Feature

Emperor Gojong, a Visionary Leader

By Yi Tae-jin

Attempting to appeal to the international community about the illegality of ‘the 1905 Protectorate’ forced by Japan, a coerced treaty that had never been ratified by Gojong, Emperor Gojong dispatched three emissaries to the Hague Peace Conference in 1907. They were Yi Sang-seol, Yi Jun, and Yi Wi-jong. Although they were denied entry in the face of Japan’s diplomatic obstruction, Yi Wi-jong held a press conference with the help of the English journalist Willam Stead.

He, speaking in French, gave a detailed explanation of Japan’s diplomatic maneuvers to illegally take control of Korea, attracting a great deal of attention from the international community. Yi Wi-jong, along with Yi Sang-seol, also did an interview with the American newspaper New York Times. A photograph of the 1907 Hague Peace Conference from an August 1907 issue of the French weekly newspaper L’illustration (photo courtesy of the National Palace Museum of Korea)

King Gojong (r. 1863–1907), the 26th ruler of the Joseon Dynasty, declared the Daehan Empire (“Korean Empire”) and proclaimed himself its Emperor in October 1897. He became the commander-in-chief of the country’s armed forces and promulgated Korea’s first modern constitution, known as the Daehanguk Gukje. He spearheaded the establishment of a public medical school, a public educational institution for training in medical skills, and disseminated guidance on the prevention of infectious disease. He sent talented young Koreans overseas to study and set up institutions specializing in education on commerce and industry. He also established a bank called Hanseong Bank. All of these measures reflect this unlucky ruler’s lofty dreams of transforming Korea into a modern state. (Editor’s Note)

An Undeserved Nickname

The final king and first emperor of Korea, Gojong’s name was commonly appended with a derogatory modifier meaning “foolish.” Japanese journalists had called him gifted with the skills needed by a good monarch before Korea was forced to sign the Korea-Japan Treaty of 1905 (Eulsa Treaty). The tone of their writing took a sudden turn when Gojong secretly dispatched emissaries to the Hague Peace Conference in 1907 in protest of Japan’s forceful imposition of the 1905 treaty on Korea. Afterwards, this monarch formerly considered well-qualified obtained the nickname “monarch in the dark” in their writings, which transformed into the more common description “foolish monarch.” However, this “foolish monarch” was seen from a different light by Western journalists.

Their views of Gojong are expressed in The Korean Repository, a monthly English magazine launched in 1892 by Western missionaries, advisors, and diplomats who were active in Korea at the time. In commemoration of the first anniversary of Empress Myeongseong’s assassination by Japanese agents in October 8, 1895, two journalists from The Korean Repository, Homer Hulbert and Henry Appenzeller, conducted an interview with the mourning Gojong and ran it in the November 1896 issue. Their copy is entirely favorable to him. It reads: “Toleration in religious matters has marked the reign of His Majesty. ... On the contrary [to his father Daewongun], ... the King has given distinct and direct encouragement to missionaries, or he terms them, ‘teachers’. And on the occasion of an audience accorded to Bishop Ninde of the Methodist Episcopal Church, in the beginning of 1895, His Majesty not only expressed his appreciation of the good work done by them, and thanks for the same, but spoke those memorable words which the churches cannot and must not forget, ‘Send more teachers’. The disposition of the King is kindly and amiable.”

Gojong is also described in The Korean Repository as the nation’s foremost intellectual. The magazine recounted that he possessed a large collection of books in his library and was surrounded by knowledgeable courtiers engaged in constant discussion. After presenting a few anecdotes about him, the article relates that although complaints about ministers and officials ran high among the people, no one pointed any blame at the king.

According to The Annals of Emperor Gojong, he is said to have rejected a proposal by one of his courtiers to suppress the Donghak (“Eastern Learning”) Peasant Revolution in 1894, retorting that followers of Donghak were also his subjects and it was nonsensical to crack down on them. This comment delivers the profound love he felt toward his subjects. Regarding the violent suppression of this social and academic movement supported by farmers and Donghak believers, a new hypothesis has been recently proposed by some Japanese scholars. Their studies argue that it was Japanese deception that triggered the crackdown on the Donghak Peasant Revolution.

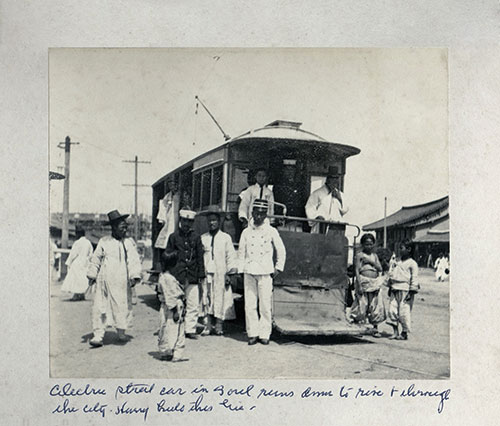

Gojong established the Hanseong Electric Company with technical assistance

from the Collbran-Bostwick Development Company, introducing streetcars to Seoul in 1899,

three years before Tokyo (photo courtesy of the Korea Electric Power Corporation).

Toward a Nation State

Gojong published a doctrine called Hongbeom Sipsajo (“14 Great Rules”) on January 8, 1895, declaring, among other reforms, the precedence of merit over social status in hiring. Following this policy document laying down principles for social reform, royal edicts directed at the public were issued in the Korean alphabet with only some Chinese characters, not in Chinese as previously was the custom. He unveiled principles for the reform of education through the promulgation of the Education Prescription (Gyoyuk Joseo) on February 2, 1895, emphasizing the need for universal education as part of nation-building efforts. Enshrined within the Education Prescription is a three-pronged focus on intellectual knowledge, moral ethics, and physical health. A teacher’s college was established to train qualified teaching staff, and institutions for primary education were established to the greatest degree possible. The Independence Club (Dongnip Hyeophoe) was launched as a public-private cooperative venture aiming at modernization. The club’s newspaper, The Independence (Dongnip Sinmun), was published in Korean. Western-style songs began to be composed and popularly enjoyed. Among them were a national anthem and school songs that fueled a sense of patriotism among the Korean people.

Against this backdrop of gradual steps toward reform and modernization was born the Daehan Empire in October 1897. The long-standing name Joseon had been subject to the approval of the emperor of China and was therefore not fitting for a new era that pinned its hopes on independence. Daehan, or “Great Han,” was proposed by Gojong and selected as the new title with the consent of an absolute majority of his ministers.

A Bold Attempt at Global Peace

Gojong sent a congratulatory embassy to the coronation of Nicholas II of Russia in April 1896. Min Yeong-hwan, the head of the diplomatic mission, was actually pursuing a secret mission from Gojong to negotiate a loan from the Russian government. This was part of Gojong’s national plan to borrow capital from Western powers and conduct modernization programs while acquiring international recognition as a neutral country. With the help of Russia, corporations from France and Belgium expressed their intention to invest in Korea. Gojong worked to meet the conditions required for becoming a neutral country—joining the Universal Postal Union and Red Cross and becoming a signatory to the Hague Conventions.

The Japanese legation in Korea noted Korea’s aspirations and took steps to obstruct them. The first Anglo-Japanese Alliance, signed in January 1902, prescribed that the political, commercial, and industrial interests of Japan be protected in Korea. This was an obvious expression of Japan’s intention to block Korean attempts to secure foreign loans and achieve political neutrality. Upon the unveiling of this alliance with Britain, the era’s major player in international finance, the interested French and Belgian corporations withdrew their pledges for investment in Korea. Japan also pulled the United States to its side by promising the newly-elected President Roosevelt that it would wage war on Russia. As the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 ended in a victory for Japan, the Daehan Empire saw its fate imperiled.

When Gojong’s dispatch of envoys to the Hague Peace Conference in 1907 was revealed, he was forced to abdicate in favor of his son. In this same year a nationwide campaign was undertaken by the Korean public to pay back the enormous debt owed to Japan through individual donations. They pursued this debt redemption campaign in the belief that it was a public duty to participate in eliminating national debt. It signified the birth of a nation state driven by the active performance of public duties.

In a royal edict issued in March 1909, Gojong declared, “Daehan does not belong to me, but to all of you.” Even after Korea officially became a colony of Japan after the former was forced to sign the Annexation Treaty in 1910, Koreans, emboldened by Gojong’s declaration, did not halt their efforts for independence. They supported the organization of independence activist groups at home and abroad and assisted the formation of armed forces as fighters for national independence. Gojong died in March 1919, long before the eventual achievement of liberation in 1945.

However, his funeral offered an occasion for the launch of a national independence drive, or the March 1 Movement. A nationwide expression of resistance against Japan and of aspirations for peaceful coexistence, the March 1 Movement is an informative example of peace movements around the globe. It would not have been possible without the sense of community that brought Koreans together as the people of one nation state, or the Daehan Empire.

Text by Yi Tae-jin, Honorary Professor, Seoul National University

Photos by the National Palace Museum of Korea and the Korea Electric Power Corporation

대한제국이 꿈꾼 나라

임금은 ‘황제’가 되었다. 황제는 육해군을 직접 통솔하고, 최초의 헌법인 대한국제를 반포했다. 통화를 개편하고 한성은행 등 금융기관을 설립했다. 의사 양성을 위해 경성의학교를 설립하고 전염병 예방규칙 등을 배포했다. 해외에 유학생을 파견하여 근대산업기술을 습득케 하고, 기술자와 경영인 양성을 위한 실업학교를 만들었다. 근대국가로의 발전을 위한 이 행보, 1897년 10월, 대한제국 선포로 하여금 이루어진 일들이다.

오명에 가려진 왕, 고종

고종에게는 바보 군주란 오명이 붙어 있다. 1905년 11월 ‘보호조약’ 강제 이전에 서울에서 활동하던 일본 신문 기자들은 조선 군주는 군주의 자질이 있다고 평했다. 고종이 조약 강제를 한사코 반대하고, 1년 반 뒤 헤이그 만국평화회의에 3특사를 보내 일본의 불법을 폭로한 것을 계기로, 일본 기자들의 논조는 달라졌다. 한국 황제를 ‘암군(暗君)’으로 부르기 시작했고, 이는 바보 군주라는 말로 바뀌었다. 그러나 고종을 평가하는 서양 기자들의 시선은 달랐다.

1892년 서울에서 영문 월간 잡지 『한국지식보고(The Korean Repository)』가 발행되었다. 조선에서 활동하던 서양 선교사, 고문, 외교관들이 한국의 역사와 문화를 세계에 알리기 위해 만든 잡지이다. 1895년 10월 8일 왕비가 일본인들에게 살해당하는 사건이 발생하고, 이듬해 1주기를 맞아 이 잡지의 두 기자인 호머 헐버트와 헨리 아펜젤러가 상중의 고종을 인터뷰 했다.

기사는 시종 호의적이다. ‘고종은 외국인들을 궁으로 초대하면 입구에서부터 한 사람씩 안부를 물을 정도로 자상하다. 아버지 대원군과는 달리 종교, 특히 기독교에 매우 관대하다. 수개월 전, 남 감리교 주교(닌드)가 알현하는 자리에서 임금은, 선교사들은 우리에게 신문명을 가르쳐 주는 선생님들이니 더 많은 선생을 보내 달라고 부탁했다고 전했다. 교회로서는 잊을 수 없는, 절대로 잊지 말아야 할 말씀이다.’

이 잡지는 또 고종이 나라 안에서 최고의 지식인이라고 소개하였다. 서재에 많은 책이 있고, 학식 많은 신하 몇이 늘 여기서 근무하며 고종과 대화를 나눈다고 하였다. 이런저런 일화 소개 끝에 백성들은 대신이나 관리들에 대한 불만, 불평은 많아도 임금을 탓하는 사람은 아무도 없다고 하였다.

1893년 동학 농민군을 토벌할 것을 건의한 한 신하에게 ‘동학 교도 역시 나의 백성인데 어찌 그들을 토벌한다는 말인가’라고 건넨 고종의 말에 그가 얼마나 백성을 사랑하고 있는지 담겨있다. 최근 동학 농민군을 토벌한 것은 일본군 측의 위계로 이루어졌다는 새로운 연구가 나오고 있다. ‘양심적인’ 일본 역사학자들이 내놓은 문제 제기이다.

국민 국가로 가기 위한 길, ‘대한제국’ 선포

1895년 1월 8일, 고종은 한국 최초의 근대적 정책백서인 ‘홍범 14조’를 고하였다. 앞으로 인재 등용은 양반 여부를 따지지 않는다고 선언했다. 이때부터 백성들에게 내리는 교서는 한문이 아니라 국한문혼용체로 바꾸었다. ‘교육에 관한 교서’를 통해 평민이 나라의 주인이 될 수 있도록 교육을 새롭게 한다는 방침을 밝혔다. ‘교육 교서’는 놀랍게도 지, 덕. 체 3양(養) 교육을 제창하였다. 또한 한성사범학교를 세워 교사를 양성하고 소학교를 힘닿는 대로 설립하였다. 사회 각계가 근대화에 나서도록 관민 협동 조직으로 독립협회를 발족시켰다. 협회의 기관지 ‘독닙신문’은 순 한글로 발행하였다. 공식 국어가 국한문 혼용으로 바뀌면서 서양식 노래를 지어 부를 수 있는 뜻밖의 효과가 생겼다. 우리말로 애국가, 교가 등을 지어 부르면서 애국심을 고취하였다.

이런 변혁 위에 1897년 10월 ‘대한제국’이 탄생하였다. 5백 년간 쓴 조선이란 국호는 아름답지만, 태조가 처음 나라를 세울 때 명나라 천자의 승인을 받아 사용한 것이므로, 자주 독립국 시대에 어울리지 않으니 우리를 가리키는 다른 호칭 한(韓)을 택하여 ‘대한제국’으로 하자고 제안하였다. 고종이 스스로 지어 절대 다수의 찬동을 받아 결정한 새 국호였다.

대한제국, 국제 평화를 향한 신호탄

고종은 1896년 4월 니콜라이 2세 러시아 황제 대관식에 민영환을 축하 사절로 보냈다. 특명전권공사 민영환은 러시아 정부를 상대로 차관을 교섭하라는 밀명을 받고 있었다. 고종은 서구 열강의 자본을 들여와 산업을 개발하면서 중립국으로 인정받는 국책을 세웠다. 러시아의 주선으로 프랑스와 벨기에 기업들이 투자를 희망하였다. 1900년부터는 중립국 기본 조건으로 국제우편연맹, 적십자사에 가입하고 1903년에는 헤이그 만국평화회의 회원국이 되었다.

주한 일본공사관은 이를 탐지하여 방해하기 시작하였다. 1902년 1월 말 발표된 ‘제1차 영일동맹’은 영국은 한국에서의 일본의 정치적, 상업적, 공업적 이익을 보장한다고 규정하였다. 누가 보아도 대한제국의 차관도입과 중립국화 정책 저지를 겨냥한 것이었다. 영국은 당시 국제 금융을 좌지우지하는 나라였으므로 조약이 공개되자 프랑스, 벨기에 기업가들이 물러섰다. 일본은 청일전쟁 때, 미국이 조선 편을 든 것을 잊지 않고 새로 부임한 시어도어 루스벨트 대통령에게 러시아와의 일전을 약속하면서 일본 편을 만들었다. 1904년 러일전쟁이 일본의 승리로 돌아가자 대한제국의 운명은 풍전등화가 되었다.

고종은 1907년 헤이그 특사 사건으로 강제로 퇴위 당하였다. 같은 시기 국민들 사이에서 일본이 외국으로부터 끌어온 나랏빚을 갚자는 ‘국채보상운동’이 일어났다. 모두 나랏빚을 갚는 것은 국민의 의무라고 외쳤다. 의무를 앞세운 국민 탄생, 세계 역사상 유례가 없다.

고종은 1909년 3월, “대한은 나 한 사람의 것이 아니라 여러분 만성(萬姓)의 것이다”라고 선언했다. 국민들은 1910년 강제 병합 속에서도 국내외에 독립운동 단체를 조직하여 항일운동을 꾀했고, 국군인 의군(義軍)을 조직하며 나라의 독립을 위해 맹렬히 싸웠다. 1919년 3월, 나라의 독립을 보지 못한 채 고종이 승하했다. 고종의 국장을 계기로 일어난 독립만세 운동은 전국민 항일운동이자 평화 공존 운동으로, 20세기 국제 평화 운동 선두에 서 있었다. 대한제국의 국민이라는 의식이 없었다면 결코 일어나지 않았을 결과다.

Text by 이태진, 서울대 명예교수

Photos by 국립고궁박물관, 한국전력공사