Feature

Moon Jars:

Self-restraint in Porcelain

By Kim Hyun-jung

Moon jar; collected at the National Museum of Korea; Photo by Koo Bohnchang

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), the stateliness of the royal court and the dignity of the literati were expressed in their related artworks, particularly so in white porcelain. The white porcelain produced in the 17th–18th centuries reflects a cultural renaissance in Joseon society. At the time, Joseon was recovering from the social, political, and economic damage of two rounds of foreign invasion, first by the Japanese (1592–8) and then by the Manchu (1636–7). A period of cultural florescence soon followed.

A Sense of Generosity and Simplicity

Moon jar; collected at the National Museum of Korea

Joseon adopted Confucianism as its governing philosophy, accentuating particularly the focus on the Confucian virtue of ye (li in Chinese, or “propriety”). The Analects of Confucius, one of the main Confucian classics, states that propriety is a vehicle for practicing benevolence (in in Korean and ren in Chinese), while benevolence means restraining oneself and recovering propriety.

For the purpose of maintaining propriety, Confucian scholars in Joseon were required to suppress or moderate any expression of selfish desires or emotions. The Joseon literati supported moral uprightness, pursued simplicity in life, and sought satisfaction in what they already possessed. All of these virtuous qualities prized by Joseon scholars were inherent in the aesthetics of white porcelain.

White porcelain was a technical advancement emerging out of celadon, the previous dominant type of pottery. A highly refined iron-free clay body was shaped into a desired form and fired at temperatures exceeding 1,250 degrees Celsius. It quickly became the pottery of choice for the Joseon court. To ensure a stable supply of royal wares, a government kiln was installed in Gwangju in Gyeonggi-do Province, an area near the capital that offered a favorable environment for porcelain production due to its abundant supply of firewood and quality clay. After the transfer of the site of the royal kilns several times within the Gwangju area seeking better access to firewood, it settled at what is now Bunwon-ri in Gwangju in 1752.

The two rounds of foreign invasions over the late 16th–early 17th century inevitably impacted the production of white porcelain. Its pure white turned more grayish, and blue decoration was replaced with iron when the import of cobalt was disrupted. By the late 17th century, however, stability was being restored and, in turn, porcelain came to recover pure white tones. With white porcelain being produced in abundance for both the royal court and the literati class, the crafting of white porcelain bloomed once again in Joseon. One of the most popular motifs for porcelain among the literati was the “four gentlemen,” specifically referring to the plum tree, orchid, chrysanthemum, and bamboo, all symbols of the dignity and integrity of Confucian scholars.

Moon Jars Displaying the Essence of White Porcelain

Moon jar; collected at the National Museum of Korea

Among the many varieties of white porcelain fashioned at the Joseon royal kilns was a type known as “moon jars.” In vogue from the late 17th to the mid-18th centuries, this type of white porcelain with a round body swollen around the middle was nicknamed “moon jars” during the 1950s based on its appearance. Acclaimed as the epitome of Joseon white porcelain, moon jars showcase the virtues of restraint and simplicity through their pure white color and round form. This is a unique quality of Korean moon jars with no clear parallel in the pottery of China or Japan.

As its name suggests, white porcelain is characterized by a white surface, either plain or decorated with motifs painted in cobalt, iron, or copper. The white can appear in diverse shades of milky, snowy, grayish, and greenish white.

A whiteness resembling milk is considered the definitive baseline color for moon jars. However, no jar shows the exact same milky tone across its entire surface. Some areas may be brownish from incomplete combustion or oxidization, while others may exhibit colored stains due to penetration by the liquid contained inside. These color variations can blend into the overall whiteness of the surface to create a pleasant visual sensation. They also generate a sensation of warmth across the cold porcelain surface of the jars.

Moon jar; collected at the National Museum of Korea

Moon jar; collected at the National Museum of Korea

A Sense of Generosity and Simplicity

The appeal of moon jars is derived from their bounteous form and simple silhouette. Normally reaching as high as 40 centimeters or more, the widest diameter equals the height. Moon jars are broadly round, but do not present a symmetrical globe. This denial of symmetry adds a subtle variation to the stable outline of a moon jar, creating a feeling of naturalness.

It was not a usual practice to leave a ceramic vessel as large as a moon jar undecorated. Their extensive white surface can appear like an empty canvas calling to be filled. However, moon jars forego decoration and retain their pure white surface. This must not have been possible without considerable exercise of restraint of the natural impulse to add decorative patterns to the surface.

The moon shines on all of us, but there are no two people who see the same moon. Likewise, when people observe a moon jar different thoughts and feelings are aroused. The unique beauty embodied in moon jars that was completed through the virtue of self-restraint represents a high point in Joseon aesthetics and provides a continuous source of artistic inspiration for the present.

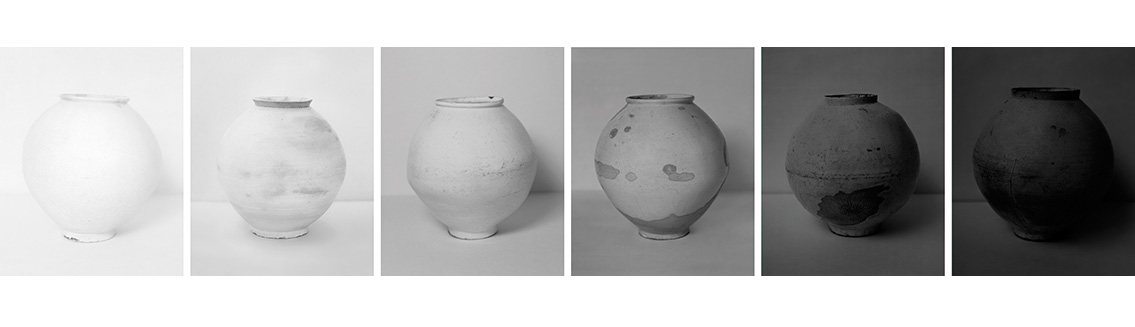

A collage of moon jars entitled Moon Rising II featuring (from the left) examples collected at the National Museum of Korea (Seoul), Musée Guimet (Paris), Museum of Oriental Ceramics (Osaka), Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art (Seoul), and two from the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (Tokyo); Photos by Koo Bohnchang

Moon jar; collected at the British Museum Photo by Koo Bohnchang

Text by Kim Hyun-jung, Jeonju National Museum of Korea

Photos by Koo Bohnchang and National Museum of Korea

절제미의 승화, 순백의 조선백자, 달항아리

조선시대에는 유교를 근간으로 왕실의 품위와 선비의 격조가 미술품에 유감없이 발휘되었다. 문기(文氣)가 흐르는 품위와 격조는 조선 백자의 미적 특성이기도 하다. 17~18세기 영·정조 연간에 제작된 조선 백자도 예외는 아니었다. 이 시기에 조선은 왜란(1592~1598)과 호란(1636~1637)의 피해를 극복하여 정치·사회·경제적으로 안정과 번영을 회복하였으며, 문화적으로는 조선의 제2의 황금기를 이루었다.

조선의 이상과 세계관을 담은 백자

조선은 ‘예(禮)’를 중시하는 유교 사회였다. ‘예’란 유교 문화 전통에서 인간 도덕성에 근거하는 사회질서의 규범과 행동이자 유교 의례의 구성과 절차였다. 『논어』에 따르면, 공자는 ‘예’는 ‘인(仁)’의 실천방법으로서 ‘’인’은 자신의 사욕을 극복하고 ‘예’를 회복하는 것’이라고 가르쳤다.

‘예’를 실천하기 위해 선비들이 사욕을 극복하는 데 필요한 것은 ‘절제’였다. 절제란 사람이 욕망이나 감정 표현 따위가 정도를 넘지 않도록 알맞게 조절하거나 제어하는 것이다. 선비들은 자신의 내적인 청결함을 중시하고 담박한 생활을 지향하였으며, 나아가 자연과 더불어 안분지족하는 삶을 추구하였다. 담박함이란 사람의 성품에 사사로운 욕심이 없고 순박한 것을 뜻한다. 백자에는 조선시대 선비들이 추구하는 절제와 청결, 담박함, 그리고 안분지족의 삶이 고스란히 담겨 있다.

백자는 청자보다 기술적으로 한층 진보된 자기다. 철의 함량이 전혀 없이 깨끗하게 정선된 태토로 성형된 후 청자보다 높은 온도인 1250도 이상에서 번조된다. 이때 가마 내 불의 온도를 높이려면 많은 땔감이 필요했다. 조선 왕실은 조선 초에 백자를 왕실의 자기로 선택했다. 그리고 백토와 땔감이 많아 백자 생산에 적합한 경기도 광주에 국영 공장인 관요(官窯)를 설치하고 백자를 제작했다. 그러다가 영조 28년(1752) 현재의 광주군 남종면 분원리에 관요의 위치를 고정하고 안정적인 생산을 도모했다.

두 차례의 전란에 따라 백자 생산에 차질이 생기기도 했다. 이 시기 백자의 빛깔은 회백색을 띠게 되었고, 청화의 수입이 차단되어 철화가 대신 사용되었다. 그러나 숙종(재위1674~1720) 조에 사회가 안정되어 가면서 회백색은 다시 백색을 띠게 되었다. 또한 왕실뿐만 아니라 선비들의 취향을 반영한 백자가 제작되면서 다시 조선백자 문화가 활짝 꽃피었다. 청화백자에는 선비의 품격과 덕을 표현하는 매화, 난초, 국화, 대나무 등의 사군자(四君子) 등이 그려졌다.

달항아리의 한결같이 따뜻한 순백색

조선의 관요에서는 순백자, 청화백자, 철화백자, 동화백자 등 다양한 종류의 백자가 제작되었다. 이 가운데 조선후기를 대표하는 것이 바로 ‘백자달항아리’이다. 17세기 후반에 나타나 18세기 중엽까지 유행한 이 백자는 보름달처럼 크고 둥글게 생겼다 하여 1950년대에 백자달항아리라는 이름을 얻었다. 달항아리를 조선 백자의 정수로 꼽는 이유는 절제와 담박함으로 빚어낸 순백의 빛깔과 둥근 조형미에 있다. 이는 중국과 일본의 도자기에서는 찾아 볼 수 없는 조선 달항아리만의 특징이다.

백자의 가장 중요한 특색은 흰색이다. 아무런 장식이 없는 순백자든 청화나 철화로 그려진 그림이 있는 백자든, 바탕을 이루는 백색에 따라 그 느낌이 달라진다. 조선 백자의 흰색은 똑같은 경우가 없이 매우 다양하다. 우윳빛이 나는 것은 유백(乳白), 눈의 흰색과 같은 것은 설백(雪白), 회색빛이 도는 것은 회백(灰白), 푸른 기를 띠는 것은 청백(靑白) 등으로 부른다.

달항아리는 유백색을 기본으로 한다. 그러나 하나의 달항아리조차 완벽하게 동일한 흰색을 지니고 있지는 않다. 불완전하게 연소된 부분이 있거나 산화되어 황색을 띤 흰색 부분도 있다. 어떤 달항아리는 안에 넣어두었던 액체가 스며 나와서 물든 부분도 있다. 그 물든 부분 또한 달항아리 전체의 흰색과 어우러지며 오묘한 빛깔을 자아내기도 한다. 이렇게 하나의 달항아리에도 끊임없이 변화하는 여러 흰색이 존재한다. 흰색이지만 똑같은 흰색이 아니다. 아마도 이것이 싸늘한 자기임에도 한결같이 따사로운 온기가 느껴지는 까닭일 것이다.

달항아리의 너그러운 형태와 담박한 선

달항아리의 오묘함은 너그러운 형태와 담박한 선에서 나타난다. 달항아리는 높이와 몸체의 최대 지름이 거의 같아서 마치 보름달처럼 둥근 몸체를 이루며, 보통 높이가 40cm를 넘는 것이 일반적이다. 원형이라고 모두 같은 대칭의 원형이 아니다. 이러한 형태는 고요하기만 한 듯한 달항아리에 미세한 움직임과 변화를 불러일으킨다. 마치 실제 달과 같이 둥글고 자연스럽고 또 넉넉한 느낌이다.

달항아리처럼 높이가 40cm가 넘는 큰 항아리에 아무런 문양 장식도 하지 않은 것은 유례없이 독특한 일이다. 달항아리의 흰 표면은 마치 빈 공간과 같아서 무엇인가 채워 넣고 싶은 욕망을 불러일으킨다. 그럼에도 불구하고 모든 문양과 장식을 없애고, 결국 표면을 흰색만으로 장식한 것이다. 이는 무엇인가를 채우고 싶은 욕망에 대한 절제 없이는 불가능한 일일 것이다. 달항아리의 미묘하고 진중한 흰색 표면은 사람들에게 다른 생각과 마음의 감흥을 불러일으킨다. 이것은 조선만의 독특한 미감이며 욕심 없는 흰색의 공백이 가져온 아름다움이다.

달은 만인을 비춘다. 같은 달이지만, 달을 바라보는 사람들은 저마다 다른 달을 본다. 이와 마찬가지로, 사람들은 신비로운 백자를 보면서 저마다 다른 아름다움을 발견한다. 절제와 담백함으로 빚어낸 오묘한 순백의 세계가 담긴 백자는 조선시대의 독특한 아름다움을 대표하는 조선미의 정수이다. 또한 과거로부터 현재와 미래에 이르기까지 사람들을 새로운 영감과 창조의 세계로 이끄는 또 다른 문이다.

Text by 김현정 학예연구관(국립전주박물관)

Photos by 구본창, 국립중앙박물관