Feature

Do You Know Gwangdae?

By Son Tae-do

ⓒ Suwon Cultural Foundation; collected at the Bibliothèque nationale de France

Korea boasts a splendid repertoire of traditional forms of performance, including pansori (an oral tradition often compared to Western operas), farmers’ instrumental music, tightrope walking, and mask-dance dramas. There is instrumental music as well involving the piri (a small double-reed pipe), daegeum (a bamboo transverse flute), gayageum (a twelve-string zither), or haegeum (a double-string zither). All of these entertainments required professional performers, or gwangdae in Korean. Gwangdae was a collective name given to all those who engaged in professional performances in traditional Korean society. They were also known as changu or jaein. These entertainers have long been at the heart of the transmission of Korean performances.

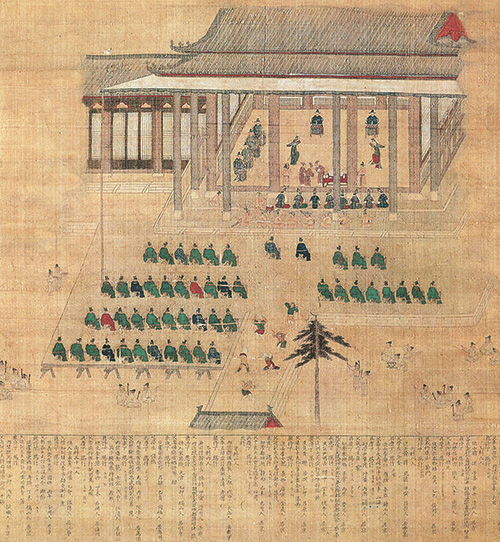

This painting dated to 1580 shows a royal feast held for successful candidates

in the civil service examination. It features gwangdae entertainers putting

on a celebratory performance.

Sandaehui and Gwangdae

The traditional Chinese texts Liezi and Chu Ci describe three sacred mountains floating in the sea on the back of a vast turtle, namely Mt. Penglai, Mt. Fangzhang, and Mt. Yingzhou. When peace reigns supreme, this mountain-supporting sea creature was believed to perform a dance. This legend was widely disseminated across East Asia and inspired a common performance tradition. When there was cause to celebrate in China and other East Asian states, structures were built in the shape of a mountain and music, dance, theater, acrobatics, and martial arts were performed on and around these structures. It was designed to reference the dancing of the legendary turtle. This entertainment tradition of offering a variety of performances on a mountain-shaped stage was called sandaehui, or “entertainment on a mountain-like stage.”

This all-inclusive form of entertainment involving a mountain-shaped structure was introduced to Korea no later than 572 during the reign of King Jinheung of Silla, and was actively practiced all the way through the Goryeo era (918–1392). During this period it was held at state-level Buddhist ceremonies such as Yeondeunghoe (Lantern-lighting Festival) and Palgwanhoe (Festival of the Eight Vows) and on the occasion of the arrival of foreign envoys. During the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), sandaehui were practiced at times of major state celebrations and diplomatic visits from China. As they were considered an integral part of welcoming Chinese emissaries, sandaehui continued to be practiced into the later years of the Joseon era.

Men serving at the post stations (yeokjol), entertainers (changu) and butchers (baekjeong) should be liberated from their social status as the lowest caste.

From the entry into the Gojong sillok (Annals of King Gojong) on July 2, 1894

These state-affiliated entertainers normally took on the role of playing musical instruments for government agencies and, when an occasion arose, could serve as singers, dancers, actors, or acrobats. The size of this hereditary occupational group gradually increased through intraclass marriage until reaching the tens of thousands toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty. Hereditary gwangdae entertainers had no possibility of climbing the social ladder and no right to own land. This professional entertainer group was allowed to do nothing but perform.

Celebrations for New Civil Servants

During the Goryeo and Joseon periods, membership in the political leadership of Korea was determined by state examinations. Similar merit-based institutions were also in place in China from 587 to 1904 and in Vietnam from 1034 to 1888. In Korea, those who passed the civil service examination were provided a series of celebrations—a royal banquet at the palace (eunyeongyeon), a street parade lasting for three to five days (yuga), municipal-level festivities in their hometowns (yeongchinyeon), and parties in their individual households (muhuiyeon). All these events needed gwangdae to complete the celebration. These events began with the introduction of the civil service examination in 958 and persisted until the examinations were abolished in 1894 in Korea.

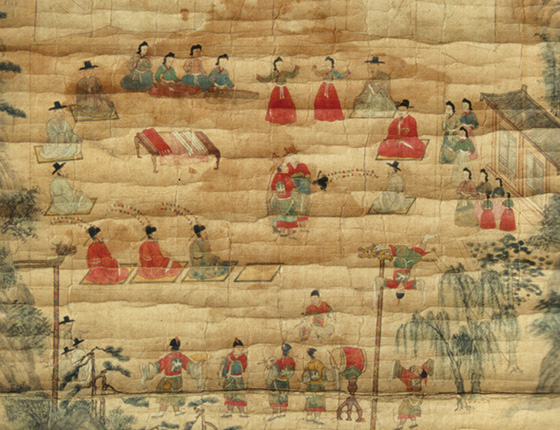

This painting produced in 1693 shows a household party held by the Joseon scholar

Gwon Yang for his sons who had successively passed the civil service examination.

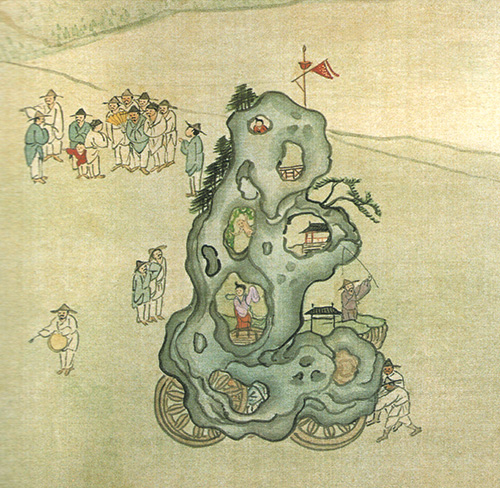

This Buddhist painting at Heungguksa Temple dated to 1868 portrays

a tightrope artist walking double ropes, one of the regular performances included

in a sandaehui event during the late Joseon period.

The civil service examination was held every three years. On top of these regular events, irregular examinations were organized to celebrate important state occasions. It is estimated that irregular examinations were held every nine months during the Joseon era. During the Goryeo Dynasty, each examination selected 33 civil officials and 28 military officials. Another component was added to the existing examination system for low-level civil officials in the Joseon era to allow two new types—classics licentiates (saengwon) and literary licentiates (jinsa). One hundred candidates were selected for each category. This expanded the number of civil servants produced from each regular and full-scale irregular examination (jeunggwangsi) to around 260. If five entertainers were required to fete each successful candidate, simple math indicates that more than 1,000 of them were needed. Moreover, the number of military officials selected greatly increased from the previous 33 to hundreds and sometimes even thousands or tens of thousands toward the end of the Joseon Dynasty.

As celebrations for passing the exam were held not only in the capital but also in the candidates’ hometowns, the entire nation became immersed in a festive mood. In particular, the celebration held in individual households usually lasted for several days and nights and provided a venue for various performances. One of the most popular types of entertainment featured in this days-long household party was pansori, a form of narrative song performed for several hours by a vocalist to the accompaniment of a double-headed barrel drum. Open to people of all classes, these household celebrations led to the development of the pansori epic chant into a popular but sophisticated form of performing art. During the Joseon era pansori was enjoyed by all status groups from the royalty to commoners.

Sandae, or “mountain-like stage,” came in diverse sizes in either a mobile or fixed form.

The one shown in this picture is a small mobile sandae.

The Donghak Movement and Gwangdae

Korean peasants took up arms in 1894 inspired by the spirit of Donghak (Eastern Learning), a new religion founded in 1860 with opposition to Western culture and a belief in the equality of all people at its theological center. During the uprising by the Donghak peasant army that began in Jeolla-do Province, the gwangdae aligned themselves with both sides of the rebellion. With their employment based on their affiliation with the government, some joined the government troops sent to suppress the Donghak rebels. On the other hand, there were many in this low-status group who deeply sympathized with the Donghak tenets, particularly its principle of equality, and became deeply involved in the rebellion. In the initial phase of the Donghak movement, gwangdae served as combat soldiers both in the government forces and the rebel army, as seen in the following:

The military officers Yi Jae-seop and Song Bong-ho marched toward Gobu, Jeolla-do Province with a 1,000-strong force under their command. These newly drafted soldiers were all of mubu (husbands of shamans) status.

From pages 141–143 in the book The History of Donghak written by Oh Ji-yeong and annotated by Lee Jang-hui

FThe Donghak leader Kim Gae-nam organized a military unit with more than 1,000 changu and jaein recruited from Jeolla-do Province and treated them with respect in an effort to get the best out of them.

From page 23 in the third manuscript of the early modern history Ohagimun by Hwang Hyeon

FThe Donghak leader Son Hwa-jung selected jaein and formed a unit, asking Hong Nak-gwan to lead them. Under the supreme command of Son Hwa-jung, Hong Nak-gwan, a jaein from Gochang, Jeolla-do Province, had thousands of nimble and belligerent soldiers following his leadership. Although usually considered comparable to the troops under Jeon Bong-jun and Kim Gae-nam, Hong’s unit was in fact the best.

From page 35 of the third manuscript of the early-modern history Ohagimun by Hwang Hyeon

Given the records above, it appears there were thousands of gwangdae in Jeolla-do Province alone at the time of the Donghak movement. It seems that their numbers totaled in at least the tens of thousands nationwide. As the movement progressed, gwangdae increasingly sided with the rebels. Among the three commanders immediately under head commander Jeon Bong-jun (namely, Kim Gae-nam, Son Hwa-jung, and Hong Gye-gwan), Hong Gye-gwan was of gwangdae status. As seen above, his brother Hong Nak-gwan was the leader of an elite gwangdae combat unit.

Korea might be unique in the globe in having maintained such large numbers of professional entertainers as a particular social class until the early-modern period. The survival of these professional entertainers nurtured the advancement of Korean performing traditions. The reforms of 1894 liberated the gwangdae from their low social status. However, many of them remained in their traditional profession and continued giving performances. It should come as no surprise that many of the senior masters of traditional performance in the present are of gwangdae descent. The stories of Joseon professional entertainers are still highly relevant for understanding today’s performances.

Text by Son Tae-do, Hoseo University

Photos by Son Tae-do, and Suwon Cultural Foundation

한국의 ‘광대’를 아십니까?

한국의 민속예능들은 세계적 차원에서도 그 수준들이 높은 편이다. 서양의 오페라에 비견되는 수준 높은 성악예술로서의 판소리를 우선 들 수 있고, 농악들도 대단하며, 줄타기 기술들도 그러하며, 각종 가면극들도 사실상 수준들이 높다. 피리, 대금, 가야금, 해금 등 각종 악기연주들도 분명 주목할 만한 것들이다. 이러한 한국의 각종 민속예능의 중심에는 한국의 ‘광대(廣大)’가 있다.

동아시아의 산대희와 한국의 광대

오래된 중국의 전설에 따르면, ‘동해바다에 봉래(蓬萊), 방장(方丈), 영주(瀛洲)와 같은 삼신산(三神山)이 있고, 이들을 큰 거북이가 떠받치고 있는데, 국가가 태평하면 이 거북이가 춤을 춘다’(『열자(列子)』: 굴원, <초사(楚辭)>)는 것이다. 이에 전통시대 중국을 비롯한 동아시아 각국들은 국가에 큰경사가 있으면, 봉래, 방장, 영주와 같은 삼신산을 만들고 그 위와 아래에서 가무백희를 했다. 그 큰 거북이가 춤을 추는 것을 형상화한 것이다. 이것이 바로 동아시아의 산대희 문화다.

이러한 산대희를 한국의 경우에도 적어도 신라 진흥왕 때(왕 33년. 572)부터는 해 왔고, 신라를 이은 고려에서는 매년 연등회(2월 15일)와 팔관회(11월 15일) 같은 국가적 행사들에 산대희를 해 왔다. 조선시대에도 국내의 큰경사나 중국사신이 올 때 이뤄졌다. 특히 조선시대에는 중국사신이 올 때 으레 이 산대희를 갖추어야 했기에, 산대희에 대한 여러 일들이 조선시대 말까지 유지되었다.

그런데 이러한 산대희는 좌우 산대를 갖추고 조선 중기의 경우 600명 정도의 광대들이 동원되는 행사였기에, 한국에서는 국가적 차원에서 이 광대들을 확보하고 있을 수밖에 없었다. 한국에서는 민간에서 이러한 산대희에 동원할 만한 예능집단이 없었기 때문이다. 반면 중국에서는 민간에서도 이러한 산대희에 동원할 만한 예능인들이 많았기에, 송나라 효종 2년(1164)에 국가에서 장악하고 있던 악호(樂戶)를 해방시켰다.(안상복, 「송‧금대 잡극 원본 연구」, 28쪽) 중국사신의 왕래가 없었던 일본에서는 이미 782년에 산악호(散樂戶)를 해방시켰다.(河竹繁俊 저, 이응수 역, 『일본연극사(상)』, 162쪽) 반면 한국에서는 다음처럼 1894년 근대 무렵에 와서야 ‘창우(倡優)’ 곧 ‘광대’라는 하나의 천민 신분집단을 해방시켰다.

역졸(驛卒), 창우(倡優), 백정(白丁)들 모두 천인의 신분을 면해 줄 일

『고종실록』, 31년(1894) 7월 2일

이것이 바로 근대 무렵까지도 하나의 신분집단으로 수만 명의 광대들이 한국에 있게 된 이유다. 이들은 평소에는 관아의 악공들로 있다가 유사시에는 광대로도 활동한 한국의 악공‧광대집단 곧 광대집단 사람들이었다. 이들은 같은 신분의 사람들끼리만 혼인하는 전통사회의 계급내혼(階級內婚)을 통해 그 수가 많아져 근대 무렵 수만 명에까지 이르게 된 것이다. 이들 광대들은 사실상 토지를 가지지 못하고 오직 민속예능만을 하며 살아간 사람들이었다.

과거제도와 광대

중세시대 때 신분에 의하지 않고 과거(科擧)와 같은 시험을 통해 지배층을 형성시킨 나라는 중국(587~1904), 한국(958~1894), 월남(1034~1888) 세 나라밖에 없었다. 그런데 이러한 과거(科擧)에는 급제자를 위한 축하행사들이 으레 수반되었다. 궁궐에서의 잔치인 은영연(恩榮宴), 길에서 이뤄지는 일종의 퍼레이드(prade)인 3~5일 간의 유가(遊街), 지방관아에서의 영친연(榮親宴), 급제자의 집에서 이뤄지는 문희연(聞喜宴) 등이 그러한 것들이다. 그리고 이러한 행사들에는 축하 분위기를 돋우기 위해 으레 광대들이 동원되었다. 한국에서는 고려 광종 때인 958년에 과거가 시작되어 1894년까지 천 년 가까이 이러한 과거가 이뤄졌다.

과거는 3년마다 정기적으로 이뤄지는 식년시(式年試) 외에 각종 별시들이 이뤄졌는데, 조선시대의 경우 이러한 별시는 통계적으로 9개월에 한 번씩 이뤄졌다. 또한 문과 33명, 무과 28명 정도를 뽑았던 고려시대와 달리 조선시대에는 종래의 문‧무과를 뽑는 대과 외에도 생원 100명, 진사 100명을 뽑는 소과도 있어 식년시와 별시 중 증광시(增廣試)에는 260명 정도의 급제자 등이 나왔다. 이때 나온 260명 정도의 급제자 등에게 5명 정도의 악공‧광대만 배정하더라도 천여 명 이상의 악공‧광대들이 필요했다. 특히 조선 후기에 들어서는 문과는 33명을 유지했으나, 무과의 경우는 종래의 28명이 아니라 흔히 수백 명을 뽑았고, 수천 명을 뽑기도 했으며, 어떤 때는 수만 명을 뽑기도 했다.(이성무, 『한국의 과거제도』, 157~161쪽)

한편 과거 급제자 등의 축하행사는 과거가 이뤄지는 서울에서뿐 아니라 급제자 등이 사는 곳의 지방관아와 집에서도 이뤄지던 것이기에 또한 전국적으로 이뤄졌다. 특히 급제자 등의 집에서 이뤄지는 문희연과 같은 경우는 며칠에 걸쳐 흔히 밤을 새워 이뤄졌기에, 광대의 여러 놀음들이 발전할 수 있었다. 그 중 조선 후기에는 장시간 공연물이었던 판소리가 특히 각광을 받았는데, 판소리는 아닌 말로 위로는 임금으로부터 아래로는 일반 서민들까지 모두 즐기는 이른바 대중적이면서도 고급 성악예술로 발전했다. 급제자 등의 행사에는 으레 상‧하층이 모두 참가했기 때문이다.

한국의 동학농민혁명과 광대

1894년 한국에서 동학농민혁명이 일어났을 때, 광대들의 운명은 일단 두 편으로 갈리었다. 이들은 기본적으로 관(官)해 속한 악공‧광대집단이었기에, 이들의 일부는 진압군인 관군이 되었다. 한편 이들은 천민들로 사람을 하늘과 같이 여기며 신분을 가리지 않는 동학에 깊이 감동되어 있었기에, 동학에도 많이 관여했다. 그래서 동학농민혁명이 처음으로 일어났을 때는 다음처럼 이들 광대들은 관군이나 동학농민혁명군에나 모두 주전투부대로 등장했다.

부관 이재섭(李宰燮)과 동 송봉호(宋鳳浩) 등이 1천 명의 병정을 거느리고 고부로 행군령을 내렸다. 당시 새로 뽑은 병정은 모두 무부(巫夫) 출신이라

(오지영 저, 이장희 교주, 『동학사』, 141~143쪽)

처음에 김개남은 도내의 창우(倡優)·재인(才人) 천여 명으로 일군(一軍)을 만들어 그들을 두터이 예우해서 그들의 사력(死力)을 얻음을 도모했다.

(황현, 『오하기문』, 제3필 23쪽)

처음에 손화중은 도내의 재인(才人)을 뽑아 1포를 조직하고 홍낙관(洪樂官)으로 하여금 이를 지휘하도록 하였다. 홍낙관은 고창의 재인으로서 손화중에 속하여 그 부하 수천 인이 민첩하고 정예였으므로 손화중이 비록 전봉준, 김개남과 정족지세(鼎足之勢)에 있었다 할지라도 실제로는 최강이었다.

(황현, 『오하기문』, 제3필 35쪽)

관군에도 1천 명, 동학군들에도 천여 명, 수천 명의 광대들로 된 부대들이 있었으니, 동학농민혁명 기간 전라도에만 하더라도 이른바 수천 명 이상의 광대들이 있었다. 그러므로 그 당시 전국적으로는 적어도 수만 명의 광대들이 있었던 것이다. 이들을 ‘창우’, ‘재인’ 곧 광대라고 하는 것 외에 ‘무부’라 하기도 한 것은 국가에서는 고려 말 이래 무당집안의 남자들을 모두 모아 악공 곧 악공‧광대집단으로 하여 왔기 때문이다.(『고려사』, 열전 ‘정도전’) 이후 동학농민혁명이 기간 광대들은 주로 동학군으로 활동했다. 동학군의 우두머리였던 전봉준 아래의 3대 두령인 김개남, 손화중, 홍계관 중 홍계관이 광대 출신이었고, 홍계관의 형이었던 홍낙관은, 위에서 보았듯, 손화중 부대의 최강 전투부터 광대부대 대장이었기 때문이다.

고대나 중세가 아닌 근대까지도 하나의 신분집단으로 수만 명의 ‘광대’와 같은 전문 예능집단이 있었던 나라는 한국이 유일할 것이다. 그래서, 앞서도 말했듯, 한국의 민속예능들이 대체로 그 수준이 높은 편이다. 그리고 이들은 1894년 ‘창우’ 곧 ‘광대’ 신분에서 해방되었지만, 그들 중 상당수는 여전히 민속예능 영역에 남았다. 그래서 오늘날에도 한국의 민속예능 영역의 원로들은 상당수가 여전히 이들 광대집안 후손들인 것이다. 오늘날 한국의 민속예능을 이해하는 데도 이러한 한국의 광대에 대한 이해가 여전히 중요하다 할 수 있다.

Text by 손태도, 호서대학교 교수

Photos by 손태도, 수원문화재단