Feature

The Oldest but the Most Effective and Cutting-Edged Heritage

By Yongwook Yoo

What characteristics make the humankind distinguish itself from other animal species? One might suggest bipedalism, language, social interactions, and etc., but we need materialistic evidence in order to be archaeologically implicative. Then the oldest man-made artifact can be the first material evidence to indicate that humankind can be separated from other species. The Paleolithic implements, artifacts made of stones during the Old Stone Age from about three million and a half (3.5Ma) to ten thousand years ago (10Ka), can be considered to be such evidence.

Unlike other periods of human history, the Old Stone Age, aka the Paleolithic period, is a time-span of bipedal primates—the hominins—who were genetically and behaviorally more like wild animals than modern humans. Since they lacked intelligence and physical capacity of modern humans, the early hominins were rather prey to other carnivores than themselves being the predators. The stone tool-making was an evolutionary solution that hominins developed as their adaptive strategies beyond their physical limitations. With stone tool-making skills, they gradually came to exert their own enhanced survival capacity, transformed themselves from herbivore to carnivore, enlarged their brain size by intaking animal protein, and finally became the primatus omnima far above other species.

While making stone tools and becoming meat-eating carnivores, early hominins evolved into genus Homo—such as Homo habilis who used simple stone tools—and their gradual incessant speciation led to us, anatomically and behaviorally modern humans, the Homo sapiens. In that course of evolution, hominins produced and left diverse Paleolithic artifacts and expanded their living territory as they left Africa from where they originally emerged. They traversed the Middle East and the Caucasus to finally reach every corner of Europe and Asia. In this sense, the hominin group who finally arrived on the Korean Peninsula, the far eastern cul-de-sac of Eurasia, might be one of the most daring and tenacious trailblazers because few would break through such natural obstacles as the Himalayan Mountains and the Gobi Desert.

The Oldest Paleolithic implements: simple choppers with sharp-edged flakes and handaxes

It is not clear which hominin species might have arrived on the Korean Peninsula but Homo erectus is arguably considered the first Korean hominin since the fossils of the same species were discovered as the Peking Man in China and the Java Man in Indonesia. The erectus group of Asia is generally dated about 0.5Ma at its youngest. Even though this population is now entirely extinct, the erectus inhabited widely across the Asian continent including the Korean Peninsula and made various Paleolithic artifacts. With such solid stone tools, they could transform raw materials such as wood, bamboo, and bone into reliable handy implements. The stone tools we witness now might be some basic or “meta” tools that were ready-made for producing other implements of daily necessity. The early Paleolithic implements, therefore, were not meticulously designed and could serve to simply modify other materials. This type of implements includes a chopper and chopping-tools made of casually fractured pebble stones, as well as sharp-edged flakes and debris detached from them. These implements are seemingly no more than naturally broken stone fragments. As such, the oldest stone tools might have been produced by directly using previously broken angular and edged rocks as well as intact pebbles.

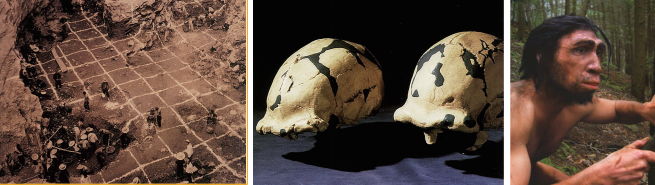

Left The Zhoukoudian site of China

Center Is famous for the first discovery of hominin fossils in East Asia, the skulls of the Peking man

Right They are believed to have inhabited in the forest environment using simple tools for making other perishable implements

Left The Oldowan tools discovered in Ethiopia dated about 2.4MA

Right Quite identically simple choppers and flakes are also discovered in Korea (right) but their age is by far younger than the African Oldowan tools.

The Old Stone Age is normally divided into three sub-periods: Lower (Early), Middle, and Upper (Late) Paleolithic. Lower Paleolithic (3.5-0.3Ma) is defined by the simplest technology represented by choppers and flakes mentioned above. This technology is called “Oldowan industry” and is the first tool-making phase in human history. Such a rudimentary technology is also observed on the Korean Peninsula. However, technology dated as old as several million years (Ma) ago has not been discovered yet. The reason for this is that it took quite a long-time span for hominins out of Africa to finally arrive on the Korean Peninsula.

Around about 1.8 Ma a new advanced technology emerged in Africa; hominins began to manufacture a rather standardized stone tool—the handaxe or biface. The handaxe, which is a bifacially shaped symmetrical tool with a pointed tip, is evidence that stone tools are now designed for efficacy. Pointed stone tools already existed in the previous Oldowan industry but a handaxe, a single piece equipped with a tip and double symmetrical side edges, is the result of stylistic and functional epitomization; this clearly indicates that Homo erectus attained technological advancement enabled by their intellectual development which entails the practical making/using of desired stone tools. The technology of handaxe in Africa and Europe is referred to as the “Acheulian industry.” Those two industries—Oldowan and Acheulian—are major technological traditions of the Lower Paleolithic Old World.

The Acheulian is predominantly distributed in the western part of Eurasia, especially to the west of the Indian subcontinent. The handaxe is, although not quite as many as in Europe and Africa, also discovered in East Asia; one of those well-recognized East Asian handaxe localities is the Imjin-Hantan River Area (IHRA) of the Korean Peninsula and its most well-known example is the Jeongokri site in Yeoncheon County of Gyeonggi Province.

Handaxe and other Paleolithic artifacts of the Imjin- Hantan River Area: their unique time range and technological characteristics

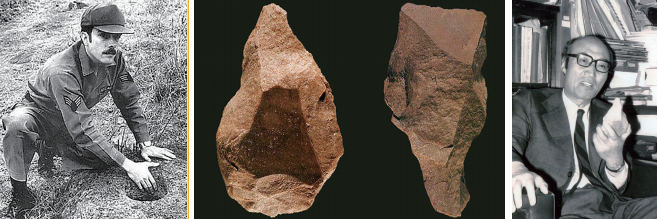

Until 1978, Jeongokri was a mundane military camp town adjacent to the De-militarized Zone. Greg L. Bowen (1950-2009), a USFK airman who majored in archaeology during his college days, came across several Acheulian-like handaxes while dating his girlfriend at a Jeongokri riverside resort. At that time, Bowen had been educated that East Asia was devoid of genuine Acheulian handaxe according to an established archaeological theory championed by Hallam L. Movius (1907-1987) of Harvard University. Bowen was quite excited by his discovery and wrote to François Bordes (1919-1981) of Université de Bordeaux I, a prestigious French Paleolithic archaeologist. Also astonished, Prof. Bordes immediately replied that one of his old students had come from Seoul National University (SNU) of Korea and urged Bowen to consult Dept. of Archaeology at SNU. Bowen, therefore, handed his discoveries and field notes to Prof. Won-yong Kim (1922-1993); this led the SNU Museum to take the initiative to officially excavate the Jeongokri site. Starting with the Jeongokri site, several other Acheulian-like Paleolithic localities—Gawolri, Juwolri, Geumpari, Namgyeri, and Wondangri, etc.—have been successively identified and excavated in the IHRA since the 1980s.

Left Bowen who was a USAF sergeant deployed at Camp Casey, Dongducheon

Center Discovered several Acheulian-like artifacts Jeongokri in 1978

Right And reported them to the late Won-yong Kim, a Korean professor of archaeology in SNU then. This discovery kindled a number of excavation sessions and archaeological publications for about 40 years until now.

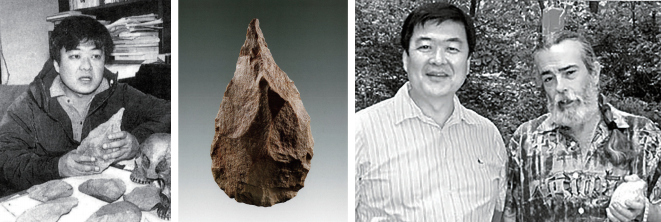

The Jeongokri handaxe, a critical counterevidence to Movius’ old theory, was believed to be of Lower Paleolithic since it is similar to the classic Acheulian handaxes from Africa and Europe. Below the Jeongokri deposit where the handaxe is discovered lies a basalt bedrock formed by the volcanic eruption from North Korea. The absolute age of this basalt bedrock is estimated to be 0.5-0.3Ma by potassium-argon (K-Ar) dating method, and the age of Jeongokri handaxe has been calculated to be of Lower Paleolithic contemporaneous with the Acheulian industry. This age was reconsidered and refuted by Seonbok Yi (1957-) who succeeded Won-yong Kim and continued the research of Jeongokri at SNU. He observed that the handaxes of Jeongokri were actually distributed far above— quite younger than—the basalt bedrock and even discovered just below the horizon of the Aira-Tanzawa (AT) volcanic ashes which have a solid date of about 30,000 years ago (30Ka). As of now, it is clear that the age of the IHRA handaxes including those from Jeongokri, falls between 70 and 30Ka based on the diverse chronometric dates and geological evidence.

Left Seonbok Yi who is currently teaching archaeology and conducting archaeological research in SNU

Center Discovered several IHRA handaxes such as the one from the Gawolri site and established a solid dating framework of the IHRA handaxes.

Right He re-united with Bowen (right) in 2005 at Jeongokri,

36 years after the first discovery of the handaxe.

Such a relatively young IHRA handaxe comes from the Middle Paleolithic rather than the Lower. The Middle Paleolithic industries of Africa and Europe (about 0.3Ma to 40Ka) rarely host Acheulian technological elements except for a few late degenerated forms. During the 2 Middle Paleolithic period, especially in Europe and Middle East, the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), a unique hominin group well-adjusted to the cold and dry Last Glacial period (about 115,000 to 11,700 years ago), produced the “Mousterian Industry” which is characterized by a higher percentage of small flake-based retouched tools. However, East Asia, including Korea, lacks any fossil evidence of Neanderthals and likewise, Middle Paleolithic artifacts similar to Mousterian implements are not common. Recently, however, the fossils and DNAs of the Denisovan, the 3rd hominin population, who cohabited with both Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) during the last phase of the glacial age, are found in the Denisova Cave of Siberia, Russia. Since its holotype fossil is yet to be designated, the Denisovan species name is not denominated either. It is postulated that the Denisovan group occupied East Asia, contemporaneously with the Neanderthals in Europe and West Asia; they even possibly cohabited with local Homo erectus population or replaced them to eventually become the sole survivor group producing the late handaxes during the Middle Paleolithic of the Korean Peninsula. This hypothesis will await more clear and detailed evidence of paleoanthropology and Paleolithic archaeology in the future.

The Significance of Korean Paleolithic Implements: the oldest and the most reliable living commodities of ancient Koreans

From about 40Ka, the Upper Paleolithic industry emerged and became prevalent across the Old World including the Korean Peninsula. The Upper Paleolithic is generally considered as the technology of the new hominin group, the Homo sapiens. It is marked by the regular production and use of a blade; a new type of stone implements with long and laminar shape made by a specialized striking technique. Homo sapiens, who originated about 0.3Ma in Africa, migrated and pervaded into entire Eurasia by 40Ka. In that course of global expansion and occupation, they replaced indigenous hominin populations like the Neanderthals and Denisovans; or they interbred with them to trigger genetic mutations. The current racial distribution of Africa, Europe, and Asia might be the final result of these multiple and entangled genetic mutations among diverse hominin groups on a global scale.

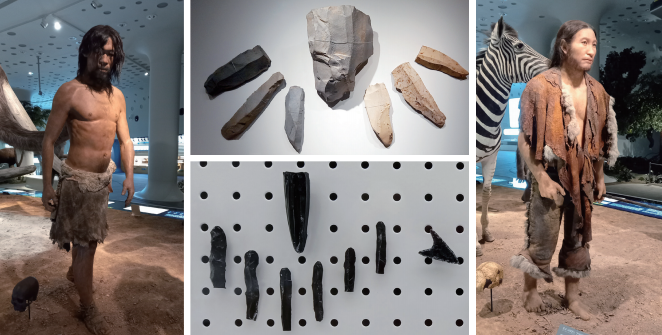

Left Stemmed point a unique stone tool type characterized by vivid stem with pointed tip. It is easy to imagine that this tool was specially used for hunting weapons during the extremely cold LGM

Right Correspondingly, a majority of archaeological discovery is composed of broken fragments resulting

from damages of heavy usage .

LeftA few fossils of the Korean sapiens group have been discovered in North Korea. A reconstruction of Korean sapiens is based on several crania and bones discovered at the Yonggok Cave near Pyongyang City.

Center top Korean sapiens were skilled tool-makers specialized in blade production out of prismatic cores

Center bottom Associated with microlith, a set of very tiny blades and cores made of highly valued rock materials like obsidian

Right Another sapiens fossil was also discovered at Mandalri

The Upper Paleolithic tools made by Homo sapiens are mainly composed of relatively small and intensively modified implements made of diverse rock types. These tools are closely related with hunting the animals and hiding works since plant resources were scarce due to the extremely cold and dry period of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM; about 30- 16Ka) which was the most harsh and barren climatic event before the beginning of the current climate. In order to compete with other hominin groups and animals under the stressful environment, the Korean sapens group devised more effective and technologically advanced toolkits. They changed their raw materials from crude quartz and quartzite to more refined microcrystalline rocks. They even travelled more than hundreds of kilometers to acquire better rock materials; for example, the sapiens groups in the midwestern part of the Korean Peninsula reached the Baekdu Mountain of the far north to quarry obsidian rock nodules, a fine-grained volcanic glass characterized by its good elasticity for making delicate and sharp implements. In addition, they utilized such new rock materials as tuff and rhyolite that have never been used before. For the purpose of economizing these precious rocks, the unit size of stone tools became smaller and these tools were sometimes designed to make “stemmed points” which were hafted on handles in order to maximize the available length of the final gadgets. The Korean sapiens even produced “composite tools” by combining miniscule stone bladelets with bone or antler frames.

Equipped with better surviving strategies, the Korean sapiens group underwent and overcame the cold glacial period by achieving the technological innovations explained above. The Homo sapiens fossils from Mandalri and Yonggok Cave of Pyongyang area are good examples of those Korean survivors. Afterwards, the global climate has become warmer and normal like today. The Paleolithic period ends and the new neolithic begins from about 10Ka. With the rise of the global temperature, the sea level also rose to form the current coastal lines of the Korean Peninsula, separated from continental China and the Japanese Archipelago. With the end of the Paleolithic period, survivors on the Korean Peninsula began to exploit marine resources in the newly demarcated land, witnessed the emergence of agriculture, formed their very first own civilization, and finally welcomed the historical era.

The longest period within the career of the people on the Korean Peninsula is the Paleolithic. Since about 0.5Ma, Korean hominins made their livings solely depending on stone implements. In this regard, we can argue that residents on the Korean Peninsula attained their own life styles and technological traits through Paleolithic implements far before the formation of the traditional culture on the Peninsula. The uniqueness of Korean proto-culture before the emergence of Korean folks can be seen by these Paleolithic properties. In particular, the independently produced non-Acheulian handaxe and the stemmed point unprecedented elsewhere in Asia demonstrate the ingenuity of the Korean Paleolithic technology. This Korean Paleolithic ingenuity—innovation and uniqueness— has been bequeathed and inherited from generation to generation via genes of the Korean people; and this is the epitome of our very remote past which is yet to be heralded.