Feature

Masters of Lacquer Freeze Time

By Mogun Lacquerware Workshop

Lacquer, a durable material produced from the sap of the lacquer tree, is applied mostly to wood, but it can also be used on metal and other materials. It is widely known that lacquer provides a surface gloss, but it also protects the object from fluctuations in temperature and humidity and from attacks by insects.

Weaving of Ramie Fabric as Global Intangible Heritage

Master Park Gang-yong

Lacquer can absorb or release moisture depending on the surrounding environment, which helps maintain a stable level of humidity. A coating of lacquer provides objects of various materials and diverse uses with a solid layer of protection that offers luster to their surfaces and enhances their durability. Due to these attributes, for more than four thousand years lacquer has been widely applied in both the West and the East to decorative and everyday objects, and even to armor.

The Many Kinds of Lacquer

In Korea the extraction of lacquer mostly takes place from mid-June until mid-October or early November. Since lacquer trees most actively produce sap in the early hours, the prime time for the operation falls between 4:30 a.m. and 3:00 p.m.

Lacquer comes in two types depending on the extraction method. One is drawn from cuts in the skin of a lacquer tree and is mainly used for making crafts or for industrial purposes. Another kind of lacquer sought for medical uses is extracted by applying heat to lacquer tree wood that has been soaked in water for roughly one week.

Differences in processing also result in distinct lacquer types. Sap from lacquer trees can simply be stripped of impurities to be ready for use as raw lacquer. The raw lacquer can also be put through further processing steps‐such as heat treatment for the elimination of moisture to enhance transparency and purity, and sometimes be blended with other substances such as camellia oil‐to become refined lacquer.

Lacquer Master Park Gang-yong

Masters of the lacquerware crafting possess knowledge and skills across the full process of creating lacquered works‐extracting lacquer, processing it, and applying the

organic resin to the surface of objects. One of the most prominent lacquer masters in all Korea is Park Gang-yong. He is a vital driving force behind the widespread popular

use of wooden lacquerware in everyday life.

Born in Jeongeup, Jeollabuk-do Province in 1964, Park went to Seoul for training under the instruction of the established lacquer master Lee Ui-sik. In 1992 he moved to Namwon, an area in Jeollabuk-do with a longstanding reputation for wooden lacquerware. He settled there rather than his nearby hometown based on his resolution

to dedicate the rest of his life to the creation of lacquerware.

Park initially practiced using raw lacquer in the traditional manner, but soon realized that it possesses a critical shortcoming: raw lacquer cannot survive temperatures surpassing 60 degrees Celsius. This does not pose a problem for dishes or bowls intended as monastic vessels or for ritual tables, but it is detrimental to anything to be used as household utensils.

Later, Park learned skills for producing refined lacquer from nationally designated Master Jeong Su-hwa. After undergoing heat treatment, refined lacquer can sustain temperatures of 200 degrees Celsius and above, and can therefore be used for everyday items as well as monastic utensils and ritual dishes. In addition, refined lacquer provides a more refined shine rather than a glaring surface and can be freely mixed with diverse colors.

Raw lacquer is applied to a wooden object.

Lacquer utensils in wood widely used by the public

Master Park has maintained a life-long passion for making lacquerware. In 2008 he was recognized as a master of lacquerware at the Jeollabuk-do provincial level, and his artworks have won awards at several significant contests, including the Craft Transmission Festival of Korea and the National Craftwork Festival. He is currently operating the Mogun Lacquerware Workshop in Namwon and supporting the transmission of lacquerware skills and know-how to future generations.

Process of Wooden Lacquerware

While various species of trees can be used for the base object, including the needle juniper, ginkgo, tree-of-heaven, and pine, the wood of choice and method of production may differ depending on the intended usage and form of the finished product.

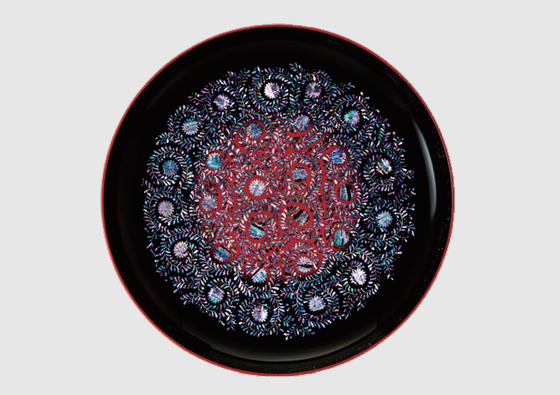

Mother-of-pearl lacquerware

The process of lacquerware making starts with sanding an uncoated wooden frame to smooth its surface. Next, the frame is applied with a first round of coating using a diluted raw lacquer. The object is transferred to a drying room at 70–75 percent humidity where it is dried for between three and seven hours (although sometimes it takes as many as 18). It is removed from the drying room, applied with a mixture of raw lacquer and clay to fill any gaps on the surface, and sanded once again.

The object surfaced with the lacquer-clay mixture is then coated with refined lacquer, dried, and sanded. The process of applying refined lacquer, drying, and sanding isrepeated four or five times. Then, refined lacquer is additionally applied seven or eight times for the enhancement of the strength and transparency of the coating. Only after this long and

arduous process is a wooden lacquer craft considered complete.