Feature

Noble Transportation

in Gama

By Chung Yeon-sik

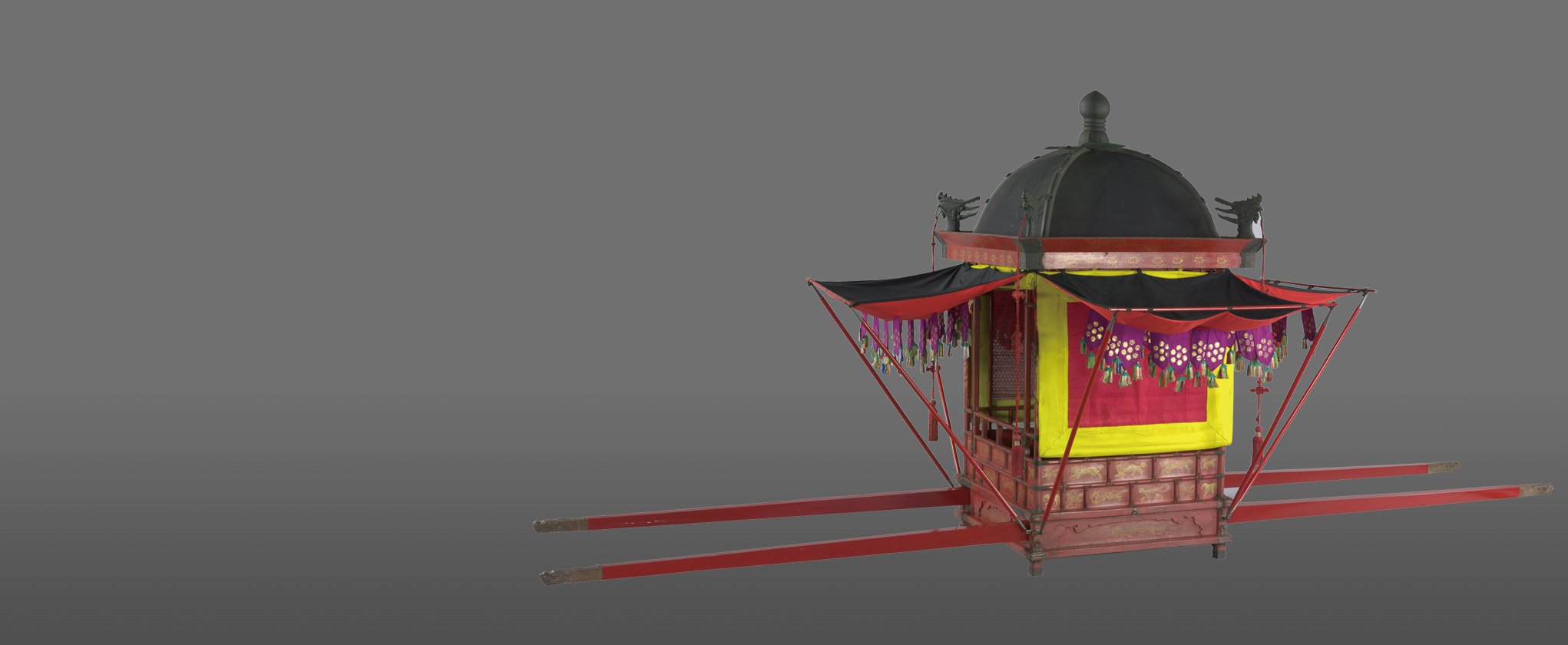

Yeon: This is a royal palanquin reserved for the king, his wife, or a crown prince or princess (collection of the National Palace Museum).

Depicted against a background of the Roman Empire, the movie Ben-Hur features the main character racing in a chariot drawn by four horses. Films set in the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States period of China also highlight horse-powered carts, while Hollywood Westerns frequently show covered wagons drawn by horses or oxen. Carts can be found portrayed in tomb murals from the ancient Korean kingdom of Goguryeo. However, Korea’s mountainous terrain prevented wheeled vehicles from ever becoming a preferred means of transport. Koreans of the past frequently rode on the back a horse or donkey, but they also relied on gama, a Korean type of litter. Gama palanquins did not roll on wheels and were powered by humans rather than animals.

Flamboyant Palanquins for People of Lofty Status

Deong: Lavishly ornamented with motifs of flowers, vines, bats,

and the “seven treasures” (chilbomun) on all sides, the deong is a palanquin used

by royal princesses (collection of the National Palace Museum).

The gama was not an efficient vehicle. As Park Je-ga, a scholar of Practical Learning (Silhak) from the late Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), pointed out in his book Bukagui (Discourse of Northern Learning), a gama required the labor of multiple people for the transportation of just a single one. In the hierarchical Joseon society, however, it was considered improper for a person of high status to be seen on foot. The king, standing at the peak of the social pyramid, walked little even when inside a palace, moving about instead in a small roofless palanquin called a yeo. Outside a royal residence, he rode a horse or took an outdoor palanquin called a yeon. A yeon for the king was lavishly decorated. A dragon-carved column supported each of its four sides, and the enclosed sedan was ringed with beaded curtains and other ornamentation. Each end of the carrying poles was ornamented with a dragon head and the entire palanquin was painted red, a color reserved to the royal family. More carriers meant greater stability and less disturbance to the royal passenger, so around 20 people normally carried a yeon.

State councilors, the highest-ranked Joseon civil servants, moved about in yanggyo. This type of gama was carried by four porters, one each at the sides, front, and back, shouldering straps tied to the support poles. A yanggyo is portrayed in Painting of the Life of Modang Hong I-sang by the 18th century painter Kim Hong-do. In the picture, Hong I-sang, the Second State Councilor, rides on a palanquin at night with a large droopy fan held over him. His assistants clear a path by shouting, followed by the entourage of about 20 people clustered around the palanquin. An intact leopard hide covers the seat of the chair. A leopard tail hanging loose from a palanquin was considered an element of style at the time.

Palanquins with Wheels and Horses

Ssanggyo: Alleungsinyeong, a depiction of the procession of a newly appointed civil servant by Kim Hong-do, features

a ssanggyo. Reserved for civil servants of rank two or above, ssanggyo were driven by horses but balanced by human carriers (collection of the National Museum of Korea).

Yanggyo: In Painting of the Life of Modang Hong I-sang by the 18th-century painter

Kim Hong-do, Hong I-sang is accompanied by a 20-strong entourage while riding in a yanggyo,

a palanquin exclusively for state councilors (collection of the National Museum of Korea).

Equally as flamboyant as yanggyo were ssanggyo. Two long poles were hung lengthwise from the saddle of one horse to the front and one to the rear of the sedan. Two short poles placed at right angles to the longer poles were held by porters at either side to balance the weight between two sides and maintain stability for the noble passenger inside. Ssanggyo were reserved for royal secretaries and ministers of rank two or above. Yanggyo were allowed only outside the city walls of Hanyang for those not of royal descent. Synchronized movement by the two horses was essential to the speed and stability of a yanggyo, so an additional servant walked alongside singing a rhythm that encouraged the horsemen, carriers, and horses to stay in pace.

Another type of palanquin worth mentioning is the choheon, a peculiarly shaped sedan chair that was used by officials of the ministerial level or above. A seat was set high above a single wheel and supported by two long poles. Another pole was fastened across them at the front and back to be gripped by the porters. Invented during the reign of King Sejong (r. 1418–50), the choheon was a unique Korean version of a litter and sparked curiosity among visiting Chinese envoys who would be invited to try one for short distances. In general, though, the most popular kind of palanquin for civil servants was a namyeo, an open chair carried on two long poles and equipped with a stepping board, arm rest, and back support. Namyeo were predominantly ridden by ministers and royal secretaries of advanced age, but were not necessarily reserved for them. The king would sometimes use one for transport within the palace or for short distances outside it. Heads of local governments would ride in them as well. A namyeo could be made simply by just fixing a stepping board and poles to an open seat. It could be made of bamboo or decorated by wrapping kudzu vines at either end of the poles.

Choheon: Distinguished by its peculiar appearance with a seat fixed above a single wheel, a choheon was used by civil servants of the ministerial level or above (collection of the National Palace Museum).

Women’s Palanquin, Inconvenient but Ornate

Starting around the 16th century, Joseon women began to be transported in yuok gyoja. As a palanquin reserved for women, a yuok gyoja was distinguished by its delicate and aesthetic ornamentations. Women of high social status were the most frequent passengers in this type of palanquin, but commoners could ride these gracefully decorated carriages on their wedding days. While ornately decorated, this female sedan chair was never a comfortable means of transportation. The narrow interior could quickly become suffocating on hot summer days, so a servant would follow along fanning the woman inside through a small window. A chamber pot was kept inside for emergencies, and a basket would be ready in case of motion sickness. In the early Joseon era, women rode freely like men in an open palanquin called a pyeonggyoja, or “flat palanquin,” or on horses and donkeys. As Confucian ideals tightened their grip on Joseon society, however, an open palanquin began to be considered problematic as a vehicle for women since it was feared that male carriers might flirt with a female passenger or they might come in contact with her clothes or even a part of her body. Therefore, it was recommended that noblewomen should change their carriage of choice to a closed palanquin, and females of low social status should simply walk or ride horseback.

Saingyo: Literally meaning a “four-man palanquin,” the name derives from it being carried by four carriers. Saingyo were mostly used by women of high status on their weddings and decorated with a design of the 10 traditional symbols of longevity (sipjangsaeng) (collection of the National Palace Museum)

Yuok gyoja: These were used by women of noble descent on outings. Yuok gyoja were heavily decorated with symbolic motifs representing fertility and longevity (collection of the Onyang Folk Museum).

However, the simple and inexpensive pyeonggyoja did continue into the later Joseon period as a popular means of transport for nobles. A depiction of the royal wedding of King Cheoljong in 1851 portrays a court woman riding on a pyeonggyoja with her face covered, carried on the shoulders of eight porters. A painting of an excursion for enjoying maple leaves by the later-Joseon genre painter Sin Yun-bok features a woman, presumably a gisaeng (female entertaining artist), on an open palanquin. Gama, coming in diverse shapes and purposes, were a practical countermeasure for the limitations on movement created by mountainous terrain. They eventually became a symbol of the status of the passengers inside.

Text by Chung Yeon-sik, Professor in History, Seoul Women’s University

Photos by the National Palace Museum of Korea, National Museum of Korea, and Onyang Folk Museum

양반을 위하여, 가마

로마 시대를 배경으로 한 영화 ‘벤허(Ben-Hur)’에서 주인공은 경기장에서 네 마리 말이 끄는 채리엇(chariot)을 타고 달린다. 중국의 춘추전국시대를 소재로 한 영화에는 말이 끄는 전차가, 미국 서부영화에는 포장마차가 자주 등장한다. 우리나라의 고구려 고분벽화에도 수레가 보이기는 하지만, 산과 골짜기가 많은 지형적 특성상 바퀴 달린 이동수단은 거의 사용되지 않았다. 그래서 말, 나귀를 타거나 가마를 이용했다. 우리나라의 가마를 움직이게 하는 것은 바퀴도, 동물도 아닌 사람이었다.

화려한 가마 속 화려한 신분

가마는 효율적인 이동수단은 아니었다. 박제가가 북학의(北學議) 에서 지적했듯이 한 사람이 움직이는 데 여러 사람이 수고를 해야 하기 때문이다. 그러나 고귀한 사람이 걸어서 이동한다는 것은 과거 신분제 사회에서 격에 맞지 않는 일이었다.만인의 위에 군림했던 조선 시대의 왕은 궁궐 안에서 어지간한 거리라도 지붕이 없는 작은 가마인 여(輿)를 타고 다녔고, 궁궐 밖을 나서면 외부용 가마인 연(輦)을 타거나 말을 탔다. 왕이 타는 연은 물론 가장 화려했다. 네 귀퉁이에 용을 조각한 기둥을 세우고 구슬발과 휘장을 둘렀다. 가마채 끝에는 용머리 장식을 하고 가마 전체에 왕실에서만 사용할 수 있는 붉은 주칠(朱漆)을 하였다. 자동차도 기통 수에 따라 안정성이 달라지듯이 가마는 여러 사람이 멜수록 요동이 덜하였는데 연을 메는 사람은 통상 20여 명에 이르렀다.

관리들 가운데 가장 높은 1품관 정승들은 양교(亮轎)라 불리는 가마를 탔다. 전후좌우로 네 명이 가마채에 끈을 걸어 어깨에 메고 가는데 김홍도의 그림으로 전하는 평생도(平生圖)에는 좌의정이 커다란 부채인 파초선(芭蕉扇)이 늘어진 아래로 가마에 올라 밤길을 가고 있다. 접는 의자를 든 사람과 가마 덮개를 접어 옆구리에 낀 수행원이 앞장서서 길을 비키라고 외치면 그 뒤를 약 20여 명 규모의 수행원이 따른다. 가마에는 머리와 네 발, 꼬리가 온전한 최상품의 표범 가죽을 깔았는데 가마 뒤로 기다란 표범 꼬리가 늘어진 것을 멋으로 여겼다.

말과 바퀴의 힘을 빌려 더욱 특별하게

양교와 견줄 만한 화려한 가마는 쌍교(雙轎)이다. 앞뒤로 길게 뻗은 끌채를 앞뒤 말의 안장에 걸고, 좌우로 짧게 뻗은 끌채는 양쪽에서 가마꾼들이 잡아 균형을 유지하도록 되어 있다. 쌍가마는 판서 2품 이상과 승지(承旨)를 지낸 이만 탈 수 있었다. 그것도 왕과 그 가족이 아니라면 도성 밖에서만 타야 했다. 쌍교는 앞뒤 말이 따로 움직이면 제대로 나아갈 수도 없고 요동치기 때문에 역졸(驛卒)이 옆에 붙어 권마성(勸馬聲)이라고 하는 곡조를 뽑으며 갔다. 그 소리에 말과 마부, 가마꾼들이 발을 맞추었다.

특이한 가마로는 판서급 이상의 관리들이 타고 다니던 초헌(軺軒)이 있다. 일반 가마와는 달리 외바퀴 위에 높다랗게 좌석이 놓여있고, 좌석 앞뒤로 길게 뻗친 끌채 양 끝에 가로 막대를 꿰어 앞뒤에서 밀어서 움직이는 것이다. 초헌은 우리나라에서 세종 때 처음 만든 조선 특유의 탈것으로서, 중국 사신이 신기해하여 짧은 거리를 잠시 태워준 일도 있었다. 관원들의 가마로 가장 자주 사용된 것은 남여(籃輿)로서, 끌채가 앞뒤로 길게 뻗어 있고, 발디딤판과 함께 팔걸이, 등받이가 있다. 본래 남여는 주로 늙은 재상이나 대신들이 타고 다니는 것이었으나 그들의 것만은 아니었다. 왕도 궁궐 안과 궁궐 밖의 가까운 거리를 이동할 때 가끔씩 이용했고, 지방 수령들이 타고 다니기도 했다, 의자 바닥에 발판을 붙이고 끌채를 대어 간단히 만든 것도 있었으며, 대나무로 얽거나 칡끈을 가마채 묶어 메고 다니는 남여도 많았다.

불편할수록 아름답던 여성의 가마

16세기쯤부터는 부녀자들이 벽체와 지붕이 있는 가마인 유옥교자(有屋轎子)를 사용했다. 여자들을 위한 가마인 만큼 외관이 아름답고 섬세했다. 지체 높은 부녀자들이 사용했으며 일반인도 혼례 시에는 탈 수 있었다. 그러나 겉보기에 화려한 이 가마는 사실 타는 사람 입장에서는 그리 편한 것은 아니었다. 사방이 막힌 좁은 가마는 여름이면 너무 더워 몸종이 부채를 부치며 따라다녔고, 멀미가 생기기도 하여 대야를 준비하기도 하였다. 안에는 작은 요강을 넣어 비상시를 대비했다.조선 초기에는 부녀자들도 말이나 나귀, 사방이 트인 가마인 평교자를 탔다. 그러나 유교적 윤리가 강화되면서 부녀자들과 가마꾼의 옷깃 혹은 어깨가 닿기도 하고, 가마꾼들이 부녀자들을 희롱하기도 하면서 문제가 됐다. 그리하여 나라에서 양반 부녀자들은 평교자가 아닌 유옥교자를 타고 낮은 신분의 부녀자들은 말을 타거나 걷도록 권고했다.

하지만 평교자는 값이 싸고 간편하여 조선 말기까지 사용되었다. 1851년에 철종이 혼인할 때의 행렬을 그린 의궤(儀軌)에는 얼굴을 너울로 가리고 8명이 멘 평교자에 올라앉은 상궁의 모습을 확인할 수 있으며, 단풍놀이 다녀오는 광경을 그린 신윤복의 풍속화에서도 기녀로 추측되는 여인이 평교자에 오른 것을 볼 수 있다.

Text by 정연식 (서울여자대학교 사학과 교수)

Photos by 국립고궁박물관, 국립중앙박물관, 온양민속박물관