Feature

Chuseok, the Korean Autumn Harvest Festival

By Text by Sun Jeong-gyu

The 15th day of the eighth lunar month marks the Korean harvest festival known as Chuseok. This year, it falls on September 10 in the Gregorian calendar. Chuseok is the major traditional holiday among the Korean people along with Seollal (Lunar New Year), and is celebrated through a three-day legal holiday including the days immediately before and after. This year, the holiday period spans four days since the day after Chuseok is Sunday (already a legal holiday) and the Chuseok holiday accordingly skips to the next day.

Chuseok occurs in a season of abundance. Ripening crops are awaiting harvest in the pleasant autumn weather. The traditional Korean saying “I wish things were neither no less nor no more, but were always like Hangawi” (the Korean word for Chuseok) illustrates the link between Chuseok and a sense of plenty that is found in the minds of Korean people. In traditional Korean society, the moon was the major reference for telling the passage of time and for scheduling important steps in farming. The waxing and waning of the moon was also perceived as a mysterious phenomenon connected to the principles of life and death. Full moons were celebrated through diverse seasonal customs, one of which we call Chuseok today.

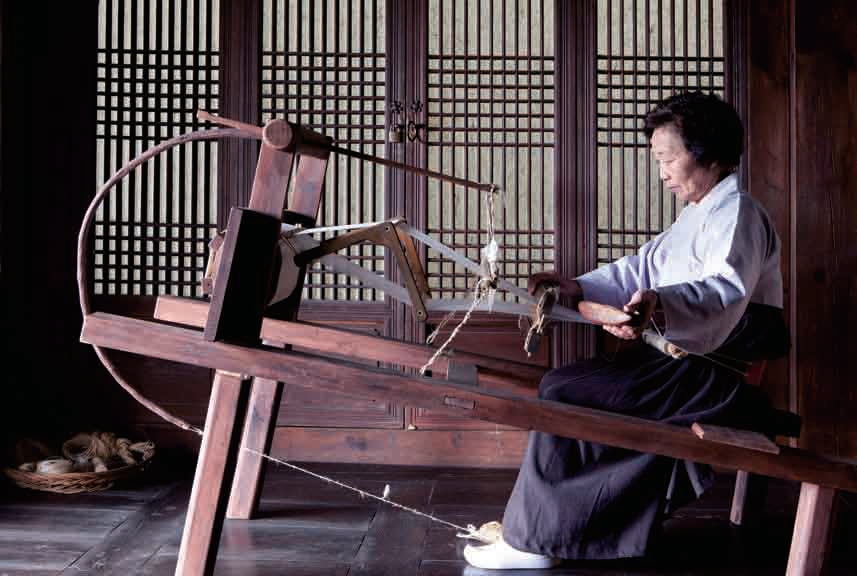

Another name for the Korean harvest festival is Hangawi, a term of pure Korean etymology. Hangawi consists of two parts, han (“great”) and gawi, which is a transformation of gabae, a word with a historical reference. The Korean history Samguk sagi (Records of the Three Kingdoms) accounts that women in the capital of Silla were separated into two teams that squared off against each other in weaving competitions during the gabae holiday. It is recorded that the weaving competitions began on the 16th day of the seventh lunar month and continued for a month. The weaving contest culminated in a festival on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month, where the losing team treated the winners with food and drinks and immersed themselves in a jubilant atmosphere accompanied by dance and music. This historical record indicates that the autumn harvest festival was practiced as a huge celebration lasting a full month. According to the historical document Goryeosa (History of Goryeo), people during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) celebrated the full moon day of the eighth lunar month. They observed rites for ancestors, visited their graves, threw a party while appreciating the full moon, composed poems, and exchanged gifts.

In the Joseon era (1392–1910), Chuseok became fully established as one of the three most significant seasonal holidays along with Seollal and Dano (the fifth day of the fifth lunar month). Ancestral rites at home (charye) and graveyard ceremonies (seongmyo) gained added importance as Chuseok customs. The new dynasty of Joseon adopted Confucianism as its governing philosophy and exalted ancestor worship, a system of beliefs centering around the power held by the spirits of dead ancestors over the fortunes of their descendants. While preparing ritual foods and offering them to ancestors at home and at their graveyards, people in Joseon prayed for happiness and prosperity.

Ritual foods are prepared for ancestors on Chuseok.

It is customary to wear hanbok (traditional Korean clothing) on Chuseok.

Although greatly differing in practices, the 15th day of the eighth lunar month is also celebrated in neighboring China and Japan. This autumn holiday is known as the Mid- Autumn Festival and Jugoya in China and Japan, respectively. Seasonal social practices become established as a national holiday only having gone through a complex development process involving the participation and recognition of a majority of a given social group. This means it is not really possible to choose one specific point in time as the start of today’s national holidays. In the case of China, Li Bai and other poets from the Tang Dynasty (618–907) composed a number of poems featuring the moon as the main subject. However, the Mid-Autumn Festival was only rarely recorded in documents from the time. The practice of celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival was documented in detail in the Song Dynasty (960–1279), and this autumn event was designated as a national holiday by imperial law.

Ganggangsullae, a circle dance performed by women to pray for a bountiful harvest

In Japan, the celebration of the 15th day of the eighth lunar month centers around tsukimi, or “moon-viewing.” Gazing at the full moon, people give thanks for the crops they harvest. This moon-viewing tradition dates back to the Heian period (859–877), when nobles took boat rides to appreciate the moon. Their cruises were accompanied by alcohol, music, and poetry. Rather than looking up at the moon in the sky, they preferred to view its reflection in the river or in a wine cup they held. This sophisticated practice reserved for the nobility was later popularized among the common people during the Edo period (1603–1867) while being transformed into an event celebrating the harvest. Japanese people long considered the moon as a symbol of immortality. They delivered their thanks for an abundant crop and prayed for health to this representation of endless life.

It can be edifying to compare Chuseok to China’s Mid-Autumn Festival. Geographically neighbors, Korea and China have long exchanged cultural influences and there is a great deal of affinity between the two cultures. However, the two countries have undergone distinctive social, cultural, and political development processes that have spurred differences in the practice of cultural traditions. The same applies to theirA autumn festivals.

Ancestor worship stands at the center of celebrating Chuseok, as evidenced by the major position of at-home ancestral rites and graveyard visits among the Chuseok customs. Koreans regard a bountiful crop as a blessing from their ancestors and observe rites for them at home and at their graves as a token of their gratitude. Meanwhile, the Mid-Autumn Festival is rooted in the veneration of the moon and, therefore, is mainly celebrated by moon-viewing. The tale of Chang’e, a popular Chinese myth, relates to moon worship. Chang’e stole the elixir of immortality from her husband, the legendary archer Hou Yi, and escaped to the moon where she became a goddess. This story is derived from the practice of venerating Chang’e as a personification of the moon.

Appreciating the moon and writing poetic songs about their feelings was the major way the literati celebrated the Mid-Autumn Festival in traditional Chinese society. In Korea, there were some men of letters who imitated their counterparts in China and took up moon- viewing accompanied by poetry writing. This was limited to just a portion of the literati class in Korea, however, and never developed into a widespread practice.

The autumn harvest festivals of the two countries share the function of bringing family members together. Married women visit their natal families as well. In China, the Mid- Autumn Festival is also known as “the day of family reunion.” This name refers to the custom of married women gathering with their birth parents for the Mid-Autumn Festival, a practice dating back to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

Korean half-moon-shaped cakes, or songpyeon

Chinese yuebing (“mooncakes”)

Both countries have the custom of eating cakes recalling the shape of the moon during their autumn festivals. The definitive food of the Chuseok holiday is a half-moon-shaped cake called songpyeon. To make songpyeon cakes, rice powder is mixed with water and the resulting dough is separated into half-moon-shaped chunks and stuffed with a filling of soybeans, chestnuts, or jujubes. The songpyeon cakes are then steamed. It is believed that the songpyeon-eating practice on Chuseok was initiated during the Joseon era. The Chinese counterpart of songpyeon is yuebing, or “mooncakes,” a form of pastry dating back to the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279). Mooncakes were originally used as an offering to the deity in the moon. Watching the moon while eating mooncakes is a popular custom widely practiced across China during the Mid-Autumn Festival. These pastry cakes in the shape of a full moon are offered as a gift to relatives and friends on the holiday.

National holidays play a major role in bringing members of a nation together. By commemorating specific days within the year with similar forms of celebration, they nurture a shared consciousness and strengthen national identity. In Korea, Chuseok started off as a weaving contest for women during the Silla period and evolved through the Goryeo and Joseon eras into an arena for the commemoration of ancestors in the present.

Although ancestral worship holds symbolic significance within the celebration of Chuseok, for contemporary Koreans the autumn harvest festival is fundamentally about going home and reuniting with family. Koreans compete fiercely for train tickets to their hometowns long before the start of a Chuseok holiday. They do not mind spending long hours on the road in a massive traffic jam if it means going home for the holiday. On Chuseok, Koreans go back to the place where their parents live, where they were brought up, and where their memories with siblings and friends remain. For Koreans today, it is a way of reconfirming who they are and rejuvenating their body and mind. Chuseok remains as a strong seasonal tradition in today’s Korea.

The ramie-weaving tradition of the Hansan area in South Korea has been registered on the UNESCO intangible heritage list.