transmitted until the present.

Despite living in an age of automatic air conditioning, many Koreans cherish memories of handheld fans deeply in their hearts. My mother and I used to rest on a straw mat in our courtyard on sweltering summer days. I still vividly remember her chasing away mosquitoes and softening the heat with a handheld fan as she narrated interesting stories to me. I still miss the pleasant breeze created by her fan and treasure the memories of those summer days with my mother.

Text and photos by Guem Bok-hyun, Cheonggok Fan Museum

품위와 건강을 선물하다, 부채

사람들은 아득한 옛날부터 계절의 변화에 적응하기 위해 다양한 도구를 사용했다. 그중에는 더위를 식히기 위한 부채도 있었다. 단순히 크고 질긴 나뭇잎으로 바람을 일으키던 것이 새의 깃털, 비단, 종이에 이르기까지 변화를 거듭해왔다. 특히 우리나라에서 부채는 멋이자 격, 그리고 풍속이었다. 시를 읊을 때면 부채를 이용해 장단을 맞췄고, 귀한 사람에게는 부채를 선물했다. 부채가 일으키는 바람에는 많은 의미가 담겨있었다.

부채의 역사와 의미

세계에서 가장 오래된 부채는 투탕카멘의 피라미드에서 발견된 것이다. 황금 봉에 타조의 깃털을 꽂아 만든 것으로, 깃털은 삭아 없어지고 자루만 남아있으나 자루 구멍의 찌꺼기를 분석하여 타조의 깃털임을 알아냈다. 동양에서는 경남 다호리 고분에서 출토된 ‘옻칠된 부채 자루’가 가장 오래된 부채로 여겨진다. 이 역시 깃털 부채 자루로, 약 2천 년 전 원삼국 시대에 만들어진 것으로 추정된다. 그러나 황해도 안악군의 안악 3호 고분벽화에 깃털 부채를 든 인물상이 보이고, 일본 다카마스(高松) 고분 벽화에 고구려 계통으로 추측되는 주인공 뒤로 자루가 길고 선면이 둥근 부채를 든 시녀들이 서 있는 것으로 보아, 고구려 시대에 이미 자루가 달린 단선(둥근 모양의 부채)이 있었음을 짐작할 수 있다.

고려 유물로 전해지는 부채도 있다. 고려의 개국공신 세 명을 모신 안동 태사묘 보물각에 보관된 것으로, 공민왕과 노국공주가 참배를 왔을 때 노국공주가 늘 들고 다니던 부채를 두고 간 것이 지금까지 전해지고 있다. 얇은 선면에 옻칠을 한 나무 테두리와 자루로 되어 있다.

우리나라 문헌에서 부채에 대해 가장 오래된 기록은 《삼국사기》에 있다. 고려의 태조 왕건이 왕으로 즉위하자, 후백제 황견훤이 축하의 선물로 공작 꼬리깃으로 만든 부채를 보냈다는 것이다. 당시 왕은 취임식 때 부채를 들었는데, 이는 바람을 일으킨다는 것이 아닌, ‘부채로 바람을 막는다.’는 의미였다. 당시 바람은 전쟁이나 액운을 상징하여 바람을 일으키면 나라에 전쟁이나 환란이 온다고 여겼기 때문이다.

백 가지가 넘는 우리나라의 부채

한자의 부채 선(扇) 자를 보면, 집 호(戶) 자와 깃 우(羽) 자가 합쳐진 모양이다. ‘집 안에 있는 날개’라는 뜻이다. 우리나라에서는 손으로 부친다는 뜻의 ‘부’와 도구를 뜻하는 ‘채’를 합친 순우리말, 부채라고 부른다.

우리나라의 부채는 그 종류만 해도 100종이 넘어 다 나열하기 어려울 정도다. 깃털을 재료로 하는 부채(우선)만 살펴보아도 수꿩의 꼬리로 만든 치미선, 검정 깃털로 만든 흑우선, 부엉이 깃털로 만든 광우선, 공작의 깃털로 만든 공작선 등 새의 종류나 깃털의 색에 따라 이름이 붙는다. 천으로 만든 단선에도 명주를 이용한 명주선, 모시를 이용한 모시 부채 등 사용한 천의 종류와 비단에 수를 놓은 수선 등 문양에 따라서도 구분이 된다. 왕이 장식으로 들던 용수선과 궁중 혼례에 사용되던 진주선, 양반가 혼례 때 쓰던 혼선 등 역할에 따라 나뉘기도 한다.

신라 시대에 한지가 발명되며 부채는 급속도로 성장했다. 한지는 닥나무 속껍질을 이용해 만드는데, 가볍고 질긴 데다 수명 또한 길어서 부채를 만들기 좋았다. 종이부채에는 태극 문양이 있는 태극선, 시가 적힌 시선, 꽃과 나비가 그려진 화접선, 붕어 꼬리 모양의 미선, 살을 구부려 멋을 낸 곡두선, 옻칠을 한 칠선 등이 있다.

우리나라의 전통 부채는 단순하면서도 정교하고 얇아 가벼우면서도 견고하다. 또 단선의 부채 자루를 고정하는 부분은 두껍고 튼튼하며 문양 꽂지를 붙여 멋을 내었다. 이러한 꽂지는 문양을 오려 붙이기가 쉽지 않은데, 오로지 우리나라 부채에만 있는 특징이다.

이뿐만이 아니다. 접선(접는 부채) 중에는 50개의 부챗살을 가져 백 번을 접어야 하는 백접선이 있다. 한지가 얇으면서도 질기기에 가능한 것이다. 얇은 대나무 겉껍질을 합죽(얇은 댓조각을 맞붙임)하였다 해서 합죽선이라 부르는 부채도 있다.

멋과 권위의 상징이었던 접선

700여 년 전 송나라 때 사신으로 왔던 서긍은 고려의 여러 풍물을 보고 돌아가 《선화봉사고려도경》을 지었다. 그 안에는 ‘고려인들은 한겨울에도 부채를 들고 다니는데, 접었다 폈다 하는 간편하고도 신기한 부채를 사용한다.’고 적혀있다. 이 기록으로 미루어 보아, 접선은 중국에 없던 시절부터 고려에서 일반화되어 있었던 것으로 추측된다.

또 고려 때 만들어진 접선이 황해도 지방에서 출토되어 20여 년 전 우리나라를 방문한 적도 있다. 갓대(부채의 양쪽에 대는 두꺼운 조각)가 금속으로 되어 있고 은상감(무늬를 세긴 후 은을 박아 넣는 공예 기법)이 아주 정교한 부채였다. 은으로 된 고리 장식은 한 쌍의 물고기 문양에 도금이 되어 있고, 부채 고리에 늘어트리는 장식과 줄도 은에 도금을 했다. 왕이 썼던 것으로 추정될 만큼 정교하고 고급스러운 모습이다.

접선은 발명된 이후 양반들이 외관을 갖춰 입고 손에 부채를 쥐어야만 비로소 외출하는 풍속이 생길 정도로 보편적인 물건으로 자리 잡았다. 고려 때부터 양반들은 계절과 관계없이 접선을 쥐고 다니며 여름에는 더위를 식히고 겨울에는 찬바람이나 먼지를 막았다. 빚쟁이나 거북한 상대를 만나면 얼굴을 가리기도 했고, 더러운 것이나 가증한 것을 피하는 데 쓰기도 했다. 시조라도 한 수 읊으려면 부채로 먼 산을 가리키거나 장단을 맞추며 흥을 돋우었으니, 부채는 단순히 바람만 일으키는 도구가 아니었다.

부채로 '품격'을 선물하다

우리나라 부채는 국교품으로서 일찍이 사절을 통해 중국이나 몽골, 일본 등 여러 나라로 진출하였다. 《고려사》에 따르면 1232년 원나라에 사신을 보낼 때 그림을 그려 넣은 부채를 함께 보낸 일이 있다. 1426년 세종대왕은 명나라 사신이 부채를 구하자, 방구부채 10자루, 접부채 88자루를 하사하였고, 1452년 단종은 명나라 사신을 통해 접부채 50자루를 보내기도 했다. 특히 접부채는 중국 송나라 때부터 원·명·청대에 이르기까지 주요 국교품의 역할을 하였다. 이 밖에도《통문관지》에는 조선시대에 우리나라 사신 세 사람이 일본에 갈 때에도 국교품으로 부채를 가져간 일이 있다고 적고 있다. 이렇게 오래전부터 부채는 국교품으로 그 가치를 발해왔다.또 고대 중국의 순임금은 어질고 현명한 인재를 등용하기 위해 오명선이라는 부채를 만들어 좋은 일을 많이 한 사람이나 좋은 인재를 추천하는 사람에게 선물로 주었다고 한다. 고려의 한 임금도 더위가 시작되는 단옷날이 되면 좋은 일을 많이 한 사람에게 부채를 선물했다고 한다. 좋은 일을 많이 한 사람에게는 더 많은 부채를 주어 웃어른이나 은혜를 입은 사람에게 선물할 수 있도록 했다. 임금에게 받은 귀한 부채는 더운 여름 요긴하게 사용되었고, 이것이 시초가 되어 단옷날 부채를 선물하는 풍습은 지금까지 이어져 오고 있다. ‘여름 생색은 부채요, 겨울 생색은 책력(책으로 엮은 달력)이다.’라는 속담 또한 이러한 풍습에서 나온 것이다.

이제야 실내에 들어서면 시원한 공기를 만날 수 있는 시대이지만, 부채에 얽힌 추억 하나쯤은 가지고 있는 사람들이 대부분이다. 어린 시절, 무더운 여름이면 밀집으로 만든 밀대 방석을 마당에 깔고 모기향을 피우며 옛이야기를 해주시던 어머니는 연신 부채로 모기를 쫓고 더위를 식혀주셨다. 아직까지도 그 부채 바람이 새삼 그리운 것을 보면, 부채가 가져오는 바람에는 깊은 애정과 많은 이야기가 담겨 있었던 듯하다.

글/사진 청곡부채연구소장 금복현