Feature

Dolmens Offer Rare Glimpses into the Lives of Prehistoric Humans

By Text by Kang Dong-seok, Professor in Archaeology and Art History, Dongguk University Photos by Cultural Heritage Administration,

Megaliths from the Bronze Age

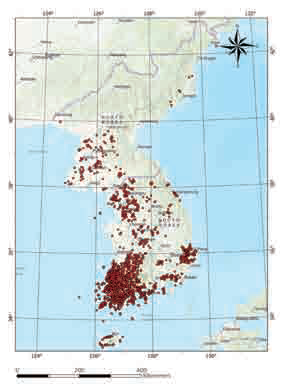

Distribution of dolmens on the Korean Peninsula

Dolmens epitomize the megalithic culture of the Bronze Age on the Korean Peninsula. They occur around the world from Northern and Western Europe, through the Mediterranean, and across Asia. However, nowhere else in the world shows the concentration of dolmens found in Korea. An estimated 40,000 dolmens were constructed here over the course of the 15,000 years from the 15th century BCE to around the start of the Common Era.

Diverse Forms

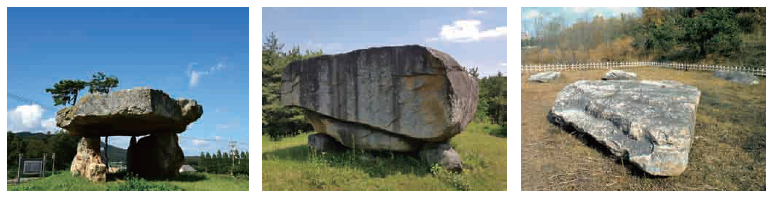

Dolmens in Korea generally come in three forms. The first is known as table-type dolmens.

These structures consisting of two or more upright stones supporting a large horizontal

stone look similar to the Poulnabrone dolmens in Ireland. Table-type dolmens are mostly

scattered in the western reaches of present-day North Korea, but a small number of

examples have been found in South Korea (mostly on Ganghwa Island and the Imjingang

River basin). In the second type, a large stone is set on top of smaller stones over a tomb.

This form is known as go-type, as it resembles the wooden table used to play the game go.

These go-type dolmens predominantly occur in the southwestern section of the Korean

Peninsula. The third category is a single large stone laid flat above a tomb with no smaller

stones as a base between. This type of dolmen can be found across the Korean Peninsula.

While this typological categorization provides a useful overview, the precise configurations

differ by region and era.

Left A table-type dolmen at Jeom-gol Village in Ganghwa County

Center A go-table type dolmen at Yuri Village in Changyeong County

Right A stone covered type dolmen at Naedong-ri in Daejeon City

Stone Monuments and Collective Identity

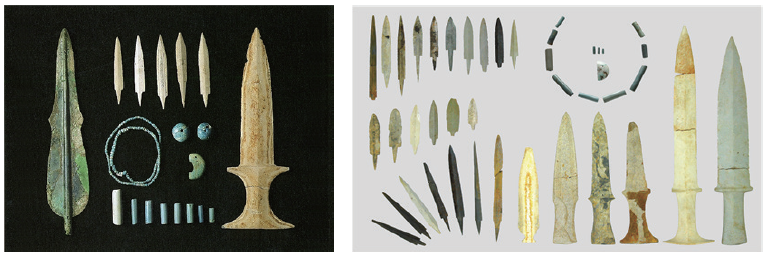

Burial chambers found under dolmens have produced grave goods. They commonly include weapons such as bronze daggers (both Liaoning-type and Korean-type), polished stone knives, and stone arrowheads. Earthenware vessels and jade personal accessories have also been recovered. These finds indicate the status and power of the people interred within the tombs, hinting at the presence of social stratification at the time. Dolmens are understood primarily as burial sites. They remain a critical source of information on the burial methods and funerary ceremonies of Bronze Age Korea. Dolmens also serve as evidence of the existence of an elite class that possessed enough power and authority to mobilize the difficult labor required for moving large stones and organizing them into megalithic structures. In addition, dolmens suggest how people on the Korean Peninsula came together as members of a community and formed collective identity by constructing these monumental structures. Building a dolmen meant creating a new landscape, a sociocultural act that was driven by the ideas held by Bronze Age people regarding their lives and their relationship with the environment. While fundamentally facilities for the dead, dolmens help us to understand much about life.

Left Artifacts excavated from dolmens in Suncheon City and Yeosu City

Right Grave goods from dolmens at Maechon-ri in Sancheong County

Korean Dolmen Sites as World Heritage

Among the many dolmen sites in South Korea, three of the most important ones were selected and nominated for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The three sites found in Gochang, Hwasun, and Ganghwa earned World Heritage status in 2000 when they were recognized for their significance in illustrating the megalithic culture of humanity. The Gochang site is home to 447 dolmens, most of which are found in the Jungnim-ri neighborhood. This spot boasts the highest concentration in the entire Gochang area and features diverse types of dolmens. With only a few exceptions, dolmens at the Gochang site distribute in groups along the borderline between agricultural fields and a hilly area. This suggest that Bronze Age people made a conscious choice when selecting a site for building a dolmen. Dolmens were positioned in between the place where they lived and farmed and the area where hunting and gathering took place. Dolmens served as a boundary marker between these two different spaces. Moving between these two territories with their distinct functions, Bronze Age Koreans must have regularly come across the dolmens and been reminded of the leaders buried there. This would have inspired them to think about their currently ruling successors and develop their sense of belonging to a community. A particularly noteworthy element of the Gochang site is a table-type dolmen in Dosanri, the area neighboring Jungnim-ri. There is also a distinctive local form known as pillartype, a modified version of the go-type, which can be found across the Gochang area. The Dosan-ri dolmen is the southernmost table-type example in South Korea. It occurs in isolation on the top of a hill. Its location indicates that its primary function was to mark the territory of the social group responsible for constructing dolmens in the Jungnim-ri neighborhood. Many pillar-type dolmens are also found in isolation on the summit of a hill apart from the dolmen clusters at the foot of hilly areas, suggesting that they played the same role as that of the table-type dolmen in Dosan-ri.

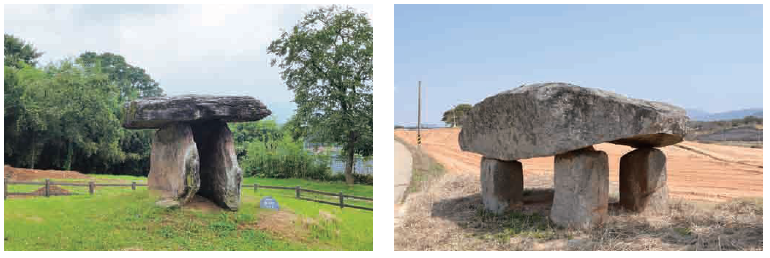

Left A table-type dolmen in Dosan-ri in Gochang County

Right A distinctive local form of a dolmen at Hyangsan-ri in Gochang County, known as pillar-type

The Hwasun site hosts the greatest number of dolmens among the sites in South Korea. There are 596 dolmens here spread across six sub-sites. They are mostly go-type or stone covered type. Among them is a dolmen of outstanding size known as pingmae bawi. This go-type dolmen is capped with a grand stone seven meters long, four meters high, and weighting approximately 200 metric tons. This imposing dolmen is associated with enduring local legends. An old woman named Mago Halmeon (“Witch Grandmother”) carried stones in her skirt to help build a pagoda at a Buddhist temple. The stones that dropped from her skirt became this monumental dolmen. Another story relates to its name pingmae bawi, meaning “throwing a stone.” If a person succeeds in throwing a stone onto the top of the dolmen, their wishes will come true. These folktales can be seen as an expression of the respect and awe local communities held toward this megalithic structure. It is estimated that there are approximately 160 dolmens on Ganghwa, an island near the estuary of the Hangang River. They are mostly found in the northern section of the island. Here, dolmens form small groups on hillslopes or on the summit of a low-rising hill. Large dolmens were sometimes placed here in isolation on flat lands. There are also cases where a group of dolmens are found at high elevations, with one cluster as high as 400 meters above sea level.

Dolmens on Ganghwa Island mostly take the form of a table or a single large stone. The table-type dolmens here are typologically the same as those found in Pyongan-do and Hwanghae-do in present-day North Korea, forming the highest concentration of this type in South Korea. The dolmen at Bugeun-ri is a definitive example of the table-type dolmens on Ganghwa. This large table-type dolmen is found alone amid wide stretches of flatland, measuring 2.6 meters high in total. Its capstone is 6.5 meters long and 5.2 meters wide. This massive structure stands along the wide flats connecting the northern section of Ganghwa Island to the south, making it well positioned to serve as a focal point for meetings among the people of the island. Local peoples would have gathered here and collaborated to build this large stone structure. This collective funerary ritual must have boosted their identity, belonging, and solidarity. Ever since its construction, the monumental stone structure has been integrated into the memory of local communities and provided a landmark.

A large dolmen in Hwasun County (Right Dolmen known as pingmae bawi)

Imposing Evidence of Prehistoric Culture

A cluster of dolmens at Osang-ri in Ganghwa County

It was necessary to place the Iryeongwongu in the right setting before it could be used to Dolmens were more than just facilities for burying the dead in Korea. They were part of the process of expressing ideas about death and the life that comes after it. Dolmens were also the result of social stratification and the emergence of an elite. Leadership groups adopted dolmen construction as a means of placemaking through which they could nurture a collective consciousness among members of the community and strengthen their political power. Community members came to perceive dolmens as an integral part of their everyday landscape. Dolmens in South Korea are an invaluable source of information for understanding the complexities of ancient culture and society. The Gochang, Hwasun, and Ganghwa sites collectively registered as a World Heritage property merit sustained global attention for the protection of their critical contributions to the understanding of human history.

A table-type dolmen at Jeom-gol Village in Ganghwa County