Feature

The Prodigal Man in Hallyangmu and Talchum

By Kweon Hye-kyung

Dance can express emotions, perform rites, and comment on society. In traditional Korean culture, dance forms that point out the absurdities within social realities by means of satire and humor have long enjoyed wide popularity. Two examples are hallyangmu (the dance of the prodigal man) and talchum (mask dance), both of which express the distress and frustrations that people suffered in the strictly hierarchical society of the Joseon era.

Hallyang, a Man with an Extravagant Lifestyle

During the Joseon Dynasty, the term hallyang, or “prodigal men,” was applied to noblemen who did not hold office and therefore did not work for money, but simply idled away their lives enjoying various entertainments. Today, it also metaphorically denotes those who spend extravagantly and enjoy fully. Hallyang is one of the most popular characters in the traditional performing arts of Korea.

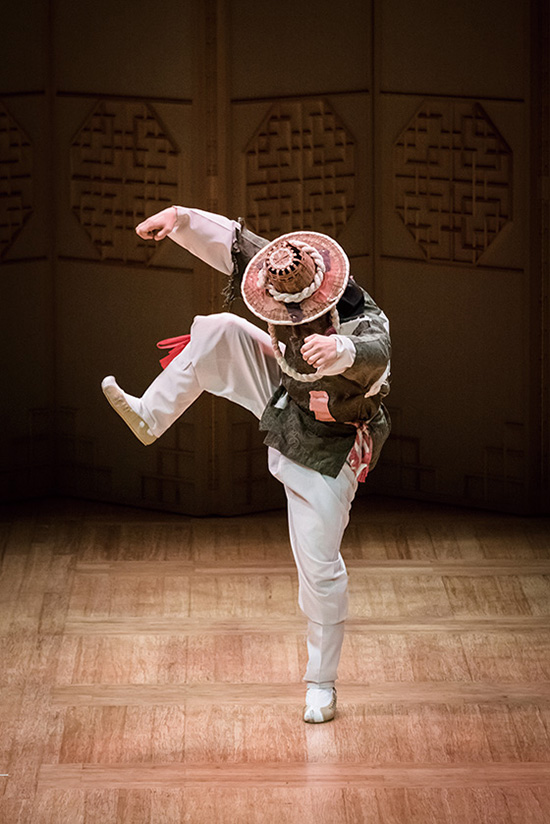

Within the repertoire of traditional Korean dance, hallyangmu, or “dance of the prodigal man,” comes in two variations—one in the form of a theatrical performance presenting a particular storyline and the other as solo piece staged mainly for aesthetic purposes. The former is a drama narrated through choreographic movement the story of a prodigal man and an old Buddhist monk as they contest over the heart of a gisaeng courtesan. In the latter variation of hallyangmu, a male dancer costumed in a robe and hat characteristic of a Joseon literati performs gorgeous and elegant movements suggesting the stylish and playful lifestyle of a hallyang. The dramatic version of hallyangmu merits further attention since its principal storyline of a conflict between a prodigal nobleman and a Buddhist monk can also be found in the plot of talchum, an outdoor performing arts genre featuring masked dancers that gained nationwide popularity in the later Joseon period. This article compares the theatrical hallyangmu and mask dance side by side to spotlight their artistic similarities.

Historical Records on the Dance of the Prodigal Man

Hallyangmu, “dance of the prodigal man,” in its solo dance version. Photo courtesy of

Intangible Heritage Digital Archive.

A historical record of the dance of the prodigal man providing a high level of detail can be found in the 1872 compilation Gyobang gayo (Songs of the Gyobang Office) written by Jeong Hyeon-seok, who served as governor of Jinju from 1867–70. The book features a meticulous description of the songs and dances performed at the district’s Gyobang, an office charged with governing music and dance under the supervision of the local government. It is the only dedicated account of the Gyobang culture of Joseon that has survived to the present. The storyline of the dance of the prodigal man as recounted in the book features a gisaeng courtesan, a prodigal man named Pungnyurang, an old Buddhist monk, and his disciple. The prodigal nobleman approaches a dancing gisaeng, and the two start to court. Entering the stage pulled by his disciple, the old monk approaches the gisaeng and the nobleman and the monk alternate in their attempts to seduce her. Outraged by her indecisive attitude, the nobleman reprimands the gisaeng. When she bursts into tears, he consoles her.

The theatrical version of the prodigal man is a rare example within the repository of traditional Korean dance forms of a silent dramatic performance. The particular variant presented in the book Gyobang gayo has been transmitted as Jinju Hallyangmu (Dance of the Prodigal Man of Jinju), but there are other varieties performed in other parts of Korea, such as in the Seoul/Gyeonggi region and in the Gyeongsang area. These follow different lineages of the practice. Despite slight variations in the composition of the cast, their storylines are fundamentally the same.

Talchum, an Entertainment for the People

Characters for a mask dance: a foolish servant called Imae

Characters for a mask dance: a leper

The term talchum, or “mask dance,” can be exclusively used to refer to masked dances originating in the northwestern province of Hwanghae, such as Bongsan Talchum (Mask Dance of Bongsan,), Gangnyeong Talchum (Mask Dance of Gangnyeong), and Eunnyul Talchum (Mask Dance of Eunnyul). Dance dramas featuring masks were separately called sandae nori (playing on an outdoor stage) in the Seoul/Gyeonggi area, and in the Gyeongsang region as deul noreum (playing in a field) and ogwangdae (five clowns). To fully capture the distinctive characteristics of this type of dance, the term talchum has since been established as a generic description of all regional dance dramas performed wearing masks. Actively transmitted throughout the Korean Peninsula, the broader mask dance genre features a diverse range of characters: a lazy nobleman overflowing with vanity and his servant Malttugi, who critiques his master using satire; an apostate Buddhist monk who represents corruption within the Buddhist community; a young gisaeng and a grandmother who is pitted against her; and a drunken man called Chwibari who competes with the Buddhist monk over the young courtesan. These characters manifesting social realities of the late Joseon period entertain the audience through stories of their conflicts and reconciliations.

Chwibari is one of the major characters in the mask dance cast and takes on the role of the prodigal man (hallyang). His mask is typified by a reddish color alluding to his intoxication and by the several wrinkles on his forehead from which a long strand of hair hangs loose. A willow branch in his hand and a bell wrapped around his knee serve as his symbolic objects. As with the nobleman in the dance of the prodigal man, Chwibari disputes with an old Buddhist monk to win over a gisaeng. First competing through a dance contest, Chwibari loses, but he beats the monk away with violence. Chwibari then uses money to curry favor with the gisaeng. Taking a step farther than his counterpart in the dance of the prodigal man, he seduces the gisaeng and fathers a child with her.

Characters for a mask dance: a grandmother

Similar but Unique

As described above, the two forms of traditional dance—the theatrical version of hallyangmu and the mask dance, or talchum—feature similarities in their plots and characters. The differences mainly stem from the use of dialog and masks in the performance. While the dance of the prodigal man is a typical dance drama conducted without dialog, mask dance features words and songs and are consequently better suited to conveying a sense of satire and humor. Compared to a dance drama, the masks in a mask dance serve to visually exaggerate the personalities of the characters. A mask offers a performer the liberty to overemphasize the movements of the dance and clearly bring across the persona being portrayed. A good example is Grandmother, a common mask dance character known for a pronounced swaying in her walk. Mask dances were performed and developed by residents within the very arenas in which their daily lives took place while the dance of the prodigal man was reserved for professionals. While the dance of the prodigal man was of a more official nature and conducted by entertainers hired by local governments, mask dance provided a popular outdoor event that ultimately united performers and spectators within an exhilarating atmosphere. The dance of the prodigal man enriches the repertoire of traditional Korean dance through its unique form as a dramatic performance. Serving as popular entertainment, there has been a mask dance revival since the 1970s when university students adopted it as one of the most significant cultural features of the nation. The two dance forms featuring a prodigal man are both indispensable assets in the traditions of Korean dance.

Text by Kweon Hye-kyung, National Gugak Center

Photos by the National Gugak Center

스토리가 있는 전통춤 한량무와 탈춤

춤을 춘다는 것은 기쁨과 슬픔의 감정, 의식과 절차의 수행, 사회와 현실의 풍자를 사람의 몸으로 그려낸다는 것이다. 특히 우리 전통 문화에는 사회 현상을 해학적 이야기로 표현하는 춤이 대중과 함께 오랜 시간을 살아오고 있다. 조선시대의 신분 구조와 대중의 삶을 고스란히 담아낸 한량무와 탈춤이 그렇다.

극형식을 갖춘 독특한 전승춤, 한량무

한국 전통춤에는 두 가지 유형의 한량무가 있다. 하나는 스토리를 가진 무용극 형식의 춤이고, 하나는 남성 독무이다. ‘한량’이란 조선시대 일정한 직책이 없이 놀고먹던 말단 양반 계층을 이르는 말이었으나 요즘은 돈 잘 쓰고 잘 노는 사람을 비유적으로 이르는 말로 쓰이기도 한다. 이와 같이 ‘노는 남자’ 한량의 캐릭터는 한국의 전통 예술 곳곳에 등장한다.

두 가지 유형의 한량무 중 전자의 한량무는 한량과 노승이 기생을 두고 대결을 벌이는 스토리를 몸짓과 춤으로 풀어가는 일종의 무용극이다. 후자의 남성 독무 한량무는 도포에 갓을 쓰고 풍류를 즐기는 우아하고 멋스러운 남성의 풍모를 보여주는 춤으로, 현재 전통춤의 중요한 레퍼토리로 자리 잡고 있다. 이 가운데 극형식 한량무는 조선 후기 전국적으로 성행한 탈춤의 노장 과장과 유사한 구조를 가지고 있어서 이 글에서는 탈춤과 극형식의 한량무를 함께 소개해 보고자 한다.

한량무에 관한 기록

한량무에 관한 비교적 상세한 기록은 1872년 정현석이 펴낸 책 『교방가요』에 나온다. 정현석은 1867년부터 1870년 경상남도 진주의 관리를 지냈다. 『교방가요』는 진주 교방(관아에 부속된 춤과 음악을 관장하던 기관)에서 연행하는 춤과 음악에 관한 상세한 기록물로 교방 문화를 기록하기 위한 목적으로 쓴 책으로는 유일하게 전해지는 것이다. 이 책 속 한량무에는 기생, 풍류랑(한량), 노승, 상좌가 등장하는데 스토리를 요약하면 다음과 같다. 젊은 기생이 춤을 추고 있는데 한량이 등장하여 서로 희롱한다. 이때 노승이 상좌에게 이끌려 기생에게 다가간다. 한량과 노승이 번갈아 기생에게 신발을 신겨주며 기생을 유혹한다. 한량은 노하여 기생을 꾸짖고 기생이 울자 달랜다는 내용이다.

한량무는 대사 없이 춤과 몸짓의 연기로 이루어지는 일종의 무용극이라는 점에서 주목할 만하다. 한국 전통춤 가운데 스토리를 가진 무용극은 흔하지 않기 때문이다. 『교방가요』에 소개된 한량무는 현재 진주한량무라는 이름으로 전승되고 있다. 그 외에도 서울․경기 지역의 이동안류 한량무, 한성준 계열의 한량무, 경상도 양산의 김덕명류 한량무 등이 전해지며, 이 춤들은 등장인물에 약간의 차이는 있으나 기본 스토리 구조는 모두 유사하다. 그런데 기생을 사이에 두고 한량과 노승이 대결하는 이러한 구도는 탈춤에도 등장한다.

조선시대 민중의 놀이판, 탈춤

탈춤은 탈을 쓰고 춤을 추면서 공연하는 연극이다. 원래 탈춤이란 용어는 봉산탈춤(국가지정무형문화재 제17호), 강령탈춤(국가지정무형문화재 제34호), 은율탈춤(국가지정무형문화재 제61호)과 같이 황해도 지역의 탈춤을 부르는 용어였다. 탈을 쓰고 춤추는 이러한 형태의 공연을 서울․경기에서는 산대놀이라 하였고, 경상도 지역에서는 들놀음, 오광대라고 한다. 그런데 ‘탈춤’이라는 용어가 가장 의미를 전달하기에 적절해서 이런 유형의 공연물들을 통칭하는 용어로 일반화되었다. 황해도 봉산에서부터 경상도 동래에 이르기까지 한반도 전역에서 추어지며 현재까지 전승되고 있는 탈춤에는 다양한 캐릭터들이 등장한다. 허영과 거드름을 피우는 양반, 그런 양반을 비꼬는 말뚝이, 불교의 타락상을 풍자한 파계승, 젊은 기생과 대결하는 할미, 기생을 사이에 두고 노승과 갈등하는 취발이 등 당시 사회상을 반영하는 전형적인 인물들이 대결하고 화해하며 극적 재미를 이끌어간다.

천하의 한량, 취발이

취발이는 탈춤에 등장하는 한량이다. 취발이의 가면은 술에 취한 듯 붉은색을 띄며 이마에 여러 개의 주름이 잡혀있고 길게 늘어진 머리카락을 가지고 있다. 손에는 버드나무 가지를 들고 방울을 달고 있는 것도 특징이다. 취발이는 앞에서 살펴본 한량무와 같이 기생을 사이에 두고 노승과 대결을 펼친다. 춤으로 대결을 해보지만 이기지 못하여 결국 노승을 때려서 내쫒는다. 취발이는 돈으로 기생의 환심을 사고, 한량무의 풍류랑보다 한발 더 나가 기생을 희롱하여 아이를 낳는다. 아이에게 천자문을 가르치자 아이가 기생방 출입을 위해 언문을 가르쳐달라고 하는 등 해학적인 내용을 담고 있다.

이와 같이 한량무와 탈춤은 한량(풍류랑)-취발이, 승려(중)-노장, 색시-소무, 상좌-목중으로 동일한 인물들이 유사한 스토리 구조를 이루고 있다. 다만, 한량무는 탈을 쓰지 않으며 대사가 전혀 없는 무언극으로 진행된다는 점이 다르다. 탈춤의 탈은 인물의 전형적인 성격을 과장된 방식으로 시각화한다. 연희자가 탈을 쓰게 되면 몸짓과 춤동작도 다소 과장되는 경향이 있다. 사실적이고 섬세한 표현보다는 캐릭터의 특징을 단순화하여 과장된 몸짓으로 춤을 춘다. 거의 모든 탈춤에 등장하는 할미가 엉덩이를 좌우로 실룩거리며 걷는 춤사위를 대표적인 예로 볼 수 있다. 또한 탈춤은 대사와 노래가 있기 때문에 내용의 전달력이 좋으며 해학적인 내용과 우스꽝스러운 형상과 몸짓이 주는 재미가 있다. 그리고 무엇보다 탈춤은 지역을 기반으로 한 민속 현장에서 연행되며 전승을 이어왔다. 한량무는 연행주체가 탈춤보다 전문가 집단이었으나 실내 극장 무대화 레퍼토리로 성장하기에는 볼거리가 약했다고 생각된다. 최근에는 남성 독무의 일인무로서 많이 공연되고 있다. 극형식 한량무와 독무 한량무의 직접적인 관련성은 아직 명확하게 밝혀진 바가 없다.

한량무와 탈춤 전승의 의의

오늘날 한량무의 가치는 그 양식적 독특함에서 찾을 수 있다. 탈춤이 공연하는 사람과 구경하는 사람이 하나로 어우러지는 광장의 예술이었다면, 한량무는 관기들에 의해 보다 공적인 공간에서 추어진 교방의 춤이었다. 탈춤은 19세기 사회상을 반영하며 전국에서 성행한 민중의 놀이판이었으며, 시대를 넘어 1970년대 말부터 대학가를 중심으로 민족문화에 대한 관심이 고조되면서 탈춤부흥운동으로 이어지기도 하였다.

이와 같이 한량무와 탈춤은 한국 공연예술에 없어서는 안될 소중한 무형 자산이다.

글 권혜경 국립국악원 학예연구사

사진 국립국악원