Feature

Household Duties of Men in the Joseon Era

By Jeong Chang-kwon

Men during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) played an active role in the management of household affairs. A typical household of the yangban ruling class would have 50 to 100 members, including servants. A wide range of matters needed to be taken care of within each household, from securing food and producing daily necessities to ensuring children’s education, controlling disease, and fulfilling religious duties. During the Joseon period, each household functioned as a self-sufficient society.

History of Mixed Gender Roles

The Confucian society of the Joseon era cherished the notion that stability in the household would provide a foundation for peace in the nation. The top priority was placed on the domestic sphere, and social activities were carried out to support it.

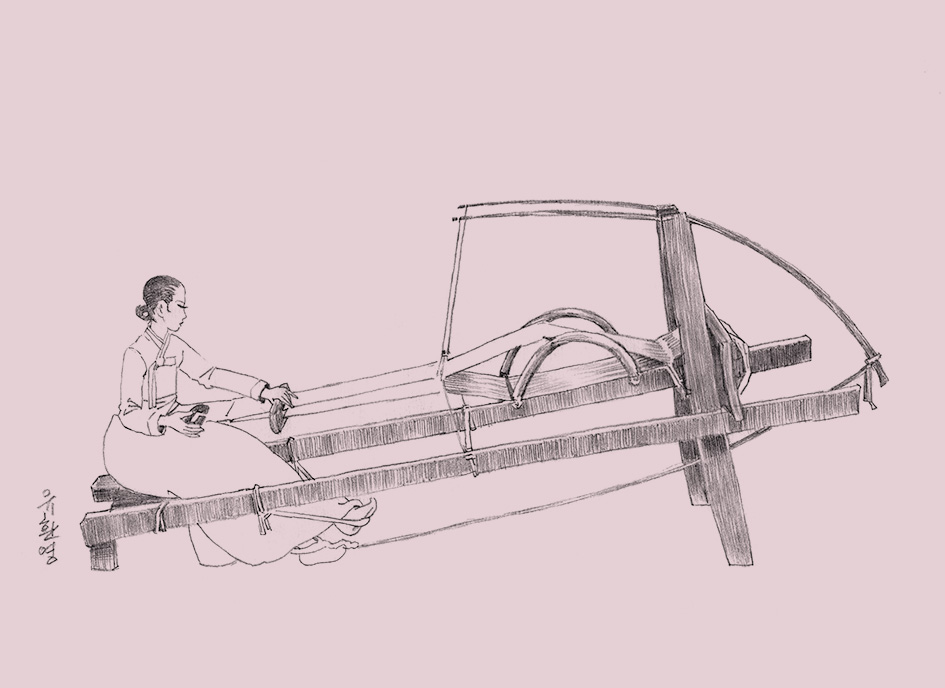

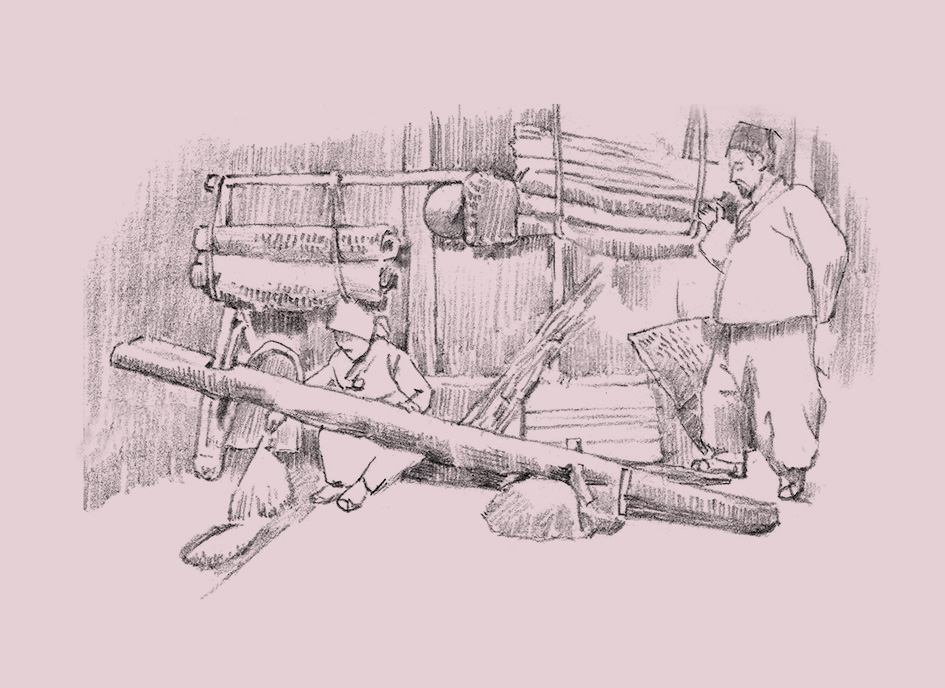

Household responsibilities were divided into two categories of duties, namely “inside” and “outside” affairs. Inside affairs like meal preparation and weaving cloth fell under the responsibility of female members, while men carried out outside affairs such as earning a living, raising the value of the household property, and managing servants. Male members also actively participated in affairs taking place within the boundaries of a household through their contribution to garden management and children’s education.

Women had to dedicate all their time and effort to inside affairs since their time-consuming work was critical to the life of a household. For example weaving was not just necessary to provide clothes for family members: Rolls of cloth were also used as a currency and paid in taxes. An inside activity as simple as cooking rice could be a lengthy process involving multiple tasks from milling the rice to building the fire. On top of all this, there was a wide range of chores associated with pregnancy and childbirth. Women had no spare time to spend on outside affairs.

Although there were household duties that were normally associated with men and women, gender roles could be quite flexible during the Joseon era. The 16th-century poet Song Deok-bong provides a useful example. While her husband was away serving in the government or living in exile, she oversaw both the inside and outside affairs. In contrast, the 18th century scholar Park Ji-won took over all the inside responsibilities after the death of his wife, including educating their children and taking care of meals.

Secret but Still Active

In later period of the Joseon Dynasty family lineage emerged as the key determiner for being granted an official post in the government. Yangban noblemen without a previously successful lineage had little chance to enter the officialdom so an increasing number of noblemen were unable to make inroads into society. Without a need to serve in the government, they found themselves with considerable free time to devote to scholarship. Of course, many of them simply idled away their time with little concern for their households. They were unable to work if they wished to maintain the benefits of their yangban status since working for the purpose of making a living meant they would have to shoulder the tax obligations of a commoner.

In addition, ideas from Neo-Confucianism were taking deep root in Joseon society at the time. The separation of men and women accordingly strengthened, and social views on men’s participation in household affairs started to change. Performing domestic duties came to be considered increasingly unpleasant, and even embarrassing, for men. As they began to turn their backs on household affairs, women had to fill in the gap. Female members of a household were forced to take charge of the outside portion of household management as well. They added to their already long list of inside duties the additional responsibility of making a living on behalf of their household.

Of course, men were not completely free from the responsibility of household affairs during the later period of the Joseon era. It would be impossible to support a group of 50 to 100 people without some contribution from its male members. It was just that their participation in domestic efforts was not something they took pride in and needed to be kept hidden from others. This was similar to a situation that women faced at the time since Joseon society did not welcome creative activities by females and they therefore had to hide their literary efforts or publish them anonymously.

Modern-day Patriarchal Gender Divisions

The natural question arises as to when Korean society gained its current patriarchal perceptions on gender roles and drawing a clear dividing line between men and women. Today’s strictly patriarchal gender roles took form in Korean society only relatively recently, mainly during the Japanese colonial era and the subsequent industrialization period.

Under the Japanese colonial rule that lasted from 1910 to 1945, greater emphasis was placed on activities outside the domestic domain. Society was increasingly perceived as consisting of two distinct spheres—the private and the public—and households were immediately set in the private category. The flexibility in gender roles that had been observed to varying degrees during the Joseon Dynasty vanished, and strictly binary ideas about what men and women should do within society set in. This new order for gender roles demanded that men go out and fully dedicate themselves to economic activities while women remain at home taking charge of all the domestic duties, including child-rearing responsibilities.

The industrialization processes taking place starting the 1970s cemented the separation between the private and public domains, furthering the division of labor between men and women. Women during this period were increasingly required to become the sole provider of love and affection within a household. Against this background emerged a growing perception defining men as producers and women as consumers, and the domestic sphere was undervalued as simply a place for consuming and resting, not an area related to productive activities.

Women’s social participation is accepted as a norm in contemporary society. It is essential to ensure that both men and women can equally enjoy the freedom to participate in the domestic and public spheres in Korean society. Equally as important as women’s involvement in socioeconomic activities is men’s responsibility to strike a balance between their work and family responsibilities. They need look no further than their Joseon forefathers to learn about how to fulfill their share of domestic responsibilities while doing their part in serving the state.

Text by Jeong Chang-kwon, Culture and Creation Department of Korea University

Illustration by Yoo Hwan-young

조선의 살림하는 남자들

조선시대 남성들은 집안 살림에 적극적으로 참여했다. 우선 조선시대 집안의 규모는 오늘날 50~100명의 직원을 둔 중소기업체 정도로 컸다. 의식주에 필요한 생활필수품도 집안에서 생산했고, 자녀교육이나 질병치료, 종교활동도 집안에서 이루어졌다. 조선시대 집안은 오늘날의 작은 사회와 같은 곳이었다.

남녀 공존의 역사

조선시대는 ‘수신제가치국평천하(修身齊家治國平天下)’라고 하여 집안을 안정시킨 후에 나라를 다스리라는 말을 중히 여겼다. 사회보다는 집안이 우선이었고, 모든 바깥 활동은 궁극적으로 안살림을 지원하는 차원에서 이루어졌다.

조선시대의 집안 살림은 크게 안살림과 바깥살림으로 나뉘어져 있었다. 음식 장만과 옷 짓기 등의 안살림은 주로 여성들이 담당하고, 각종 생계활동이나 재산증식, 살림살이, 노비관리 등 바깥살림은 주로 남성들이 담당했다. 또한 남성들은 정원 가꾸기, 자식교육, 가족 돌보기 등 정서적 활동에도 참여했다.

여성들이 안살림에 전념할 수밖에 없었던 것은 이 일들이 가족의 생존과 직결된 필수 노동임과 동시에 작업 과정에 긴 시간이 소요됐기 때문이다. 길쌈은 가족들이 입을 옷을 짓는 일이기도 하였으나 이를 통해 각종 세금을 납부하거나 화폐로도 사용되었기 때문에 집안의 생계가 걸려있었다. 또한 밥 한 그릇만 지으려 해도 방아를 찧고 불을 때야 하는 통에 꼬박 한나절이 걸렸다. 게다가 여성들은 자신의 목숨을 담보로 임신과 출산을 하였으니 남성들에 비해 여러 가지 살림을 해낼 수 없었다.

다만 조선시대에는 남녀간 성별 역할이 나뉘거나 고정화 되어있지 않았기 때문에 상황에 따라 상대방의 역할을 담당하기도 했다. 예를 들어 16세기 송덕봉은 남편인 미암 유희춘이 유배나 관직생활 등의 이유로 집을 자주 비우자 혼자서 안팎의 살림을 모두 주관하였으며 18세기 연암 박지원은 아내가 먼저 세상을 떠나자 자식 교육과 음식 수발, 가족 돌보기 등 아내의 역할까지 도맡아 하였다.

남자가 살림하는 건 부끄러운 일이다?

조선 후기에 최상층 가문 출신만이 관직에 오를 수 있다는 ‘문벌사회’가 도래하였다. 그 결과 애초부터 관직에서 탈락된 양반, 즉 몰락 양반층이 날이 갈수록 늘어났다. 이들 몰락 양반은 좋게 말하면 글공부에 전념하고 나쁘게 말하면 놀고 먹으면서 집안 살림을 돌보지 않았다. 그래야만 가문과 양반 신분을 유지할 수 있었기 때문이다. 만약 생업에 뛰어들면 그들 역시 평민들처럼 군역이나 부역을 져야 하고, 혼벌(婚閥)조차 떨어지기 때문이었다.

더불어 조선 사회에 성리학이 정착하고 내외법이 강화되면서 남성들의 살림에 대한 사회적 인식이 달라지기 시작했다. 남성들이 살림에 참여하는 것을 부끄럽고 창피한 일로 여긴 것이다. 이러한 영향으로 남성들이 집안 살림을 등한시하자 자연히 여성들의 역할이 늘어날 수밖에 없었다. 안살림뿐만 아니라 남성들의 바깥살림, 특히 다양한 생계활동과 재산증식 같은 경제적 책임까지 떠맡아야 했다.

그렇다고 조선후기 남성들이 일체 집안 살림에 관여하지 않은 것은 아니었다. 당시에도 집안의 규모가 워낙 크고 해야 할 일이 많았기 때문에 남녀가 동업(同業)하지 않고서는 존립 자체가 불가능했다. 다만 사회적 분위기로 인해 겉으로 드러내지 못했을 뿐이다. 이는 여성의 창조활동을 통한 사회 참여를 금기시하는 사회적 분위기로 인해, 조선후기 여성들이 남몰래 작품을 쓰거나 혹은 무기명으로 작품을 발표했던 것과 같은 이치였다.

아주 최근에 형성된 ‘가부장제’

그렇다면 남성들이 집 밖의 일터에서 오로지 경제활동에만 종사하게 된 것은 언제부터였을까? 요즘 우리가 겪고 있는 성별 역할구분의 가부장제는 비교적 최근인 일제강점기와 산업화 시대에 본격적으로 형성된 것이었다. 그것도 내재적, 자발적이 아닌 식민지와 전쟁, 자본주의 산업화라는 외재적, 타의적으로 주입된 것이었다.

일제의 식민지적 근대화를 겪으면서 우리나라도 집안보다 사회의 비중이 커지기 시작했다. 사회와 집안은 공(公)과 사(私)로 구분되고, 집안은 철저한 사적 영역으로 치부되었다. 그와 함께 사회는 남성의 영역으로, 집안은 여성의 영역으로 각각 역할을 부여 받았다. 조선 시대만 해도 남녀의 역할 구분은 상황에 따라 유동적이었으나 일제의 식민지 시기에 이르러 성별에 따른 역할 구분, 곧 남녀의 이분화가 이루어진 것이다. 이제 남성은 사회에 나가 경제활동만 담당하면 되었고, 여성은 가정에 남아 전업 주부로서 가사를 담당함은 물론 자녀를 양육해야 했다.

또한 1970년대 이후 현대의 자본주의적 산업화는 사회와 가정을 더욱 분리시키고, 남성과 여성의 성별 노동 분업을 강화시켰다. 게다가 이제 여성은 집안일 뿐 아니라 ‘사랑’이라는 정서적 역할까지 부여 받았다. 사랑과 정성으로 남편을 비롯한 자식들을 뒷바라지해야 한다는 것이었다. 이로써 남성은 생산자, 여성은 소비자라는 인식이 널리 확산되었으며, 가정은 소비공간이자 휴식공간으로 낮게 평가 받게 되었다.

결국 현재 우리가 겪고 있는 남녀의 이분법적이고 성별 역할 구분이 뚜렷한 그야말로 왜곡된 가부장제는 조선 시대가 아닌, 일제강점기와 현대 산업사회라는 아주 최근에 형성된 것이었다고 보아야 할 것이다.

현대는 지식노동의 사회이자 성 평등 사회로, 여성의 사회참여의 비율이 날이 갈수록 커지고 있다. 이젠 한국 사회도 남녀 모두가 자유롭고 공평하게 사회활동과 집안 살림에 참여할 수 있어야 한다. 여성의 일과 가정의 양립도 중요하지만, 남성의 일과 가정의 양립 역시 매우 중요하다. 조선시대 남성들도 그 많은 집안 살림에 참여하면서도 얼마든지 자신과 나라를 위해 일하지 않았던가.

Text by 정창권, 고려대학교 문화창의학부 조교수

Illustration by 유환영