Feature

Traditional Korean Gardens Unite Nature and Humanity

By Shin Hyun-sil

Many Koreans are using the term meong these days. Being in meong means falling into a trance-like state with the eyes fixed on a natural element like fire or water. Staring at elements of nature for an extended time is a good way to ease worries and bring peace back to the mind. It is also a perfect recipe for sparking imagination and fueling creativity. Although meong is a new addition to the Korean vocabulary, contemporary Koreans are not the first to practice clearing their minds by gazing at nature. It was also a popular practice among scholars during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). They often performed it in a garden that had been designed to blend with nature.

Gwanghallu Pavilion surrounded by nature

While architecture merged with horticulture holds the central position in traditional Western gardens, the native gardens of East Asia focus on the relations between humanity and nature while creating a mental space for deep contemplation. Gardening in Korea shares affinities with other countries in the cultural sphere, but also eventually developed distinctive characteristics setting it apart from the traditions in China and Japan.

Garden construction in China was strongly influenced by Daoist ideals. Gardens were built as an actual representation of a natural scene, typically the utopian landscape inhabited by the Daoist immortals. One key to expressing this mystical space were taihu stones and other rocks in imaginative shapes, collectively known as scholar’s rocks. Found around Lake Tai in Suzhou, Taihu stones are characterized by their numerous pores and holes created over millennia of submersion in water. These porous stones with their convoluted geometry were placed in gardens to imbue them with a mystical atmosphere.

Gardens were also considered representations of nature in Japan. However, these landscapes were highly miniaturized and expressed through more abstract symbols. Natural scenes, Daoist utopias, and Buddhist paradises can all be expressed in a Japanese garden within a small frame rich in abstract symbolism. While maintaining distinctive characteristics, traditional gardens in China and Japan are similar in many ways as the former heavily influenced the latter.

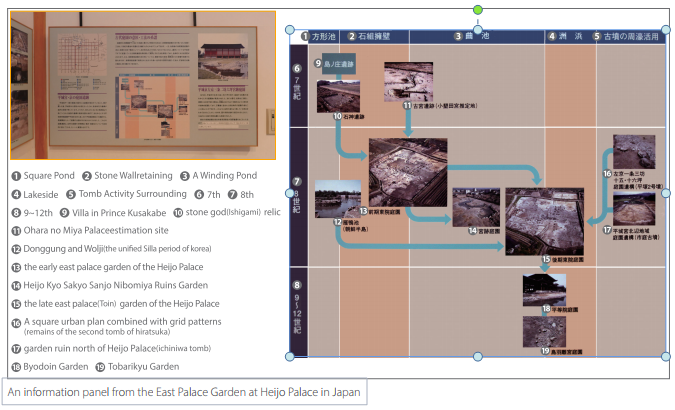

The Korean Peninsula served as a bridge between China and Japan: gardening ideas and practices imported to Korea from China were then disseminated in Japan. For example, Shanglin Park, an imperial garden in China dating to the Han Dynasty, influenced the garden of the prince’s palace in the Silla Kingdom, one of the three ancient kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula. Silla’s princely garden in turn impacted Japan’s Heijo Palace. Although formed within the same network of cultural exchanges taking place across East Asia, gardens in Korea were not as prominent as those in China and Japan in terms of scale or symbolism. They are, however, notable for their expression of an aesthetic of simplicity, highlighting the virtue of moderation, and inviting in nature in a pure state.

Imported Chinese gardening culture predominated in Korea until the Joseon era, but local ideas and practices developed during the second half of the dynasty based on Confucian ideology. Confucianism was born in China, where this age-old basis of traditional Chinese life ended up being suppressed as an obstacle to communist reforms with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in the mid-20th century. After Korea’s absorption of Confucian concepts from China, they continued to be practiced and further developed. By the second half of the Joseon era, Confucian philosophy was actually thriving to a greater extent in Korea than in its native China. It served as inspiration for Korea’s garden-construction tradition.

Soswaewon Garden

In the conception of gardens in Korea, people were regarded as part of a larger natural cycle. Gardens were not just built as a component of residential complexes. A natural area itself could be turned into a form of garden with some minimal human intervention: A pavilion built amid beautiful scenery or a bounded area of nature used as a secondary home was also considered a kind of gardening in Korea. Decoration was restricted and simplicity was pursued, ensuring that the garden could blend with the surrounding natural environment and eventually become one with it. A harmony was struck between the various parts of a garden: Trees were kept small so as not to overwhelm the architectural structures; scholar’s rocks did not serve as a center of attention but were set in balance with other elements; and ponds were made along the axis of buildings and in a square form. Within this space, Joseon scholars could spend time cultivating themselves as Confucian gentlemen.

A “flower stairs” garden at Gyotaejeon Hall, Gyeongbokgung Palace

Upholding the important Confucian virtues of filial piety and loyalty, Korean gardens manifested the hierarchy between those taking different roles in society. Gardens for aristocrats were more modest than those for kings, and a garden planted by an ancestor was maintained intact over the generations with few alterations. This spirit of filial piety is shown clearly in Soswaewon, one of the definitive traditional gardens in South Korea. This garden house was built in the 16th century by a Joseon scholar named Yang San-bo. It has been maintained ever since by his descendants with little change to its form or scale.

A terraced garden at Nakseonjae House, Changdeokgung Palace

Korean gardens typically respected the given topography. One technique derived from this spirit of partnership with nature was “flower stairs,” or hwagye. When building a house, surrounding slopes were terraced to make “flower stairs” that served both as retaining walls and gardens. Some of the best examples of the hwagye terraced gardens from the Joseon era include those at Gyotaejeon Hall at Gyeongbokgung Palace and Daejojeon Hall, Juhapnu Pavilion, and Nakseonjae House at Changdeokgung Palace. The Soswaewon garden also has such “flower stairs.”

As humans were considered a part of nature, beautiful landscapes did not need to be laboriously reproduced within a compound as a personal possession: They could be “borrowed” as needed for appreciation. Korean scholars appreciated the scenery outside their houses through architectural frames made by people, like windows and doors. This was known as “borrowed scenery.” Byeongsan Seowon Confucian Academy is worth a visit in this regard. The pavilion called Mandaeru positioned in the front section of this Confucian institution perfectly draws the outside scenery into the field of vision of the people inside.

Traditional Korean gardens are still spaces where contemporary Koreans can enjoy a profound communication with nature just as their ancestors did. They are also areas for learning lessons about deep respect for nature and for other people. The traditional Korean virtues manifested in Joseon gardens will be of help to the generations of today as we navigate the future.

Mandaeru Pavilion seen through the frame of the building behind it at Byeongsan Seowon Confucian Academy