Feature

Listed Traditional Alcoholic Drinks

By Text and Photos by Yang Jin-jo, Research and Archiving Division, National Intangible Heritage Center

Alcoholic drinks have long been deeply intertwined in the lives of Korean people. A cup of wine enhanced the joy of social gatherings, and community celebrations and rites of passage were not considered complete without the alcohol presented as an offering to deities. Diverse kinds of alcoholic beverages were developed depending on their intended uses and consumers. Some of the many recipes for making traditional Korean alcoholic drinks have been carefully transmitted to the present as local traditions or family heritage.

Listing and Safeguarding

In traditional Korean society, alcohol was conceived as being in line with good health, not something detrimental to it. Koreans of the past made alcoholic beverages using the same grains they consumed as staples. Based on the long-entrenched belief that “everyday food is medicine,” Koreans treated alcohol as part of the culinary elements they could use to maintain their health.Efforts have been underway to identify alcohol-making traditions with distinctive characteristics and enter them onto the national intangible heritage list to support the transmission of traditional recipes for alcoholic beverages. This article explores the traditional Korean alcoholic drinks that have been placed under the guardianship of the state as an important part of the country’s intangible heritage.

A brewery making traditional Korean alcohol

A Cloudy Beverage for Popular Consumption

One traditional alcoholic beverage recently registered on the national intangible heritage list is makgeolli, a cloudy low-alcohol beverage that earned national heritage status in June 2021. The designation of makgeolli is particularly noteworthy as its impetus came directly from the public. The Cultural Heritage Administration made a nationwide call in 2019 for national intangible heritage candidates by organizing a public contest and through a petition-submission channel. Makgeolli was selected as a finalist through this process and was eventually entered onto the list. It was the first listing initiated by members of the public since the intangible heritage registration system was operationalized in 1964. Its widespread popularity, history supported by documents dating back to the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–668 CE), and robust transmission communities nationwide were all positively evaluated when determining its registration.It is estimated that this milky rice beer can trace its history far beyond the Three Kingdoms period and back to the introduction of farming to the Korean Peninsula. Makgeolli, along with other typical fermented foods of Korea such as kimchi and soybean- based sauces, was made by individual households. It played an important role in agriculture as the drink with which farmers quenched their thirst while working in the fields. It was usually offered along with snacks or meals, all of which boosted the energy of farm workers and helped promote solidarity among them. A distinctively Korean tradition, makgeolli is indispensable for studying and understanding the culinary culture of Korea. Makgeolli is entrenched as a popular alcoholic beverage in contemporary Korean society as well.

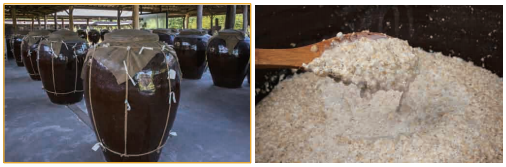

Left: Traditional liquor being fermented in clay jars

Right: The grain mash from which Makgeolli, a milky rice beer, is produced

Nuruk, the fermentation starter for Korean traditional liquor,

is made from a local Korean species of wheat.

It is interesting to note that there has been an increasing inflow of younger people into the production of makgeolli. These young brewers are carrying out diverse experiments with its alcoholic content and the design of the bottles. Such efforts have resulted in diversifying the varieties of available makgeolli products in the market, including high-end versions sold at higher prices. All of these changes represent the creative adaptation of this time-old tradition in response to sociocultural transformations.

Three Liquor-making Traditions Collectively Registered

Before the designation of makgeolli, three more variants of traditional Korean alcohol had been registered on the national intangible heritage list. They are munbaeju (wild pear liquor), Myeoncheon dugyeonju (azalea liquor from Myeoncheon), and Gyeongju Gyodong beopju (authorized liquor from Gyo-dong, Gyeongju), which were collectively designated in November 1986 under the name Local Liquor-making.

Millet and sorghum, the grains of choice for making munbaeju

A Grain Liquor with a Pear Scent

Munbaeju, literally “wild pear liquor,” gained its name from its scent reminiscent of the wild pears native to Korea. Although made purely from grains, munbaeju imparts a distinctive flavor resembling the wild pears known as munbae. The production of munbaeju involves a long and complex process. The two most significant steps in its journey are the making of a fermentation starter and the distillation. The fermentation starter for munbaeju is created with wheat as the starchy source; it is the most significant ingredient in determining the flavor of this traditional liquor. Millet and sorghum are the grains of choice for munbaeju. The clear liquid made from the fermentation of these grains is gently boiled in a cauldron, which is topped by a two- story still known as a soju gori. The gap between the cauldron and the condenser is tightly sealed with rice or wheat dough. The resulting liquor has a yellowish or brownish tinge and gives off a wild pear scent. It is recommended that munbaeju be consumed after six to 12 months of aging. This wild pear-scented liquor reaches 48 ABV, allowing extended preservation.

Myeoncheon dugyeonju, or “azalea liquor from Myeoncheon,”

is brewed with the petals of azalea flowers, a harbinger of spring